I sat in my dorm’s communal kitchen painting my friend’s nails. It was mid-first semester and the heat hadn’t turned on yet, so it was uncomfortable to wear anything less than a sweatshirt. Every time I finished a nail, my friend would lift his hand close to his eyes to examine the quality of my application, then, once satisfied, continue scrolling on TikTok with his fingers fanned out in fear of smearing nail polish across the screen. Between his fingers I caught glimpses of random clips and the words “#fyp #corecore #nichetok.” Piano music and the ambient sounds of Beach House and Aphex Twin reverberated through the tiled walls.

Over the last five years, adding -core to words has gained popularity to denote a certain style or aesthetic. Cottagecore, fairycore, glitchcore, and a bottomless pit of other -cores provide niche descriptions of clothing, music, and Pinterest photos. Out of the fire of -cores rose a phoenix: corecore. Characterized by rapid-moving videos and images, often repeatedly slapped on top of each other, corecore began as a response to diluted internet memes—a counterculture that at least differentiated itself from mindless content and at most raised support for political movements. Corecore videos with clips of the Arctic and pollution formed moving collages of environmentalist messages. By compiling media from a variety of sources, corecore creators like Mason Noel and High Enquiries on TikTok visualized the issues happening in the world, garnering support through concrete evidence and individualistic medleys. However, with the growth of corecore and its expansion outside of a political or philosophical sphere, corecore lost its ethos.

Over time, corecore came to be comprised almost completely of abrupt transitions between meaningless clips, Ryan Gosling in Drive, Ryan Gosling in Blade Runner 2049, and Ryan Gosling in La La Land (sensing a pattern?) backed by emotional music and dialogue without context. Corecore became an aesthetic rooted in aesthetics.

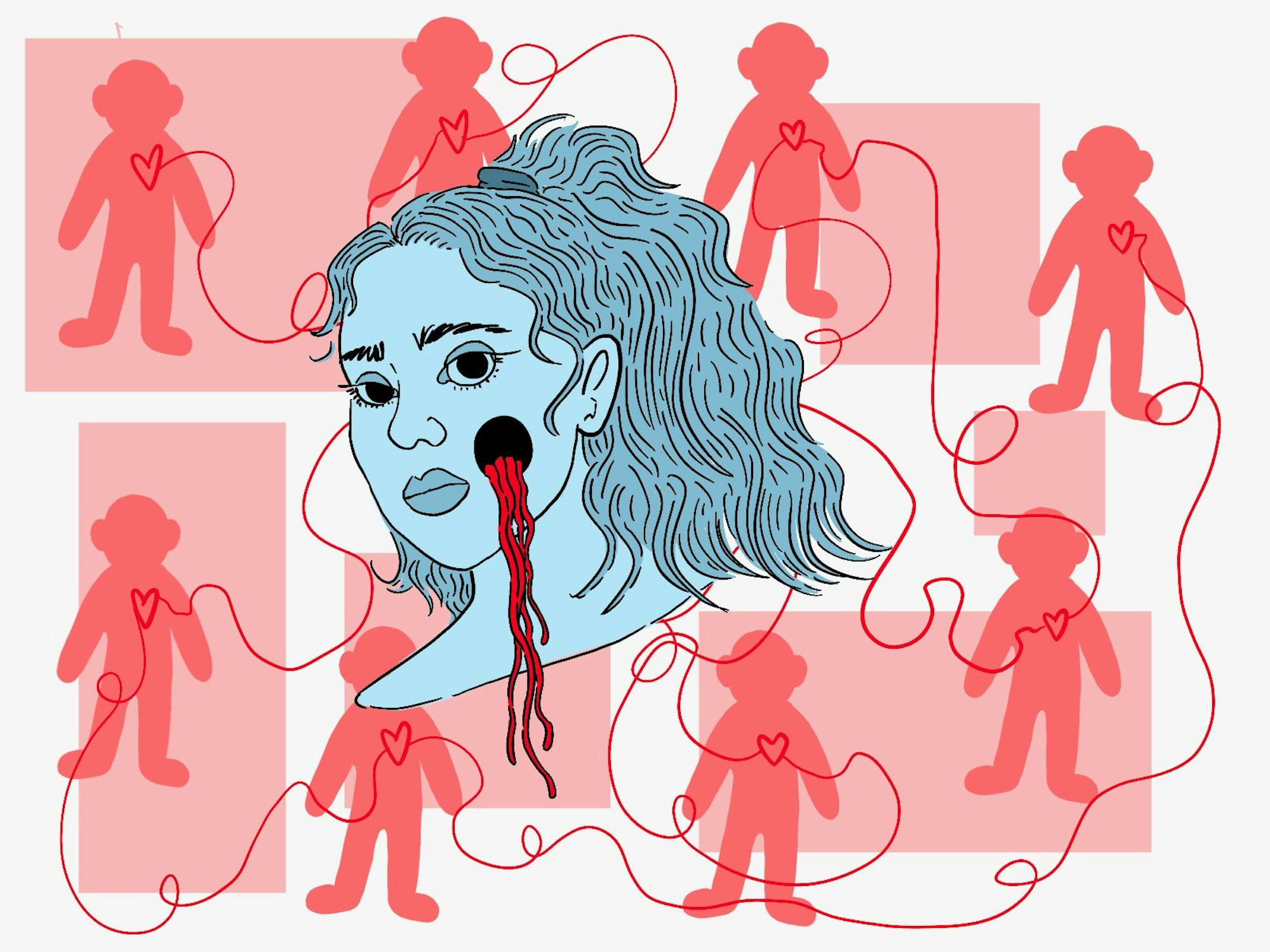

Corecore grew in popularity because it evokes emotion. With no time to dwell on one clip before you’re shown the next, corecore creators rely on immediate visceral reactions for virality. Thus, they must appeal to strong human emotions: love, joy, and most notably, sorrow, which, with depression rates rising, is an easy way to appeal to young audiences. In a study of depression rates between 2015 and 2020 published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine, depression prevalence rates have increased by 4.2% and 6.9% for those aged 12–17 and 18–25 years, respectively. Another study in the Journal of Adolescent Medicine comparing undergraduate students in 2011 and 2018 found that rates of severe depression, suicide ideation, self-harm, and suicide attempts dramatically increased in this period. Intense sorrow is almost a given in a generation that only grows sadder, but an aesthetic defined by nothing but its aestheticism naturally finds its M.O. in glamorization. Portraying sorrow as it comes is boring. No one wants to see the rawness of unbrushed teeth and moldy cups—they want to see it filtered and dressed up. Thus, corecore edits find easy success in depicting sorrow, and more importantly, by romanticizing it.

There’s no shortage of wallowing online, especially among young people. Recommendations begin with “[insert X product] for sad girls,” with Lana Del Rey playing in the background. Young boys comment “real” and “he just like me fr” on videos of Donnie Darko and Tyler Durden. Creators depict pain as something beautiful, whether through photo dumps of smudged mascara and lipstick stains or Hans Zimmer soundtracks. Not only do they find the beauty in life while suffering, but they depict suffering itself as beautiful. To romanticize sorrow, however, is to perform. It is to split the mind in two: the agent and the viewer. It is to reduce life to a sight. In a culture that values aesthetics and with an algorithm that actively rewards it, it’s easy to wade in sorrow. Melancholy becomes more than a feeling or a state of mind—it becomes a state of being.

I was a sophomore in high school looking up protein powder on Amazon on my mom’s computer. I woke up early, bathed in dry shampoo, and pretended that the neatness of my notes made up for the heaps of clothing on my floor. My teachers described me as responsible and driven while I wondered how much longer I could contribute to a discussion on a book I didn’t read. I did my algebra homework from three weeks prior by a west-facing window so the sunset would cast a golden light across the page.

What I perceived to be “having my life together” was nothing more than a superficial attempt for order because that was all I had been exposed to. All I saw on the internet were white, cishet, thin women promoting yoga and pilates, matcha lattes and green smoothies, Gigi Hadid’s pasta recipe and air fryers. Overall, it was nothing more than a hyper-capitalist echo chamber that bred consumerism over true remedies. This isn’t readily visible to the public because all viewers see is a video of a conventionally beautiful woman getting ready in a cacophony of creams and beiges with a voiceover that preaches “romanticizing your life.”

Pretending life is a movie will not necessarily make it any better. Feigning wellness and romanticizing sorrow do not genuinely improve wellbeing. Instead, they yield perfectionism and scrutiny of the self. Life shouldn’t always be beautiful, and actions do not need to have aesthetic value to be valuable at all. Math homework does not need to be done in pretty lighting to be worth doing.

Furthermore, romanticizing life relies on luxury and privilege. The same women who promote wellness culture and romanticizing life post photos of cabinets full of skincare products and their personal trainers. They use consumerism to promote wellness and, by extension, happiness. According to McKinsey, the global wellness market is estimated to be over $1.5 trillion. Behind the promise of an ideal life, companies take advantage of the desire for happiness. They sell skincare and workout sets while insisting that the key to wellness is simple: to glamorize existence. ‘Wellness’ has nothing to do with health and everything to do with an inaccessible appearance of health. Even for those who break away from the cycle of sorrow, wellness that defines itself by aesthetics leaves us far from true happiness.

Achieving that happiness becomes near impossible when we overromanticize life, but one of the most threatening things about romanticization is that it works. I get more work done while I’m sitting at a cute cafe. I feel better about my life when I walk under a magnolia tree as the petals fall to my feet and imagine which angle the shot would look best from. Still, I find myself wondering if it’s better to be productive and maintain a superficial yet satisfying sense of purpose or to live truly. Is an honest life worth living if I don’t feel like the ‘main character?’

Maybe we find happiness when we find truth, when we see the world as it really is in its purest form and love life anyway. Redefining the common notion of beauty to reach beyond what we can see and finding this new version of beauty in hidden pockets of life may provide a sort of healing. By appreciating life as it comes, we can reject consumerism and reclaim happiness.

I’m writing this piece in my bed. The room is dark, I have a few more chins than usual, and there is nothing aesthetically “beautiful” about what I’m doing. Nonetheless, I find a certain joy and beauty in it, but it’s nothing I can describe with words or cut into a corecore video. It’s pure and real and honest.