One year, my mother committed herself to scrapbooking my oma’s life. For weeks, she scoured the depths of old boxes and dusty albums, until she’d found records of every pivotal moment of my oma that she could. Sepia, water-stained photos adorned the pages, accompanied by careful captions, dates.

When presented with the gift, my oma pointed at her own wedding photo—at herself, in that charming white gown—and asked who the lovely woman was.

In some ways, I envied it. We age our entire lives, grow bigger, wiser, stronger—and then, inevitably, we return to infantility. Returning, finally, to that peace known only in youth.

Often, I crave that innocence, but the trade-off is too much to bear.

*

During one dementia-fueled haze, my great-grandmother started speaking to us in Dutch.

It had been well over seventy years since the Dutch occupation. Indonesian had been her everyday language for decades. But as my oma inched past 90, the Dutch words rolled off her tongue. Foreign, but ingrained.

Unable to engage, my family simply let the episode pass.

Modern medicine is one of life’s greatest blessings. I have no doubt that, without it, natural selection would have weeded my family out long, long ago. Knobby knees, the worst spines, a myriad of cancers—but, of everything that runs in my family, whatever brought on my oma’s dementia is certainly the worst.

Aging is cruel enough in good health. To love, be loved, to lose. To grieve yourself before you are even gone. Crueler, though, is to lose yourself, and not even realize.

In her last days, my oma did not know how to love; she had forgotten everything she needed to know to be able to. Names, feelings, words. Still, we stroked her hair, washed her back, and watched her fall apart before us, whispering gibberish, speaking in tongues. We loved her so dearly—and she could not know it or return it, seeing us only as strangers.

I don’t think her dementia was ever explained to me. Would it have hurt less if it was? If I understood why she had forgotten me, after all the love she’d shown me?

I grieved her with every breath she took.

*

I cannot bear the thought of forgetting. The fear consumes me, pounding at the forefront of my mind, throbbing at my fingertips for something to be done.

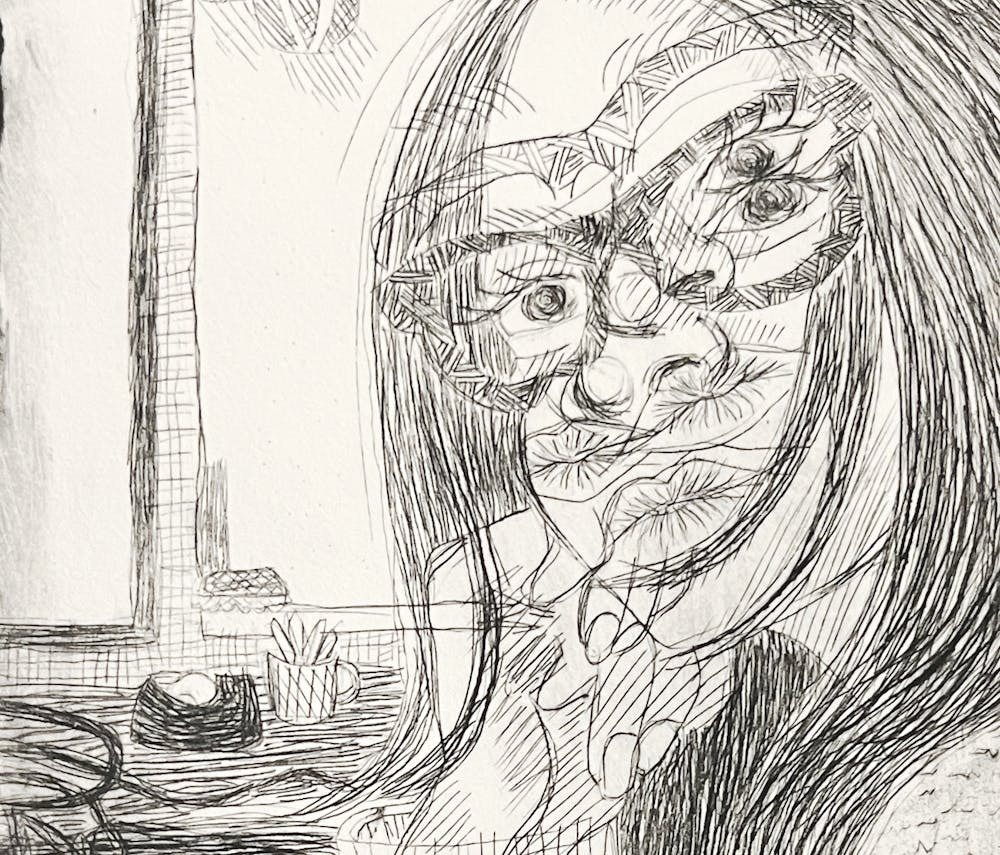

I cannot help but return to writing, not because I enjoy it, but because I cannot exist without it. I scrawl the dates in, underline the hours. I journal obsessively; my writings trap the ephemeral in an uneasy dance with time, willing fluid moments still.

I study history, fueled by this same fear. A history major promises neither riches nor recognition. But I return nonetheless, unable to leave it behind. I fear, without it, my people’s realities and truths will cease to exist. That, one day, my culture and world as I know it will simply be lost.

I was not told, in my childhood, the stories of my country’s past. My family avoided the topic in the same way my teachers did—but I heard whispers.

Did you know?

My dad was saying…

Hushed voices. The naive, childhood gossip in the backs of classrooms, describing a flight from repression; the fear of death, of crossing invisible lines. Of power, abuse, and atrocities committed in the supposed defense of a freedom we still do not know.

So much of our history has been silenced, its events existing only in the fragile minds of a few. The government, the elite—they prefer it this way. A history that remains only in memory will be forgotten. Sins, fading with time.

I want to jot it down, this truth; the memories of my people, before they are gone. Recording it all is an impossible task. But still I try, fervently, exhaustively.

Foolishly.

I hope my efforts will be enough.

*

Academics gather knowledge obsessively, for what are they without it? Botanists, archaeologists, anthropologists, historians. In search of some higher knowledge, they seek out ‘foreign’ lands, searching for something to bring home. With just the rudiments of local languages, the white man has pressed native communities for all they are worth: Resources. Geography. Know-how.

We’ve been raised to value these findings, to respect science, history and the arts. Intelligence, they tell us, lies here; in the language of the white man. But the foundation of our knowledge systems is inherently linked to a culture and history of exploitation. To the white man, we were not fellow humans, full of emotion and breath, but a mere trophy on their walls; something to conquer, not love.

Academia does not serve the interests of those it depicts. The colonial archival urge did not exist to honor our cultures, but to document us as ‘others’; to identify points for exploitation. Even today, indigenous history around the world is controlled, primarily, by those with power. The systems in place have ensured it.

In a field where my people have been silenced for so long, I want to be their voice. If knowledge is power, then do we not deserve to wield it for ourselves? To fight back against these narratives?

I often dwell on what it means to preserve the present; to archive the past. I cannot bear losing the stories of my people. I return, always, to this urge of mine to document, this fear of loss and forgetting. But how can I do this, knowing all the wrong that has come before me? Is what I am doing any different at all? Am I not just a pawn, a cog in these very same institutions, upholding the colonial ideals as the ravaging white men before me?

I can only hope that my ancestors will forgive me.

*

“Without forgetting, nothing would work.” Oliver Hardt of McGill University said this of memory. The sentiment is both poetic and biological. Life is a cycle of remembrance and loss. To make room for more, something must go.

Forgetting is hard in the same way that loss is hard, and we are powerless to stop them both. To capture the human experience in its entirety is futile—and god, have I tried. I have hashed through every medium, every possible method I can. And with each one, I fail.

No piece of mine will ever replicate the sound of a loved one’s voice. A video might—but never in the way I heard it first. I will never collect the bite of a first snow, the callouses on an old friend’s hands. I cannot tell you what it feels like to be struck, to strike, to feel the sting of a tired, weary palm.

I will never know the aches of another, in the same way you will never know mine. And, even then, I will forget. I will forget the folds of my oma’s skin, the crinkles of her smile, the fear in her eyes. I will forget what it meant to sit by her, to hold her hand, to shut my eyes, willing it all to last.

Only the present is guaranteed, and the knowledge of an end only makes me cherish it more.

*

By the time my oma passed away, there was nothing left to grieve. For years, she’d been a shell of the woman she was in her youth, feisty sparks long snubbed by life, loss. I had grieved her all my life, and now it was done.

It should not have hurt to see her go. She did her time, and she did it well, and life had dealt enough suffering to her that to die was not a condemnation, but an offering of peace. A chance, finally, at solace.

But still, I wept, overcome with a sense of finality I’d come to dread.

My oma left with knowledge we will never recover; with the history of my people, of my family, of herself.

But I remember her, and I will make that enough.