After sunset is the blue hour. The sun is just below the horizon, and on a clear day, the remaining light scatters through the air, turning everything blue. At some point, you must have pushed out of a door, rolled down a window, or dragged a trash bag to the driveway and suddenly felt that blue air plunge into your lungs. You can taste the difference like you can smell a storm before it arrives.

At the beginning of 2021, I was home in Beijing, taking my first university classes online, living with my parents for the longest time since I was 14, and feeling confused about everything. I decided I couldn’t stay home forever, and that I would come to Brown for the summer semester, even if it meant uncertainty regarding Covid and my visa status. In the few days after that decision, I started taking more evening walks around my neighborhood. I told my parents that these walks alleviated the headache that arose from staring at travel documents, which was not a lie. Mostly, though, I was using those walks as a way to process the approaching goodbye.

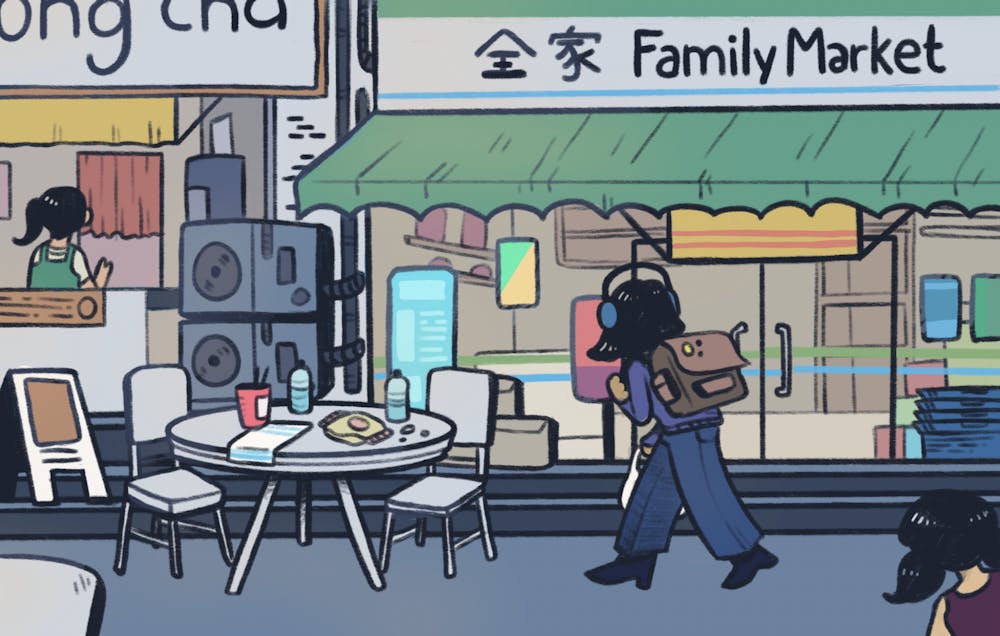

On those walks, I started listening to Sigur Rós again, an Icelandic band whose music sounds like long train tunnels, whale songs, the end of a movie, and the beginning of something new. Svefn-g-englar, one of my favorite songs, seemed like it was tailored for the blue hour. The chime, the long droning sounds, and the low murmuring were the perfect texture on which to layer the sounds of wind, traffic, kids chasing down the sidewalk as the lights went up, and the city turning in for the night. Submerged in the blue hour, the streets that I grew up on became strange but cinematic. The neighborhood convenience store, which, in my memory, was crammed to the point of becoming a fire hazard, was now growing empty. Its windows were covered with bolded sale signs promising a final move-out at the end of the month, a fate that foretold my own. Through the windows above the convenience store, the apartment lights flickered on and off as people returned from work, shuffled the contents of bags, walked in and out of rooms, and tucked children into beds. I pictured myself with my family framed by a similar window, and a premature sense of nostalgia tinged those images as I thought about saying goodbye. It was a nostalgia that I only knew how to process by looking at it from a distance, so I walked again and again in the blue hour, until my neighborhood felt like a reproduction of itself in a dream, where the details grow more vivid and bizarre the closer you are to waking up.

This was not a new feeling. For me, the blue hour has always been conducive to strangeness and unreality. Before I was in Beijing, I spent much of the beginning of the pandemic in Massachusetts with extended family. During the evenings, I walked the dog in suburban streets and glanced at lit-up windows that looked like scenes that Edward Hopper never got to paint. As a child, my favorite thing about America was the suburban houses. They seemed like the real-life version of a two-story wooden dollhouse that I received on a birthday, a familiar lens through which to see the culture that baffled me for most of my time in the United States. Unlike the dollhouse, which I knew inside out and could rearrange however I wanted, American culture remained frustratingly out of my grasp. But in the blue hour, houses turned into large dollhouses again, so when I wandered down the street and caught glimpses of half a person, the evening news, a small photo frame, or just the front porch light that stayed on throughout the night, I could feel like I was a part of them, and that I was someone who understood their significance. Once I went back inside one of those houses, I was again overwhelmed by confusion, but out in the open blue air, I could walk on as if I understood.

In many ways, the summer of 2020 brought me back to those days of relying upon distance and pretense to process culture shock. Not only had I returned to the same house, but I was also once again completely bewildered by my surroundings, thanks to the changes brought about by the pandemic. Day-to-day quarantine life passed by hazily, but out in the clear blue air, strolling through empty streets dimly overcast with spotted shadows of maple trees, for a fleeting moment, I could escape to an alternative universe where everything was normal, and the days were simply rocking towards a known destination like the trains that pass through after midnight.

A year later, a friend would send me an essay collection by Rebecca Solnit called A Field Guide to Getting Lost. In the essays, Solnit repeatedly goes back to the idea of “the blue of distance”—the mysterious blueness that tinges distant sceneries. She talks about 15th century European paintings that tried to create the illusion of depth by drawing small blue worlds in the distance. Looking at those paintings, you can almost imagine that if you took a walk in them, you would eventually arrive at a blue world with blue houses, blue fields, blue sheep. But Solnit’s point is that, in reality, the blue of distance can never be reached. It is a romantic idea whose appeal lies in its unattainability.

It seems that the blue hour brings the blue of distance—or at least the illusion of it—to us. Walking in the blue hour is the closest approximation of arriving at the small blue worlds in 15th century European paintings. If I can believe I have reached the unreachable destination, I can also believe I have comprehended my surroundings, resolved the emotions about a looming departure, and peacefully accepted the unpredictability brought by a world-wide pandemic. For 20 minutes, this blue illusion drags me out of the tangle of emotions and fills me with a feeling of perching on a side of a hill that overlooks the unending rooftops of my city. From this distance, it is hard to not think about how small and inconsequential everything seems, and when the day-to-day becomes stifling and sticky, seeing things in this distanced light is a much-needed respite.

But distance cannot always veil the turbulence in my surroundings or smooth over the edges of my emotions. After a few months of preparation and clinging to the blue hour for respite, I set off to the United States for college. During my stop in Singapore, I found myself sitting with a new friend on a hotel rooftop in the blue hour. It was not a particularly tall building, so we were surrounded by city lights and humid summer air that smelled very different from home. Across the street, we watched a man shuffle slowly between his car and an apartment entrance, his shoulder weighted down by plastic bags on each trip. I stumbled through a description of my feelings towards the blue hour, then asked if evenings like these also made my friend feel detached but peaceful, to which she answered: “Not really, I’m mainly wondering if that guy had a nice day.” I took a harder look at the man, then at my friend’s face illuminated by the city lights.

In the end, I arrived in Providence, and by the winter of 2021, I had already completed two semesters at Brown. I spent my winter break in my dorm room, sitting quietly with my books, taking long walks in the snow, attempting to replicate my family’s home cooking, and taking care of plants that my friends left me with. Alongside the little garden of potted plants that occupied my windowsill was a UV lamp with a bright violet-pink light bulb that they had left me, so when I walked back to the dorm at the end of each blue hour, my window stood out unmistakably in the view from the street. As I grew more accustomed to wandering around a quiet campus, that violet-pink color of my windowsill also seeped into a corner of my blue hours. It became a kind of connection that eased my distant blue world into a real, vibrant one that contained my friends, their potted plants, and the smell of my improving cooking. When I returned to the dorm with my lungs soaked in blue and my fingers frozen, my violet-pink window gradually closed the blue of distance in my mind, and I was back to being one who gazes into the distant blue haze in a painting, rather than someone who walks in the small, imaginary blue world. At the top of the steps leading to the front door, I am again enveloped by my immediate surroundings, my confusing, uncertain surroundings. Then, when I go up to my room, I am greeted by the same light on my windowsill, signaling as brightly as ever into a dimming sky.