cw: mentions of sadism and violence

Bare feet against the bathmat. The mildew in the caulk. The crack in the baseboard, like a hyphen in the wood. And, of course, there were the ants, sliding down the wall like electrons on a wire, into the crack.

My sister and I decided not to tell our parents about the ants. We decided this without speaking, the way we decided everything at that time. We would deal with them ourselves.

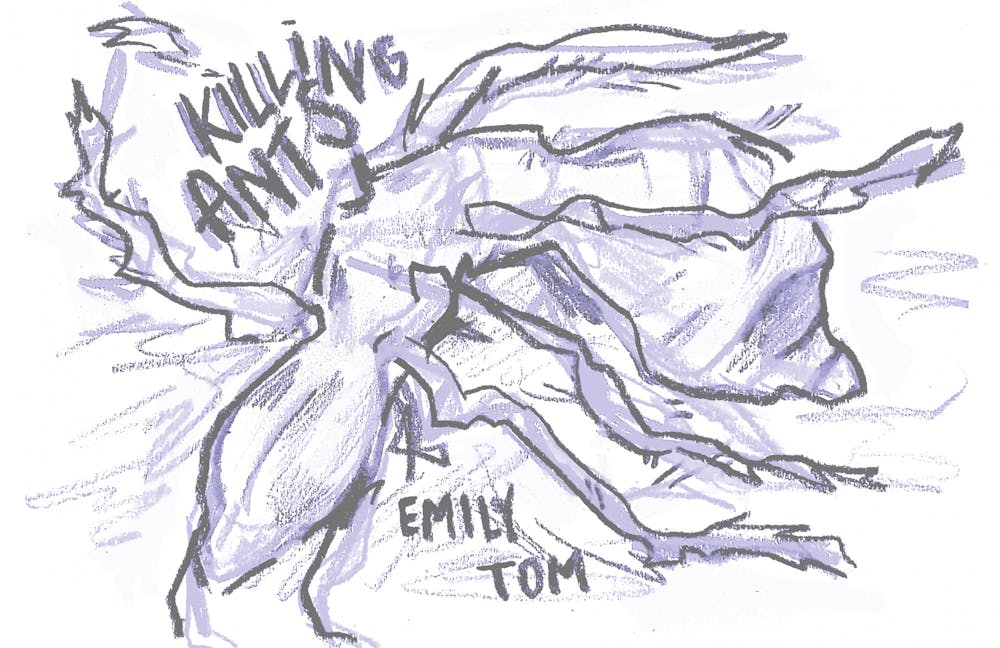

We crouched over the crack in the baseboard—the mouth of the nest—and covered it with Scotch tape. A few days later, when we saw an ant travel beneath the tape with ease, we took the plastic cup from the edge of the sink, and poured water into the crack. When that failed, we started killing the ants one by one: rolling them between our thumbs and forefingers, like eyelashes bearing wishes, or turning on the faucet and watching them spiral down the drain. We quickly learned that it is not difficult to watch something die.

It is tempting to say I killed ants because it made me feel powerful. When I told a friend I was writing about the way I used to kill ants, I prefaced it by saying, “I swear I’m not a psychopath.” He asked, “Are you ashamed of how much you liked it?” And I said yes.

But that was not the reason I enjoyed killing them. I think of how I was then, at seven years old: large front teeth, big eyes, crooked bangs, which my mother cut in the bathroom once a month. I was bad at sports and bad at speaking in class. I was afraid of bad grades and bullies. I had nightmares about Night Marchers and doppelgangers. But I loved killing these ants. A little girl who loved a little violence.

What I had enjoyed was imagining myself as the ant being killed. I found a lot of peace in picturing my own death. When I couldn’t sleep, I would think about drowning in shallow water, and it would tire me out. Girls die tragically, and their tragedy is beautiful, and I wanted to be one of them. I knew I would not enjoy dying as much as I enjoyed the fantasy of my own death, so I just watched other things die instead. And I envied them for it.

I remember brushing my teeth and seeing an ant scuttle across the countertop. I crushed it with my fingertip and stared at the corpse: a mangled black teardrop against the granite. Slowly, the ant untangled its legs, unfurled its body, and limped away. I did not know how it could have possibly survived, but because it did, I let it live.

Once, around the same time we started killing ants, my sister and I were walking through an outdoor mall. She closed her eyes and held out her hands. “I’m blind,” she declared. “Be my guide dog.”

I took her hands and led her into a pole. I thought it would be funny. She bit her tongue so hard that it bled. She started to cry. I stood there like a shadow as my father gathered napkins from the Subway next door and cleaned up the blood. I did not know why I did it. I felt awful. But afterward, when the bleeding stopped and my father threw the napkins away, my sister held out her hands and said, “Let’s play again.”

Like most younger siblings, she wanted to be just like me. When I started ballet lessons, so did she. When I ran for student council, so did she. When I joined the speech team, so did she.

And yet my sister still managed to be my opposite. My sister: who is unafraid of stages and spotlights. My sister: who is younger than me, but always insists on driving us everywhere. My sister: who has always been more than capable of handling life on her own—more capable of handling life than I am—still chooses again and again to follow me.

So as children, we killed ants to kill time together. We killed ants in the morning before school, standing side-by-side, brushing our teeth. We killed ants in the evenings, when we wrapped our sopping hair in identical twisting towels. Sometimes, when we killed an ant, another would find its body. The second ant would touch its antennae to its brother’s body, a strange kiss, and run in circles around the corpse. We would let the ant grieve, then kill that one too.

My sister and I shared a bedroom our entire childhoods. Our twin beds, parallel to each other, like two halves of an equal sign. We would lay there at night, staring at the glow-in-the-dark stars pasted on our ceiling, and joke about how many ants we must have killed. I thought we were in it together, that we shared a fascination with pain the same way we shared a room.

As we grew older, and as my anxiety grew worse, she was the one who witnessed my sleeplessness, my crying every night, my shakiness every morning. I remember, when she wanted to talk to me about it, telling her to shut the fuck up, get the fuck away from me. I remember never apologizing.

And I remember the way she used to wade through our backyard after a storm, puddles up to her ankles, and scoop drowning gnats out of the water with a dead leaf. When I think about my sister after the rain, I am convinced that she only killed ants because she was following my lead. I wonder how many horrible things my sister would have done if I had asked her to do them. I began writing this because I wanted to write about sadism, but instead I found myself writing about sisterhood. Maybe there is very little difference between the two. She wouldn’t have killed the ants if I hadn’t wanted her to, and I wouldn’t have wanted to if she hadn’t agreed to kill the ants. Our partnership fed off of itself, like a snake swallowing its own tail. We killed ants all summer.

That was until school started again in August. My sister entered her first year of kindergarten. I started the second grade, which meant I was allowed to borrow nonfiction books from the library. In an illustrated encyclopedia of insects, I learned that all worker ants were female, and suddenly, I wanted the ants to live. If the ants had all been boys, maybe I would have thought differently. But now, when I saw one ant run in circles around the crushed body of another, I saw a girl grieving her sister. I saw my own sister, with blood on her teeth, and myself standing next to her, with the knowledge that I was the one who made her bleed.

When I say I am ashamed of myself for killing the ants, what I mean by that is: I am ashamed of how easily and unquestioningly I hurt something. And what I mean by that is: I am ashamed of how easily I hurt my little sister just because I was hurting. And what I mean by that is: I’m sorry.

After I returned the encyclopedia to the library, I stopped killing ants. My sister, as always, followed.