As artificial intelligence rapidly gains prominence and sophistication, health care professionals in Rhode Island have been harnessing the new technology in an attempt to improve patient care. But experts have raised concerns over how to use it responsibly.

Warren Alpert Medical School Chief Resident of Dermatology Fatima Mirza — alongside her husband Rohaid Ali, the chief resident of neurosurgery at Brown University Health — is one proponent of using AI to make care more accessible for patients.

Mirza and Ali used generative AI to simplify the language of BUH’s complex surgical consent form, distilling it down to a third of its original length.

This work is geared towards helping patients who have more “issues engaging with the healthcare system, whether it be language barriers, financial barriers (or) educational barriers,” Mirza said.

She was motivated to undertake this project when treating a pediatric patient whose mother struggled to comprehend the surgical consent forms provided by the hospital.

“I thought, well, people should really have a document that they can understand and they feel is really accessible,” Mirza said. Consent forms, she emphasized, have historically been written at a reading level “equal to those of a college freshman.”

According to a 2024 paper she co-authored, “54% of Americans have a reading proficiency below the sixth-grade level.”

As of September 2023, BUH has been using the simplified form for all of their surgical procedures, according to Mirza. They are now used for around 40,000 procedures annually, she added.

Both Mirza and Ali have since gone on to help develop new medical technologies with AI. In collaboration with OpenAI, Mirza and Ali expanded a generative AI software to assist medical patients who had lost their voices. The software, known as Voice Engine, only requires a 15-second recording of a patient speaking to construct a text-to-speech program that mirrors the patient’s original voice.

“We’re really heartened by it, because it (really started) a kind of global conversation on the usage of AI in this context,” Ali said.

Atin Jindal, an assistant professor of medicine and primary care physician at the Miriam Hospital, also highlighted the diagnosis process as a potential area of innovation for AI.

“We’re talking about the ability to detect — let’s say cancer — better, faster, earlier, and that could be huge,” Jindal said.

AI chatbot and transcription technologies could also be used to lessen administrative tasks that are oftentimes time-consuming for physicians. AI, for example, has already been used to complete health insurance paperwork. This could reduce burnout and encourage physicians to be more responsive to their clients, Jindal added.

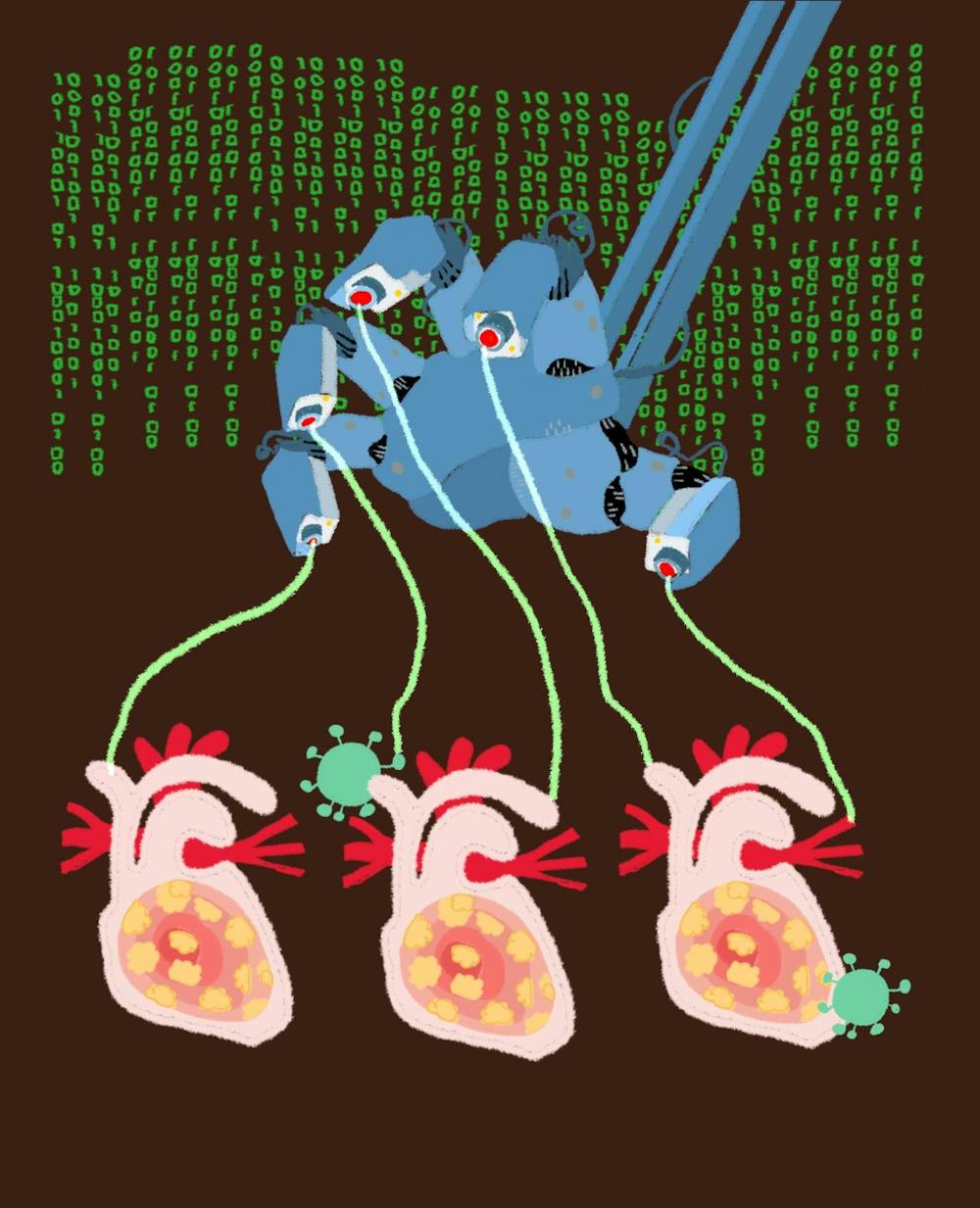

While AI presents potential benefits for the healthcare industry, some experts advise that this technology should be used and monitored carefully.

“The use of AI encourages people to gather a lot of very sensitive data,” said Michael Littman PhD’96, the University’s incoming inaugural associate provost for artificial intelligence. He warns that this data could be misused or accessed by the wrong people without proper safeguards in place.

Littman raised other issues associated with using AI, such as exacerbating medical bias. Many medical studies draw from a “demographic group (that) is very often white men of a certain age,” he added.

“Our most pressing concern is assuring that the technology is not misused,” wrote Beth Dwyer, a member of the Rhode Island AI Task Force and the director of the state’s Department of Business Regulation, in an email to The Herald.

The department published a report last year listing several areas of potential concern, including “the potential for inaccuracy, unfair discrimination, data vulnerability and lack of transparency and explainability," the report reads.

But Littman remains optimistic about the future of AI beyond just healthcare. “I love the idea that down the line … everything that we experience on campus will be hopefully enhanced by intelligent applications of AI,” he said.