CW: disordered eating, self-harm, blood

We were out of band-aids.

Shit.

The carpet. Blood. I need hydrogen peroxide. Where did I put it?

I’m vertical now, hobbling across the hallway, on the ball of my left foot and the heel of my right. The carpet’s going to be stained. One spot, two, three, four, I count. Where’s the hydrogen peroxide?

A flash through the window of fall—not real fall, but San Diego fall. Muted olive leaves. Paper pumpkins pasted on front doors. My skin feels cold. I fold a length of toilet paper, twisting it until it’s taut like a rope in my fingertips. I perch my foot on the edge of my bathroom counter, a surgical table now, a sterile field, the rope wrapped around my big toe, tied tight.

Now I can walk faster. Hydrogen peroxide. Laundry room. I enlist my tiptoes to reach it, my rope turning from white to red. I look down. Red enlarged. Rope weakened. Hydrogen peroxide. Collateral damage always comes first.

I never intended for it to happen, it just always seemed to. I don’t remember looking away from the smudged autumn skies and digging my fingers into the cuticles of my toes, peeling the corner of my toenail down further and further until I saw blood, foraging the terrain of my feet in search of unfastened skin, nail, scab, anything to amputate, to peel. All I remember is the awakening, the way pain pulled me from the chasm every time. The way it made me feel alive.

My therapist once referred to my skin picking as a “powerful expression,” and I like that, because it’s true. Inflicting pain upon myself, I do feel powerful. I have control over an entire narrative, a beginning and ending, an epic story of achievement. In the cafeteria of my high school freshman year, I couldn’t control the cold shoulders of 15-year-old girls, the ones that formed tight circles, closed me out, caused me pain. Fingers piercing my cuticles, I controlled the pain I felt.

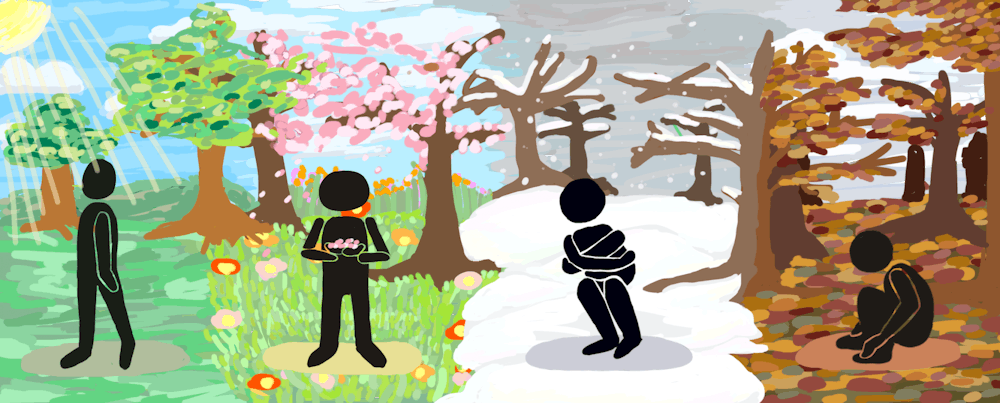

I’ve come to understand my behavior as seasons. The fall—the urge to shed, to transform—comes multiple times a year for me. San Diego was never one for metamorphosis, clinging to its summertime intensities even upon October’s arrival. Some leaves fell, but nothing changed. I didn’t understand that. When fall falls upon me, I want nothing more than to pluck the leaves off the tree branches of myself—scrape away an aged exterior in search of a cooler, more extroverted, more confident, more beautiful version of me.

I can never get the words out, that I want pieces of myself to fall down like leaves. So I spend my fall seasons hoarding gauze in my desk drawer in preparation for the inevitable—the forceful arrival of self-hatred, or insecurity, one that seems too enormous and heavy to translate into words—so skin picking becomes my expression. The aftermath is likewise a routine—cleaning the carpet stains with hydrogen peroxide, then sanitizing my cuticles before applying Neosporin, next stretching water-proof bandages around my nail-less pinky toes, and lastly sliding my feet into fuzzy socks. Done. How peculiar it is to be both an abuser and a caretaker of a body.

My winters come suddenly. Without warning, I find myself in these distinctive seasons of mourning, triggered not by a specific loss, but rather by the realization of all that I have lost. In winter, I again see myself in the trees, now with leaves fully fallen and left to stand naked in front of the suburban homes, grieving the colors they once bore—that disappeared without a goodbye.

It is during my winters that anxiety screeches to a halt. I’m no longer worrying about my appearance, others’ opinions, others’ words; rather, I mourn the time wasted ruminating over such superficialities. I find myself bowing down to the terror of time, realizing how much I have wasted the fruits it has provided me—the opportunities to cherish my family, my youth, my agency, my abilities, to see and do and think and say. The trees once wore so many leaves; I once held so many beautiful hours. We took our abundances for granted.

Once again, I find myself harboring emotions that feel too enormous for my body. My grasp craves every hour; I want to control every second, but I can’t. All I want is the ability to manipulate, to in some way control the ruthlessness of time. Those nights, when all I want is to seize the clock’s hands, I seize the thing that I can: food.

I never remember the decision to venture into the dark kitchen. I never remember my hands blindly foraging through cabinets for something, anything, everything. I never remember the taste or the texture, only the magnitude, the challenge to consume more, and more, and more. Life is so fragile—it may be my last chance.

What I do remember are the journeys back to my bedroom, wiping chocolate from my lips, stomach turned to rock, tears streaming down my oily cheeks. I told my therapist I wasn’t picking my feet as frequently—but, you see, self-sabotage never truly leaves you. It just changes form.

Spring offers her hand and I take it gratefully, allowing her to pull me from my seat in the darkness. During my springs, I am finally able to see. The naked trees outside my window begin growing tiny burgundy leaves and cherry blossoms—my favorite of their accessories. The sun slowly garners its past spirit, and I do too.

We think of spring as beautiful, watching the earth as it slowly reawakens from its hibernation and retains its summertime vibrancy. We don’t consider how painful this transition could be; we expect beauty to simply bloom at the snap of a finger.

I think others perceive my springs as painless, too, because they only see the exterior. The season, for me, is characterized by a desire to adorn myself with new accessories like the trees do—a flatter stomach, stronger legs, smoother skin, painted nails, “natural” blonde highlights. In anticipation of summer, trees are expected to become beautiful during their springs, and I set out to do the same during mine.

Now is when I will actually do it. Women’s Health endorses intermittent fasting, Eight hours of eating, sixteen of fasting; I am a woman of health, aren’t I? I am now. I am today. I had dinner last night at 6:30 p.m., so I can start my lunch during the last 10 minutes of APUSH. Done.“Running every day promotes muscle toning and strengthening!” Noted. “Fruit is obviously good.” “Fruit is entirely sugar.” Obviously. “Eat mainly protein.” “But eat only vegetables.” Done.

My June comes, and I do bear some cherry blossoms—I exercise daily, measure my portion sizes, finally inching closer to what I perceive to be beauty. That is what people see, the exterior; they don’t see the days of labor, the newfound addiction to calories, macronutrients, and green vegetables, or the swelling detachment from my family, my friends, and myself. Nobody considers how difficult it is for a tree to prepare for summer—our transitions are never as seamless as you perceive them to be.

My summers enter nonchalantly, and everything seems too slow. This season is a cruel respite, one that is needed but horrifying, one during which I have a moment to realize what a skeleton I am—scarred feet, a short-tempered digestive system, a brain encrypted with proper serving sizes. There is no part of myself left to sabotage. It’s the heat of my summers that shines a light on my own self-cruelty. I was and am a ruthless associate of my own destruction. And why?

It’s estimated that 17 percent of adolescents worldwide engage in some form of nonsuicidal self-injury. 7.8 percent are diagnosed with eating disorders. In 2016, it was found that 0.2-12.3 percent of youth internationally meet the criteria for problem gambling. 90 percent of adolescent alcohol consumption is in the form of binge drinking. Evolutionarily, it’s perplexing why a human being, inherently compelled to survive, would engage in behavior that could jeopardize their own well-being. But we do. I do.

For me, the skin picking, the binge eating, the restrictive eating, complemented with some occasional hair pulling and nail biting—it is all the same, the same urge to self-sabotage that just changes in color, form, and intensity alongside the seasons. Under everything lies a discomfort with my identity, a belief that I am broken, a fear of others’ alienation, and an uneasiness with growing up. Over the course of the past year, my family, my best friend, and my therapist have held my hands as I stumbled across these uncomfortable cobblestones for the first time, finally confronting what was harbored within me for so long. I still work every day to recognize my worth, to see myself as whole, as not just a shadow in others’ lives but a strong and steadfast daughter, sister, and friend. And I have improved. Greatly.

But even as I come to better understand the origins of my behaviors, they don’t stop. That’s what is so deadly about self-sabotage. Even when one’s brain has reckoned with the emotional trauma at the root of a behavior, the physical body is still addicted to the act itself—and will continually call on it in times of distress. Upon injury, the body immediately releases endorphins to act as natural painkillers. Research has proven that those who engage in non-suicidal self-injury have naturally lower levels of endogenous opioids (endorphins), and will thus continue reverting back to the habit to compensate. The same goes for other forms of self-sabotage. Binge eating, gambling, and alcohol consumption are all associated with the release of dopamine in the brain.

Thus, my addiction hasn’t left me. But it is the conscious ways in which I choose to reckon and interact with these instincts that have helped me find freedom from them. Chewing gum, cognitive behavioral therapy exercises, yoga, putty, velcro, fidget cubes, and paper clips are now listed in a note in my phone as intervention techniques, and I am proud to say these have helped me resist engaging in self-sabotaging behavior many times. My therapist is always proud. And yet, it is still fascinating to me how strongly my brain and body yearn to pick my skin, binge eat, or restrict. The temptation may always be a presence in my life, and I have to accept that.

Coming to Brown as a first-year, I wanted to be perfect. I still do. But after nearly three weeks here, of speaking with people, hearing their stories, and watching them unapologetically express raw, authentic emotions, I feel a little bit less afraid. I am feeling that maybe I don’t have to be perfect, that maybe everyone carries something like I do—that maybe just manifests, falls away, and reawakens in different hues than mine.

My mom asked how my feet were over FaceTime the other day. I lifted all ten toenails to the computer screen, still painted a light orange for the fall.