While many high school students are counting down the days until summer, Julianna Espinal — a junior at Classical High School and a youth organizer with activist group OurSchoolsPVD — has spent the last year fighting for an ethnic studies curriculum in Rhode Island high schools.

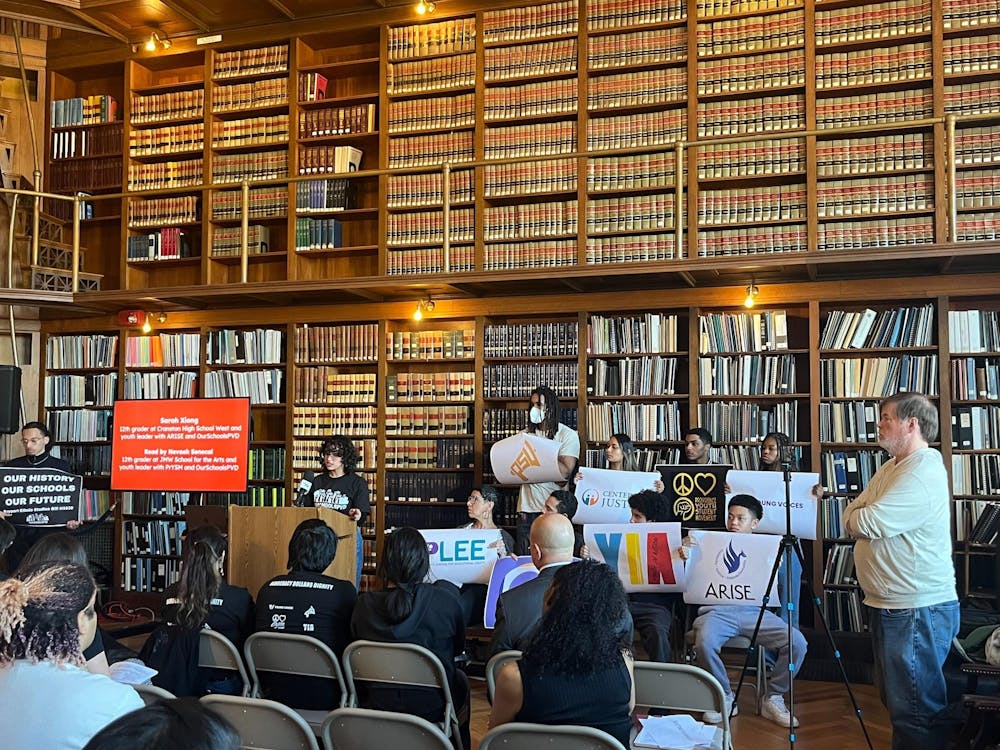

OSPVD, an alliance that advocates for educational equity in the Public Providence School District, is composed of several groups including the Alliance of Rhode Island Southeast Asians for Education, Parents Leading for Educational Equity, Youth In Action and Providence Youth Student Movement, among others.

Along with other youth organizers in OSPVD and a team of Rhode Island legislators, Espinal has worked on the group’s “Our History, Our Schools, Our Future” campaign since September to draft a bill related to ethnic studies.

The Ethnic Studies Bill would require every R.I. high school to offer a yearlong course studying state and national communities of color. If passed, ethnic studies would be a graduation requirement beginning with the class of 2030. The legislation also proposes the creation of an ethnic studies student-led leadership council to support curriculum development.

A Wednesday press conference featured speeches from local students, parents and teachers. State Representative David Morales MPA’19 (D-Providence) and City Councilor Juan Pichardo also spoke at the event. This comes after the Providence City Council voted in favor of a resolution endorsing the bill. The Providence School Board also approved a non-binding resolution to implement an ethnic studies graduation requirement last April.

“People of all different backgrounds come to live here,” Central High School junior and ARISE organizer Milia Odom said in a speech at the press conference. “People deserve to know where they come from. They deserve to know where their parents come from.”

“This bill isn’t just for the sake of having an extra class to attend,” said Community College of Rhode Island freshman and OSPVD youth leader Angel Solis at the press conference. “It’s about broadening the students’ knowledge about the importance of ethnicity and the historical background of their communities.”

Naiommy Baret GS, a Providence elementary school parent and organizer with PLEE, brought up the Trump administration’s “deliberate efforts” to dismantle public education through book bans and laws restricting discussions of identity in schools. “We are living in a time when Black and Brown histories are being erased from classrooms across the nation,” she said.

This month, a letter from the Trump administration promised to withdraw funding from schools that allow diversity, equity and inclusion programs.

“We’re not going to just back down,” Espinal said in an interview with The Herald. “We need to make a stand now because we’re actively being erased.”

The bill would allow students a glimpse into “the accomplishments and the achievements of people of color across our country,” Morales said at the press conference. “We’re not allowing ourselves to stay scared and feel vulnerable because we’re standing up and saying our history matters.”

Baret emphasized the importance of teaching history with nuance as well as “compassion and honesty.”

The bill helps ensure students “are not robbed of their histories or their voices,” Baret said.

While previously attending another school in southern Rhode Island, Adequoyah Mathews — a youth leader of Youth in Action and OSPVD — said that she faced “marginalization, daily microaggressions and racism,” given that the school was predominantly white.

This poor treatment “was enabled by the lack of diversity in both our school student body, but also in its curriculum,” she said. Adequoyah Mathews is now a junior at Met High School in Providence.

“America was built on the backbone of African Americans, yet our contributions and struggles are often altered, downplayed or skipped altogether,” said Akissi Mathews — Adequoyah’s sister — an OSPVD and YIA organizer and a freshman at the Met High School. When Black history topics were discussed at their previous school, “we felt the weight of being some of the only Black students in the class,” she added.

At the press conference, Caleigh Rockwal, a civics teacher at Hope High School and member of Providence Caucus of Rank and File Educators, emphasized the effect of ethnic studies curricula on student engagement. She said her students are more engaged when learning about diverse histories rather than white-dominated narratives.

In her speech, Adequoyah Mathews also cited a study from Stanford University, which found that ethnic studies courses significantly improved both student attendance and grade-point averages.

Morales added that this bill is “shifting the culture.”

“We’re not settling for top-down administrators to tell us what is best for our youth to learn,” he said. “We are allowing our youth to directly tell us what it is that they want to see in their curriculum.”

Annika Singh is a senior staff writer from Singapore who enjoys rewatching Succession and cheating on the NYT crossword.