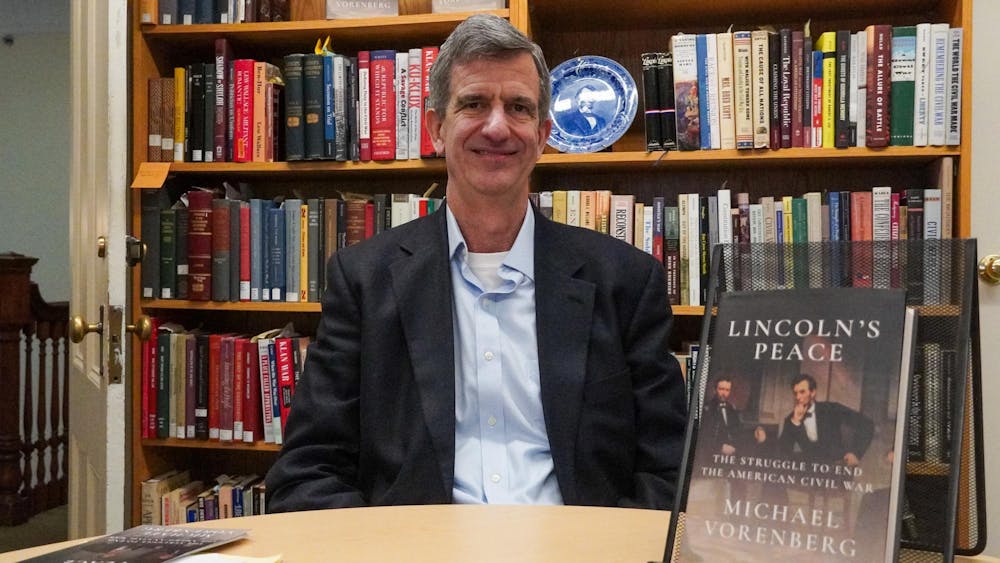

Last month, Associate Professor of History Michael Vorenberg published his new book, “Lincoln’s Peace: The Struggle to End the American Civil War.”

The book challenges the traditional narrative that the Civil War ended neatly in April 1865 with the surrender of General Robert Lee to General Ulysses Grant at the Appomattox Court House, Vorenberg said in an interview with The Herald. Throughout the book, Vorenberg examines the war’s many potential end dates while arguing that the endpoint one chooses for the Civil War defines how the war is remembered.

“The American Civil War has an official end date, and that end date is August 1866,” Vorenberg said. Notably, the official end date comes “16 months after the end date that we typically assume, which is the surrender of Lee to Grant at the Appomattox Court House,” he added.

Though the book was 10 years in the making, the idea for “Lincoln’s Peace” was born 20 years ago when the United States was grappling with ending their 21st-century invasions in Afghanistan and Iraq, Vorenberg said. He was struck by the parallels between the U.S. Civil War and the 21st-century wars: They both became conflicts “that could not be ended in any sort of clear and discrete way.”

Initially, Vorenberg did not think there was much more to learn about the Civil War or former President Abraham Lincoln.

“There are more books written about Abraham Lincoln, I believe, than anyone else, except Jesus,” Vorenberg said. “I don’t think any episode of American history gets more attention than the American Civil War.”

But after sifting through official records, letters and diaries from “as broad a swath of people” as was feasible, Vorenberg was able to uncover some new details about the time period, he said.

Vorenberg didn’t realize how “entangled” the Civil War was with conflicts in the American Southwest.

During his research, he also uncovered specific examples of conflicts that persisted after the war technically stopped, such as the story of a Confederate ship in the North Pacific attacking the New England whaling fleet in the summer of 1865, months after the war supposedly ended in Appomattox.

“Professor Vorenberg’s book is a testament to archival research,” said Seth Rockman, associate professor of history.

“The attempt to understand what the past is all about is an ongoing conversation,” Christopher Grasso, professor of history, said. “Some people call it revisionist history as if that’s a bad thing, but just like you wouldn’t hold it against your surgeon if your surgeon learned a new thing about heart surgery and applied that to his practice, historians do the same thing: Ask new questions.”

Vorenberg’s new book expands on his past scholarship on the Civil War and Reconstruction periods, which consist of several articles and books. His first book, “Final Freedom: The Civil War, the Abolition of Slavery and the Thirteenth Amendment,” about the creation and meaning of the 13th Amendment was the basis for the screenplay of Steven Spielberg’s film, “Lincoln,” released in 2012.

“Slavery doesn’t end on a date,” Vorenberg said. “And in the same way with the Civil War, what we have is the creation of essentially mythological endpoints.”

In writing a book that argues that the Civil War had many end dates, Vorenberg had to “be careful not to make (the) mistake of choosing an endpoint” that defines the war for himself.

“I think the biggest challenge was … knowing that I was going to frustrate readers who are looking for a single answer to the question,” Vorenberg said. “It doesn’t exist.”

Vorenberg hopes that readers will question “deeply held facts” and learn that even something as “dry and mundane” as a date “actually carries meaning.”

“We are currently watching our government seek to limit the scale of American history, to exclude certain stories from the national narrative,” Rockman said. “It’s more important than ever that our scholars produce stories that attest to the complexity and contingency of an American past that is very much open for interpretation and reinterpretation.”

Vorenberg has already begun on his next work: a book about a military prison “that existed during the American Civil War and Reconstruction” and “incarcerated more than 2,000 people over a period of eight years, and has been called the Guantanamo Bay of the 19th century.”