Preparing for a spirit circle is easier than you might think.

Your first stop could be Spectrum-India, the “metaphysical supply store” straddling the corner of Thayer and Olive Street. Step under its deep blue awning, pass through the glass door, and enter a land of plenty: red and gold bangles, purple embroidered cushions, statuettes, tarot cards, jewelry, and something called “The Goddess Dress.” Though the dizzying swirl of colors and scents might tempt you to stay forever, focus now—swoop around a corner of self-help books, past a “Remember, Stealing is Bad Karma” sign, and onwards to your spiritual weapons of choice: a milky white candle and a box of frankincense. Feel how light they are in your hands, how heavy their purpose.

Not that you need them, really. “How to Form Spirit Circles” from the November 15th, 1872 issue of The Spiritualist, a publication for all things spiritual, makes no mention of them. In fact, a group of “four, five, or six individuals, about the same number of each sex” and an “uncovered wooden table” are the only requirements the article specifies. But if your spiritual organs aren’t feeling particularly developed, a bit of incense and candlelight can help you get in the right mood.

Outside of the store, your munitions tucked into your bookbag, catch your breath and craft an iMessage for your chosen accomplices. Something casual, yet direct.

“Would you be interested in sitting around a wooden table and trying to communicate with the dead?”

The sequence of events that led to me holding a seance on a school night began with a long overdue visit to the John Hay Library. An elegant white marble building, it hosts a number of special collections that interested students can request to view. During my time at Brown I hadn’t taken advantage of what it offered, and as a senior in my last semester, the clock was ticking.

While browsing through the list of archives the library houses, the Damon Occult Collection and the H. Adrian Smith Collection of Conjuring and Magicana caught my eye. Along with many of my third-grade peers, I had been an avid Goosebumps reader and dabbled in online spooky-story writing pages like Creepypasta; the collections reminded me of the thrill of reading amateur horror stories beneath the covers, way past my bedtime. A few requests for materials later, I found myself in the Gildor Family Special Collections Reading Room, staring out the window at a plaque dedicated to H.P Lovecraft. To my left: five boxes full of magic paraphernalia. To my right: enough old, yellowed manuscripts on demonology for me to give summoning Ctulhu the old college try.

I decided to save the occult for later and eased into the boxes from the Smith Collection. A deck of faded cards consisting only of the 10 of spades, four interlocked silver rings with a hidden gap, a wooden wand tipped with ivory—the collection included a broad selection of tricks and gadgets employed by magicians, including some belonging to H. Adrian Smith, a practicing magician and collector of magic items himself. One item that stood out in his collection was a prop head simply labeled “Harry Kellar prop head used in ‘Blue Room’ magic trick.” Life-sized and surprisingly lifelike, the prop was painted to reflect the forehead wrinkles, deep gray-blue eyes, and large gray eyebrows that the 19th century magician presumably sported.

Curious about the “Blue Room” illusion that I imagined took the world by storm in the late 19th century, I found a video of it being performed online and was initially disappointed—it showed a man vanishing and reappearing so seamlessly that I dismissed it as digital editing. But further research revealed that the trick, known more popularly as Pepper’s Ghost, really does look that convincing when done professionally. It involves two rooms, one visible to the audience and another one hidden. The hidden room, often blue in color, is where the person to be projected stands, and thanks to a trick involving a particularly angled plate of glass and a light source, the person is then projected onto the visible stage or room. It wasn’t entirely clear to me where the prop head fit into the trick, but I imagined it could be useful as a stand-in for any part where the magician had to pretend they were still in a certain spot.

I had briefly ventured into the world of magic before, learning card tricks well enough to try a few in front of friends, but not well enough to have them succeed, and I had forgotten just how powerful a trick can be. When done well enough, it can make you believe that even disappearing into thin air is possible.

If the Smith collection reminded me how powerful the suspension of disbelief could be, the Damon collection made me realize how far it could extend.

It started with the oldest and greenest book I’d ever seen.

Roughly the size of my hand, its lime green cover was partially torn. I could still make out the faded illustration on the front showing a general standing by a forest campfire with a bicorne hat atop his head. Above both man and hat hovered a title: “Bonaparte’s Oraculum.” The book, from 1830, was a transcription of the nearly 700 year old oraculum, or Book of Fate, that was consulted by Napoleon Bonaparte for important occasions and apparently held as one of his most sacred prizes.

I was once again struck by the idea that anyone, even someone as powerful as Napoleon, could be sucked into the thrilling world of magic if they let themselves believe in it. The collection also included guides on communicating with spirits, detecting elementals, and conjuring the astral projections of plants, among other activities you might get up to on the weekend. For me, the pieces served as a reminder of our morbid curiosity about forces we don’t understand and yet draw us together.

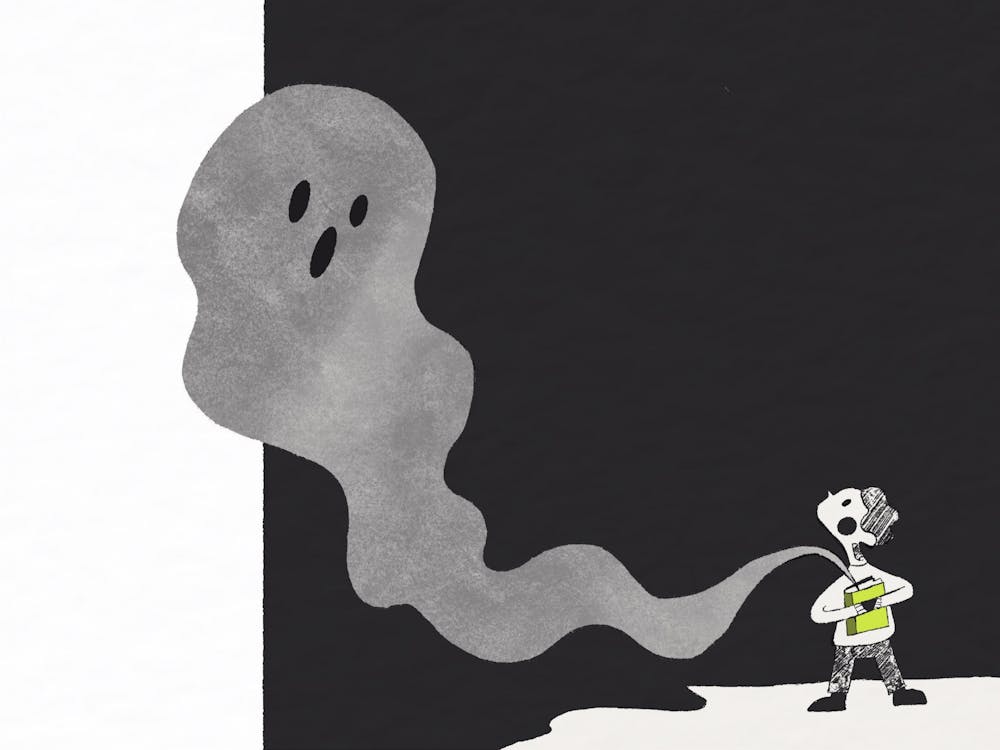

Even though I didn’t really believe in the content of the occult manuscripts any more than I did in Smith’s magic, I still found myself getting tangled up in the worlds they were selling to me, if only for a moment. A bit of research on how to hold a seance, which in my mind represented the ultimate suspension of disbelief, led me to the Spiritualist article that set the stage for my Wednesday night plans. I wanted to craft the same brief scent, the barely detectable taste, the whisper you fail to tell yourself wasn’t there — the split second where you think to yourself, “What if?”

Ivery mixed the drinks and UV ordered the dessert. Sam shared his own ghost stories while we made our way through chocolate puffs and sugared churros. Evangeline explained why Annie referred to her as her most haunted friend, and Maia poked fun at me while I used a screwdriver to burrow a hole for an incense stick into an old candle.

While the mood seemed more well suited for a party than a seance, we were actually following “How To Form Spirit Circles” to a T. One of the first rules that the article outlines is that “people who do not like each other should not sit in the same circle,” and unless some well-hidden grudges reared their heads tonight, it looked like we were in the clear.

I had been supplementing the older article with a Wikihow article on the same topic, in case any advancements had arisen in spirit communication since 1872. It was the more contemporary article that encouraged the candles and frankincense, and suggested that we find a particular spirit to focus our summoning efforts on. Thus, I’d researched and discovered a man by the name Fayette P. Brown to serve as our spirit of choice. He had lived in our house in the middle of the 19th century, fought in the Civil War, and died in 1890. Our method of communication with Fayette, if all things went well, would be through rapping on the table. We would ask to communicate with him, then ask him to rap once for Yes, twice for No, and thrice for Doubtful.

To get in the proper receptive mood, we held hands and agreed to meditate in silence for a little while, eyes closed. A few things entered my mind the second the world went black. First, how loud the sound of me swallowing my spit was. Second, the absurdity of the scene we were building, and an intrusive urge to laugh. But after a little while, it hit me—we were going to try to communicate with the dead. I dared to open my eyes and took in the scene around me.

I’d brought a notebook with the incantations written in it in case I forgot any during the seance, but I could barely make out the scribbles through the flickering of candlelight. Oddly enough, I felt a bit of pressure begin to set in. Would I get the words right? What tone do I use to convincingly talk to the dead? I had stepped over the precipice and let myself believe, and with that mindshift came a bit of weight. I looked around at my fellow occultists, and although it might’ve been the ghastly candlelight dancing atop their faces, I sensed that they had felt a similar change. The sound of rain and wind outside and the dark, quiet room consumed us. Deep in thought, hand in hand, the “What If?” moment had reached us all.

I called us back and began the seance, invoking the spirit of Fayette P. Brown and asking that only good spirits visit us. I asked if any spirits were with us, and we waited for the rapping. A floorboard creaked and we exchanged glances. We were creating this world together; how deep would we let ourselves sink into it? Annie heard a howl behind her, but UV swore he wasn’t pranking her. We waited long enough for rain to patter on the window—should we have counted it as one rap? Two? None?

The spaces between potential raps got wider, and soon the moment faded. I began the closing incantations.

Afterwards, while chatting about how we felt, a few of the others also mentioned really considering the possibility of making contact during the few minutes we were meditating. Even though we had entertained that feeling for only a moment, I was glad we had gone through with the seance.

Once everyone had left, I double checked the register where I’d gotten Fayette’s name from and realized I had misread it — our house had been owned not by Mr. Fayette P. Brown, but by Mrs. Fayette. Would the raps have been stronger if we had addressed her instead? Was the howl Annie heard one of indignation, of outrage at being mistaken for her husband? What if we had waited longer before ending the seance? Would the spiritual world have better service on a weekend?

The answers to all these seemed within our grasp. All it would take were a couple more candles, a healthy dose of belief, and another rainy, dark Wednesday night.