April is the cruellest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain.

- T. S. Eliot, The Waste Land, 1922

There’s a photo of our house from 1983, back when the exterior was painted a yellowed off-white—ivory, perhaps, in the right sun. The clapboard siding was the same then as it is now, the thin overlapping strips of wood that form our house’s ridged torso, a technique European colonizers called “dressy,” like a wooden skirt for a building, effective in protecting homes against New England winter winds while still letting warm air leak through in summer. Perhaps that was how our house braced itself for the “Megalopolitan Blizzard” of 1983, when 11.2 inches of snow fell in just one February day, and then was able to open up and breathe again on the 11th of September, when temperatures rose to their hottest levels of that year.

Ours is the 1898 J. Nickerson House of Providence’s East Side, a Victorian-style estate featuring large Greco-Roman-inspired columns supporting the second-floor balcony and porch overlay. Dentil work runs along the roofline, a type of ornamentation that uses a series of small blocks in a row. Below, we have bay windows on the first and second floors that jut out in assured trapezoidal ways, creating an asymmetrical body that bulges in some places and not others. Today, it’s dressed in blue—a periwinkle flushed with grey—except where the clapboards’ paint chips, and lucky parts of the old ivory emerge to feel Rhode Island rain again.

In the photo, there are still two front doors. Now, inside the left-most one is the red-carpet-lined staircase to the second and third floors, the very peeling wallpaper a toile pattern—a narrative design made up of repeated scenes centering around an event or theme. Ours must be pastoral: In one recurring motif, you can see a woman lifting a lamb, showing it to a winged deity. Everything is a dusty blue, and if you look close enough, you can see two different shades of it—a lighter one like pale cerulean, and tracings of something darker layered on top, the two creating shadow, life. Puffy human cheeks and fleecy sheep bellies, all the way up to the third floor.

I texted the 1983 picture to the group chat with all of my housemates. A, who lives on the first floor, texted back:

The stairs have not been replaced which makes sense bc every time I step on one I think abt how I could step through and die.

Yeah, I think that’s it: Our house is breaking. The landlord has banned us from the second-floor balcony, locking the door and holding on to the key. I wonder what finally convinced him it was no longer safe to step on—if a person fell through, their body crumpled up on the front porch like one of my Amazon packages. I imagine wood rupturing under me, plunging fast with severed bits, each time I stand on the other balcony, the one overlooking the backyard. And on the inside of the house, each of the red steps groans underfoot, angry like something ought to be, I reckon, when it’s been stepped on for 127 years. At the top of these stairs one afternoon, I opened the third-floor door and felt the handle come loose, the brass knob suddenly in my palm, surrendering itself.

—

After World War I, younger generations began to view the Victorian Era as overly extravagant and materialistic—so much so that, by the 1930s, the word “Victorian” became a disparaging term. Victorian-style houses, with their heavy facades and excessive furnishings, came to represent the corruption of a bygone age: Architect Talbot Hamlin went so far as labelling them “wooden monstrosities.” As these homes fell out of favor, gradually abandoned, artists employed them as metaphors for fear and terror. Films like Psycho and books like The Haunting of Hill House solidified Victorian houses as menacing spaces, where ostentatious histories festered—thick strips of black mold between the floorboards of my bedroom.

Perhaps Hamlin would laugh at me, sitting in the Rhode Island Hospital emergency room one Sunday in February. M was picking something up in her second-story bedroom when a piece of the hardwood floor became lodged in her left ring fingernail. She tried to pull the splinter out, only for the top part of it to break off, leaving her with a tiny piece of dark wood stuck in the skin underneath the nail. I watched her put her head into the right palm and breathe, visibly in pain, reminding me of the November night when Z’s window shattered, cutting the top of her hand open—the void in her window, letting all the cold in. Monsters who bite back.

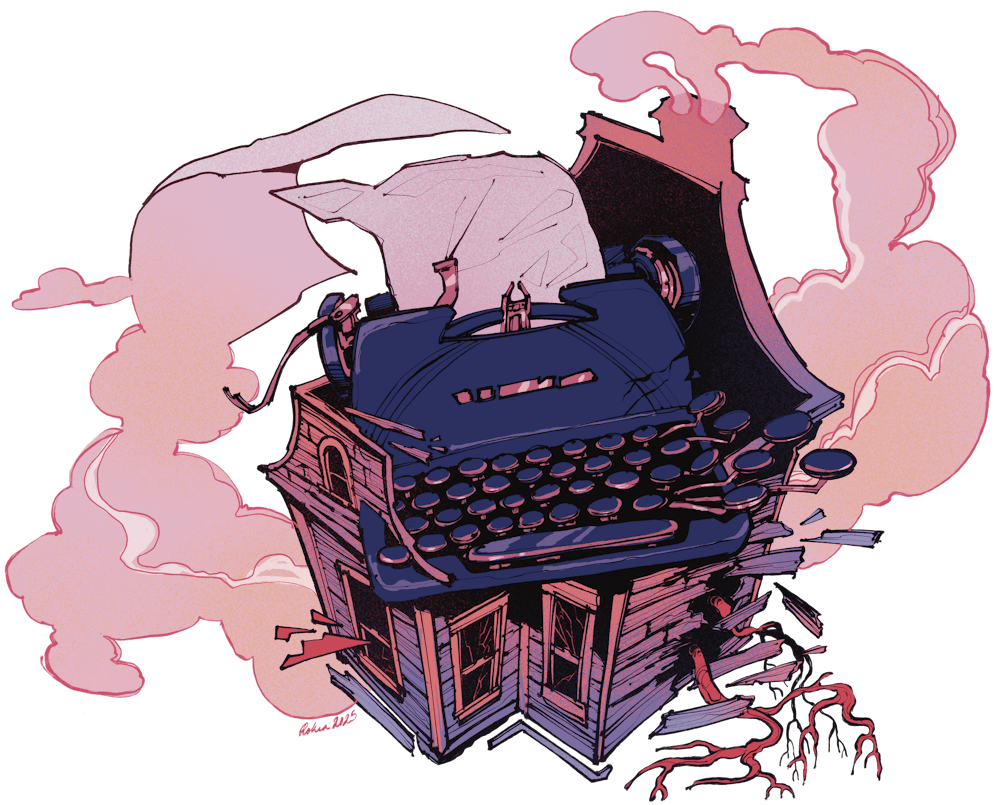

Someone asked me what J. Nickerson would think of all this, his ghost in the chipping periwinkle paint and the stairs that haven’t been replaced, the broken glass and the splinters pushed in skin, the Smith Corona mechanical typewriter that’s still on the third floor (someone wrote I LOVE CLUB SWIM with it.) I tried to learn more about him, visiting Providence City Hall’s Archives and hoping for a grand history to write about. A nice man named Antonio found the original permit for me, which declared Nickerson’s intention to build the house in 1896, but couldn’t find any other related materials. The 1983 photo was the only useful thing I found available online, except, I guess, for Nickerson’s ‘Return of a Death’ form on FindAGrave.com. A retired police officer, he died on June 17, 1923, in our house, signed away by his daughter, Mrs. William Waters.

Around the time I visited the Archives, I had to start thinking about a topic for the capstone research project for my economics concentration. Over Zoom in my third-floor bedroom, which is painted a subtle green, I said something to my economics professor about wanting to make research meaningful in a time like this. Whatever that means.

“I think all we can do is—” she sighed. “I think all we can do is learn facts about the world.”

I became excited to conduct economic research on maternal health, to learn facts about the world, if you will. But I had difficulty accessing the dataset my professor recommended, speaking on the phone with various CDC customer service agents to get around what I assumed to be a website bug. I found out later, sitting on the couch in the third-floor common room around midnight, that the presidential administration had locked researchers out of this survey data, and I suddenly felt terrible for bothering staffers who were likely very concerned for their jobs. Like in the Archives, I sought histories I thought to be alive and waiting for me. Histories that do not exist.

—

On many Sunday evenings, I talk to my grandfather. After discussing his puppy and writing, he usually mentions something about the news. He apologizes on behalf of his “generation;” I laugh and tell him it’s not his fault. On the 9th of March, several hours after my grandfather’s Sunday call, I sat cross-legged in thin pajama pants on the hardwood by the dining table and watched my phone change from 1:59 AM to 3:00 AM. I had never been awake to watch an hour be cut out, a wedge from a wall clock, to spring forward. We put our phones back down and continued our round of Mario Kart.

With climate change, spring is coming earlier. According to Temple University’s Jocelyn Behm, in a natural, pre-climate change ecosystem, “everything had evolved so that the timing all matche[d] up.” The birds migrated back around the same time the insects, which the birds feed on, emerged from their winter dormant states. “There is all this synchronous matching, and that’s what is starting to break down because all the species are responding in their own unique ways.”

From my desk on the third floor, I look into the branches of the American elm out front that press up against the window with the wind, sometimes catching a squirrel hopping onto my windowsill and then back into the tree cavities. Below, the roots bust through the cement like unruly wooden tentacles, and if you aren't careful, you'll trip on the rolling hills of our sidewalk. Perhaps, for the squirrels, it also feels like their home is angry at them for living in it. Perhaps that's why they've begun relocating to our outdoor trash cans.

I found out recently that the recurring motif on our toile wallpaper, of the woman holding up the lamb, actually depicts an offering—an animal sacrifice.

—

Our house has nothing to do with the state of the greater planet, government, economy. What feels the same, though, is the guilty joy we find in things that are falling apart. The water balloons thrown from our back balcony, breaking on our shoes in the backyard, laughing, wet and drunkenly. The second floor’s blue couch, how it traveled to us in K’s partially-open trunk, others sitting back there to hold it in. The evening after the Valentine’s Day party, when we sucked helium out of the red, heart-shaped balloons, or perhaps the quieter nights in our too-small kitchen, S cutting avocado with her favorite scalloped knife, the one with the pink handle. The way I am enjoying my classes more than I ever have before. My walks to campus among the daffodils that look like bright yellow flames.

The other day, a friend and I did a virtual workout class in the third-floor common room. At first, I thought it was a cardio class, the jumping jacks and high knees. But it wasn’t that. The woman encouraged us to let out noise, to sigh, to roar, which made the burpees a lot easier, and made everything feel like some kind of release. Holding a crunch position, she said, “Keep feeling for your center—which is all just love. If you are feeling tension or anger, you are not there yet.” It made me think of the inner core of the Earth, under all those layers of molten metal, which affects the length of our days.

My friend on a yoga mat and me on a bath towel, we danced, jumped, laughed atop my creaking living room floors, because maybe that is all we can do. My face pressed into the ground in Balasana child’s pose, I began to cry quietly for the hardwood that holds us.