He hasn’t moved from the kitchen table. Yesterday’s hard-boiled eggs and toast sit untouched on his paper plate, no doubt cold. Everything but his left hand remains still. He’s been rewriting the same word, over and over. In harsh, repeated lines, I can read clay. I’m surprised the pen hasn’t given out yet. But the paper is ripped. And instead of moving to a new section, he continues writing into the wood of the table.

The rest of him isn’t frozen; if anything, he’s burning. Yesterday, I tried shaking him awake, reaching for his forearms the moment he went silent but immediately recoiled. A thick, red line licked its way up the inside of my wrist. It left a mark, but I know now not to touch him.

My father never got to read my writing. Which is kind of funny, because I write about him a lot—not all good things, so honestly, maybe it’s for the best that he never got to read it.

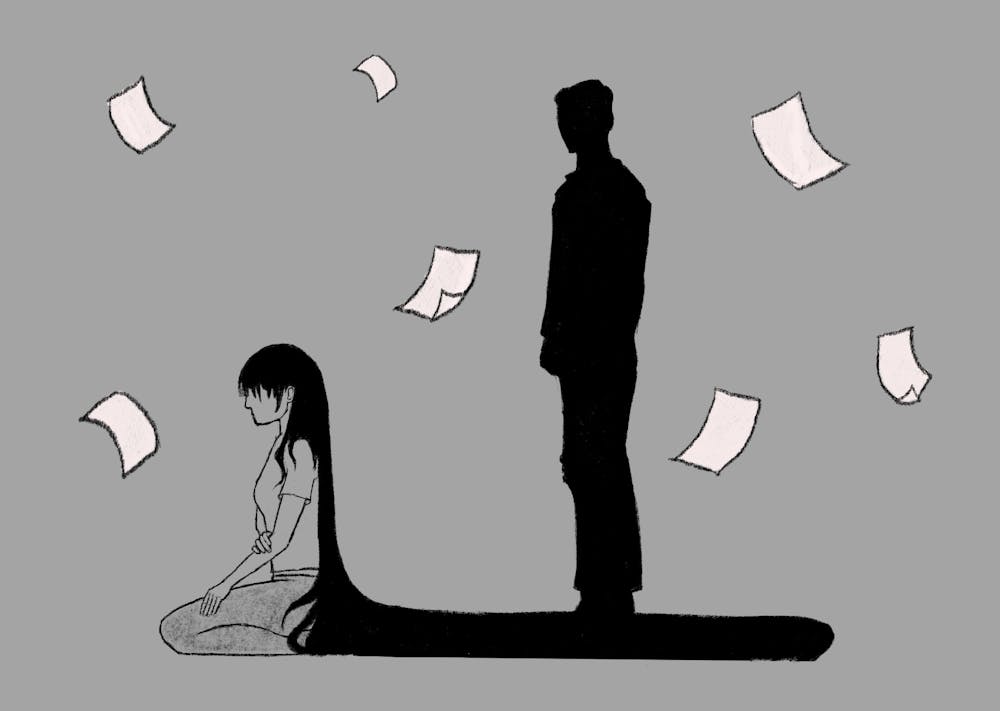

My dad died around this time last year, in perhaps one of the worst ways possible. I’m not going to get into it, but you can trust me—you don’t want to die that way. In a lot of my short stories, the father figure disappears, or dies, or was never there to begin with. Because of this, a strange part of me felt his death—the cause, the time, the place—was inevitable, that deep down I expected it to happen. Honestly, the whole thing still haunts me. So many things about him still haunt me. And maybe that’s why I keep writing about him.

Ben looks past me, peeking into the room. I follow his gaze and gesture for him to follow me. We step inside together. The floor creaks with our combined weight, mixing in the air. Dad’s still there.

Dad’s still still.

Still.

For a moment, we didn't say anything. We just watch. The sound of our dad’s scribbling growing louder and louder.

Ben breaks the glass first: “Should we call someone?”

I shrug my shoulders. “Give it another day. He’s just grieving.”

Ben hums in response. We don’t say it, but we can both feel the heat. It pecks at our cheeks, brushing our arms. If we got any closer, no doubt we’d burn.

It’s interesting to think about how, while alive and dead, my father’s still here. Buried deep in my bone marrow, in the pieces of skin I tear from my fingernails, in the soreness of my jaw from clenching too hard. He’s there in the nights I can’t sleep and toss and turn and lay staring at the white ceiling. He’s there in the shadows I spot in my peripheral vision, the figure always watching me from the corner.

But he’s also there in the green thermos he gifted me junior year of high school; in the black journal he gave to my aunt to give to me—the last, but also first birthday gift he gave me that wasn't a knife, or a switchblade, or some kind of weapon. Honestly, it’s kind of ridiculous how many knives I have that he gave me, how many my younger siblings also have.

My father’s also there while I’m working at Andrews as a Brown Dining student worker. He worked a lot in kitchens. I think we’d be able to have a nice conversation about our kitchen experiences, something we could shit-talk and maybe laugh about. Very rarely could we laugh about anything together. My dad was a sarcastic man. He’d always say, “Where’d you get that sarcasm from?” And, if he were sober and in a good mood, I’d shrug and say, “Well, I learned from the best.”

He’s there when I feel the sudden urge to text him, short and quick. A small update: school’s going alright (lie), I’ve been busy with assignments (a half-lie), I’ll try to call you later (a complete lie), and I hope you get some sleep (the truth). I used to update him because, one, he got angry if I didn't and two, because I felt bad when I didn't contact him. But honestly, I ended up feeling bad regardless.

There’s something distant in his eyes, a little glazed over, a little lost in gray. Give it another minute, maybe he’ll tell me to leave, maybe he’ll tell me to start dinner. Or maybe he’ll just sit there. Again. All through the night, hands clasped beneath his chin, breath shallow. Ben sits with him when he’s not at work. Sometimes I walk by, allowing myself to listen. Dad doesn’t seem to say anything, but that doesn’t stop Ben from talking.

I don’t like going in the room. The burn on my right forearm starts itching whenever I get too close. Ben doesn’t know I touched him; he was at the diner when it happened. I hid the mark, its blisters concealed under long sleeves. But the heat itself, like a roaring fireplace, reminds him to keep his distance.

My father used to joke about me writing about our family. “You should write about us,” he’d only say this when he was drunk, “about me.”

I think my father took some strange pleasure in knowing we weren’t a ‘normal family.’ That alcoholism, domestic abuse, mental illness, and low-income struggles existed in our two bedroom house on the Navajo reservation. He’d make jokes about how all the great writers, all the “great artists,” were alcoholics or came from “troubled” and “messed up” backgrounds; that I had “great” material to create from—to spin off of and write about.

And in some ways, he was right. I write about him and the things that happened to us. I write a lot about growing up. And I write a lot about how growing up the way I did affects me now. I don’t know if he’d be proud or if he’d get angry. And I’ll never find out. There’s a nice finality to not knowing.

When we get back, our father is gone. We search every floor of the house, checking each room twice. I dig through closets, crawl under beds, and worm my way between shelves in the basement. Ben drives into town, searching along the highway. He drives two towns over, sometimes three. But the answer is always the same. No one knows, no one’s seen anything. I wait at the house, in case he comes back. I’d like to think he’d come back, if not for us, then at least for the clay figurines he left behind. The ones he made with his mother. He wouldn’t just abandon them.

During 2020 Covid summer, I’d call him every now and then—or rather, he’d call me. If it was early enough that I could trust he was sober, or if I was feeling particularly brave, I’d answer. I remember he’d ask me what I was writing about. I never had the courage to tell him what I was actually writing about, so I’d give him a general response: “Just some short stories.” Take a light breath, keep my voice even so I don’t sound suspicious, “I’m not sure how to describe them.”

He’d grunt and say okay, followed by some variation of, “but you gotta show them to me someday.”

I’d agree just to agree. Because he’d have it no other way, and, despite being over 2000 miles from home, I was still afraid he’d hurt me.

All of this sort of comes down to that single, irrational, and stupid-ass crushing thought: I’m still afraid.

And what’s my solution? Motherfucking writing about it.

I used to write about things under a pseudonym. Whatever I was feeling, whatever was happening at home, whatever I wanted to say but wrote instead. I never used first person point-of-view, and I never used my actual name. This was my first dabble into fiction writing, which was also strangely my first dabble into self-narrative. It just made sense at the time. I don’t know whether I wrote like that to protect myself from outside readers—my dad, my mom, my school teachers; or to distance myself from my traumatic experiences. Perhaps it was both.

I place the clay figurines along the windowsill. Their forms cast small shadows, coated in sunlight. They’re our new lookouts, calling our dad home. We moved the table our father sat at for three days into the basement. Sometimes I go down there and trace his handwriting, following the engraving with my forefinger. The jagged lines suggest pain and grief. The depth of the engraving suggests frustration, maybe even anger.

We don’t know how he felt leading up to his disappearance, but something tells me he found at least a fourth-of-a-cup of peace. Maybe it’s the fact that my forearm has healed, blisters gone, only the smooth finesse of a scar left behind.

I don’t write like that anymore. But sometimes I wonder if I’ll ever be able to write about anything else, not distinctly father- or trauma-related. I’d be lying if I said my short stories, that are works of fiction, don’t also carry pieces of my past. And I’d also be lying if I said I knew how to write—how to exist in my day-to-day—without those pieces.

Me writing about these things, and sharing them, is the healing process. There’s something comforting in knowing another person, whether I know them or not, will read these words and understand me a bit better. Or perhaps they’ll read these words and not care, because honestly, why should I expect them to? These are just things, emotions, thoughts, glimpses, memories, feelings, images, tastes, smells, conversations, experiences that I need to write about. And they won’t leave me alone until they’re out. I can always breathe better afterwards.

To this day, only two of my family members have read my writing—my two older cousins. But they were pretty mellow, a previous post- piece about my sky blue Nintendo DSi and the fiction snippets in this piece. Honestly, I don’t look forward to sharing my writing. I’m not sure how it will go, if it’ll be invalidated or brushed off. But I’ll always be haunted by the things I feel compelled to write about, and at least I’m growing more comfortable with sharing those thoughts.