As the theater shook with the shouts and crashes of the brutal action sequences, my parents and I sat in taut silence, broken only by the occasional crunch of popcorn and slurping of an extra-large Coca-Cola. The audience was entranced, eyes glued to the screen, even when the protagonist broke his leg with an all-too-sickening crunch. But unlike the twenty other people in the room, I wasn’t lost in this fantasy world of war and violence. I wasn’t listening to tense whispers shared between allied soldiers or the ripping shouts and curses of the tortured prisoner. I was reading the subtitles, the little white English words, popping up as the staccato of Korean rushed right by my ears.

Words, once familiar friends but now complete strangers, taunted me as they swam in a whirlpool of lines and characters, confusing sound for sound until they all lost meaning. My native language, the first words I ever spoke—omma—my mother tongue, now a foreign entity, an unwelcome invader. My childhood ignorance, my youthful naivete, and most importantly, my effortless ability to learn were all gone, leaving me with nothing but the bitter awareness of past folly.

I used to be immersed in Korean—from the hospital on the other side of the Pacific where I was born to the lessons I took at my church every Sunday after service. The words surrounded me, offering themselves at no cost. Sitting at my desk every week, folding my legs into a pretzel as I waited on my tiny red plastic chair, counting down the seconds until the teacher dismissed us for the day, I hated every moment of Korean school—the teacher that never called on me, everyone else who seemed to care so much more than me, that I was being forced to learn this stupid, useless language.

Now, the language I shunned with childish impudence comes back to slight me. When I sit down at a restaurant with my parents, the menu reads as if written in hieroglyphics, an ancient language destined to be decoded only by those with a secret key, a key that I once saw but never mastered. Daunted by the challenge of translating everything, I hand back the menu, resigned to let my father order for me once more.

As I slurp down my dish of vermicelli noodles, coated in a rich bone broth, I don't taste the love and experience of the skilled hands in the kitchen, nor the hours of labor that went into creating that luxurious soup, nor the multitude of foreign—yet familiar—spices and flavors; no, I only taste failure. Everything I see, from the plethora of dishes on cheap, plastic tablecloth, to my distorted reflection in the curved surface of the spoon, is visibly Korean. The flavors and smells of the dishes in front of me can be mistaken for nothing but. My neighborhood, containing the largest concentration of ethnic Koreans outside of the motherland, could be mistaken for Seoul itself with its neon signs emblazoned with Hangul characters. Every noise, from the relentless chatter of school-aged children to the strident voices of ahjummas, is distinctively Korean. Korea does not just surround—it overwhelms.

Despite its unrelenting presence, Korean remains unreachable, an intangible entity that continues to tease me. Within it is the promise of the past, the connection to a family and cultural history that threatens to fade every day. The aging of my grandparents and my parents looms over me, transforming the promise of Korean into a threat. Every day that passes seems another day lost to monolingualism, and with it, an entire history.

The prospect of never speaking to my parents in their native tongue tortures me, creating the haunting idea that I’ll never truly connect to my past. My grandmother calls from Korea every weekend, and I used to run upstairs, terrified that she would ask for me. Now, I volunteer to answer the phone, excited to have the opportunity to practice with someone even if the conversation remains stilted and uncomfortable. The words, still unfamiliar to my ears and unnatural on my tongue, flow out more easily than I expected, coming out from the secret reserves where my mind has been hiding them for years.

The battle wages as dueling forces, cultures, and lives square up within me. My tongue, once a traitor, yields to the soft-spoken syllables of Korean. Battlefields become learning zones as effort unlocks the once-impenetrable secrets. I rediscover this unattainable key, finding it to be much closer to home than I thought.

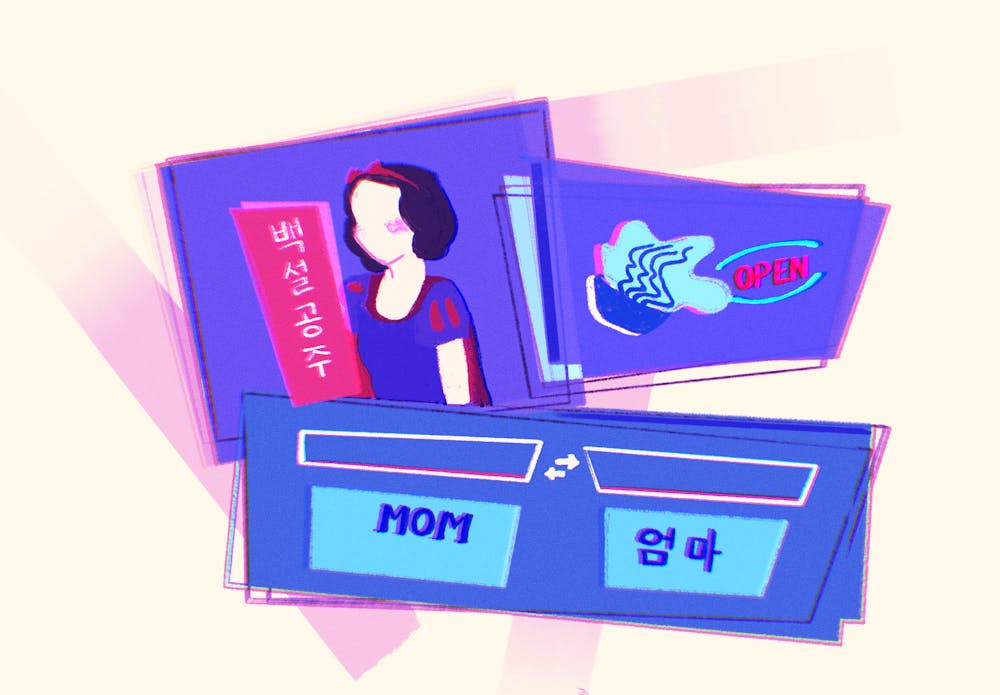

After a week of living our separate lives, my family always joins together on Sundays for movie night, a chance for us to reconnect and forget about the worries of the week. This time, it is my turn to choose, so I pick the movie that was my favorite as a child: Snow White, but on a Korean DVD. I am transported to my childhood land of witches and dwarves, of magic and music, but when the singing of the birds and princess gets too fast to understand, I turn to the subtitles for clarity—for character, for language.