Jacob Smollen

Last fall, Jonathan Fine, a lecturer in German studies at Brown, took his GRMN 0300 classes to the John Hay Library on a field trip of sorts.

They gathered in a second floor reading room, and looked over a collection of books from Adolf Hitler’s personal library, along with related materials of American and German war propaganda.

Jonathan Fine

They were, I think, shocked. They knew what was coming, obviously …

Jacob Smollen

That, of course, was Fine. The opportunity to see the books was part of his initial pitch to prospective students during shopping period. He saw it as a unique application of the language and a way to engage with some of the course’s units on German history and the Holocaust.

Jonathan Fine

You know, I know students 20 years down the line, they may not remember how to conjugate many verbs in German, but they will remember holding Hitler’s copy of “Mein Kampf.”

Jacob Smollen

Despite the morbid subject matter, several students stayed after the class ended.

One of those students was Olha Burdeina ’27, a second-year student from Ukraine. Burdeina said she saw connections between the propaganda found in Hitler’s books and related materials and the current war and Russian propaganda about her home country.

Burdeina felt excited about the prospect of examining the books in class, but …

Olha Burdeina

I also felt kind of uncertain whether I want to see that, because what is happening right now in my country, in Ukraine, is really, really related to what was going on in those times with propaganda and manipulation.

They were also written by people and, like, put together by people who believed in that propaganda and that kind of machine and that regime, and that really scared me, because I feel like, whenever I was touching the book, I was a part of it.

Jacob Smollen

Burdeina isn’t the first person to have complicated feelings about the collection. There are roughly 100 items, by the way, most retrieved from Hitler’s underground Berlin bunker following his suicide.

In interviews for this story, sources told me they felt a range of emotions when interacting with these materials, from excitement at investigative potential, a general ickiness, to, well … nothing.

Burdeina’s experience also gets at a central question about the books, and their place at Brown. Amidst all these mixed emotions, what do they really have to offer?

I’m Jacob Smollen ’25, a podcast editor for the Bruno Brief. In this podcast episode, we’re talking about Brown’s little-known acquisition of books from Hitler’s personal library and the debate over what these books can or cannot tell us about one of the most reviled people in human history. Plus, what do they tell us about collecting at the Hay?

But, before we get into those questions. Let’s take a few steps back, at least historically.

Gwendolyn Collaço

So basically, Colonel Aronson was an American official who had been allowed by his Soviet colleagues to take a number of books from Berlin …

Jacob Smollen

That was Gwendolyn Collaço, the Anne S.K. Brown Curator for Military and Society of the Hay’s Special Collections Department. She’s beginning to describe the man at the center of the journey of these books to Brown — Colonel Albert Aronson.

In May 1945, after Adolf Hitler’s death …

Archival Audio

And this was Berlin, a city in name only.

Jacob Smollen

… Aronson — an American soldier — found himself in the former German dictator’s underground Führerbunker in Berlin. The Soviets had beaten him there, and already taken many of the items they wanted, but they let Aronson leave with books and photographs.

After his death roughly 40 years later, these same books were dug out of his attic and donated to Brown by his nephew, a Brown alum.

In addition to these books, Brown also has a couple magazines from Hitler’s Berchtesgaden residence found by Quentin B. Leonard ’44, another U.S. service member. Although Leonard wrote in an August 1945 letter to Professor Raymond Archibald that the materials were “totally worthless, except for their souvenir value.”

Quentin B. Leonard’s ‘44 letter to Professor Raymond Archibald explained that he believed the magazines he’d gathered from Hitler’s residence were “totally worthless, except for their souvenir value.”

In 2020, Brown also acquired 17 titles retrieved from Hitler’s Munich apartment by Lieutenant Craig Hugh Smyth as part of a donation by his son.

Combined with 1,200 titles at the Library of Congress, which is the other major collection of Hitler’s books in the U.S., the books only represent less than a tenth of what was Hitler’s total library.

But, what exactly is in the books at The Hay?

Here’s Collaço again.

Gwendolyn Collaço

Some of the themes are ones you would expect. So you have books that include national poems and literature, German history, heraldry, genealogy, all these things that kind of built up this national identity.

Jacob Smollen

There’s also Nazi propaganda, including texts on the origins of the swastika and works related to elements of statesmanship like economic policy. But then there’s these …

Gwendolyn Collaço

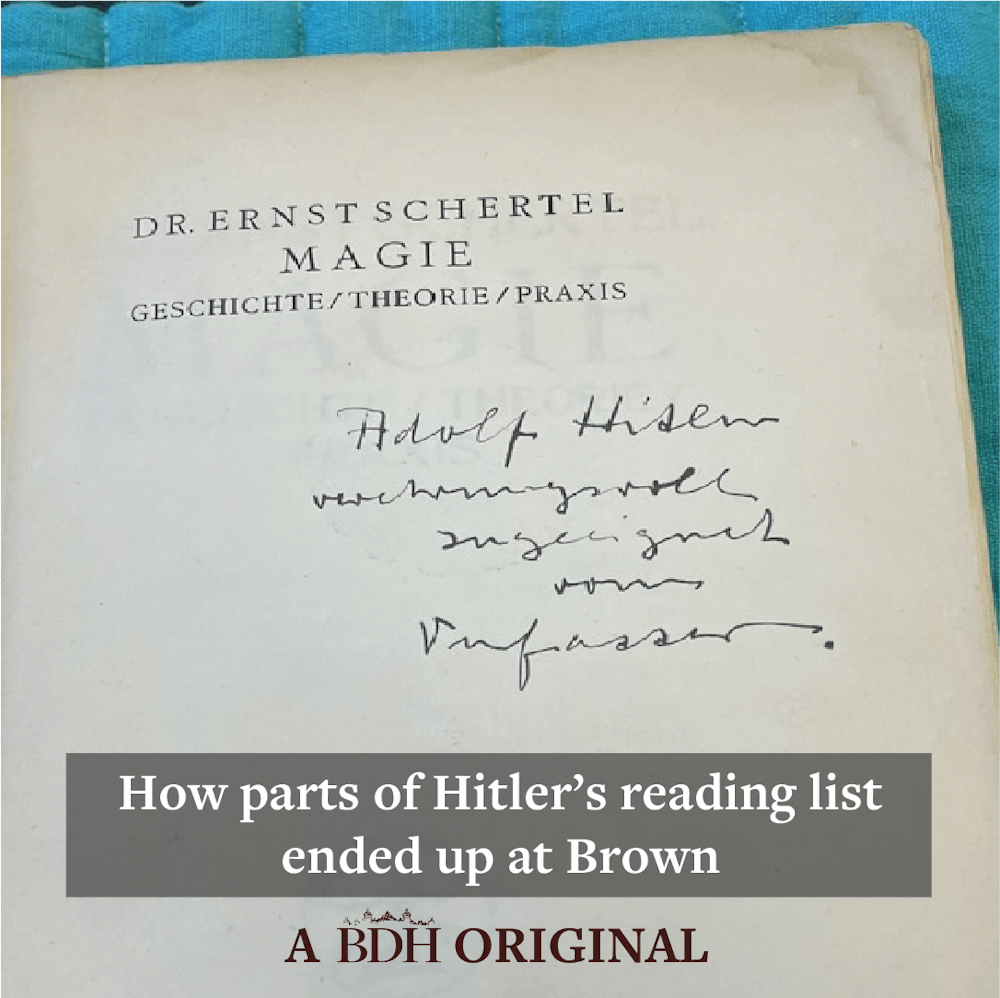

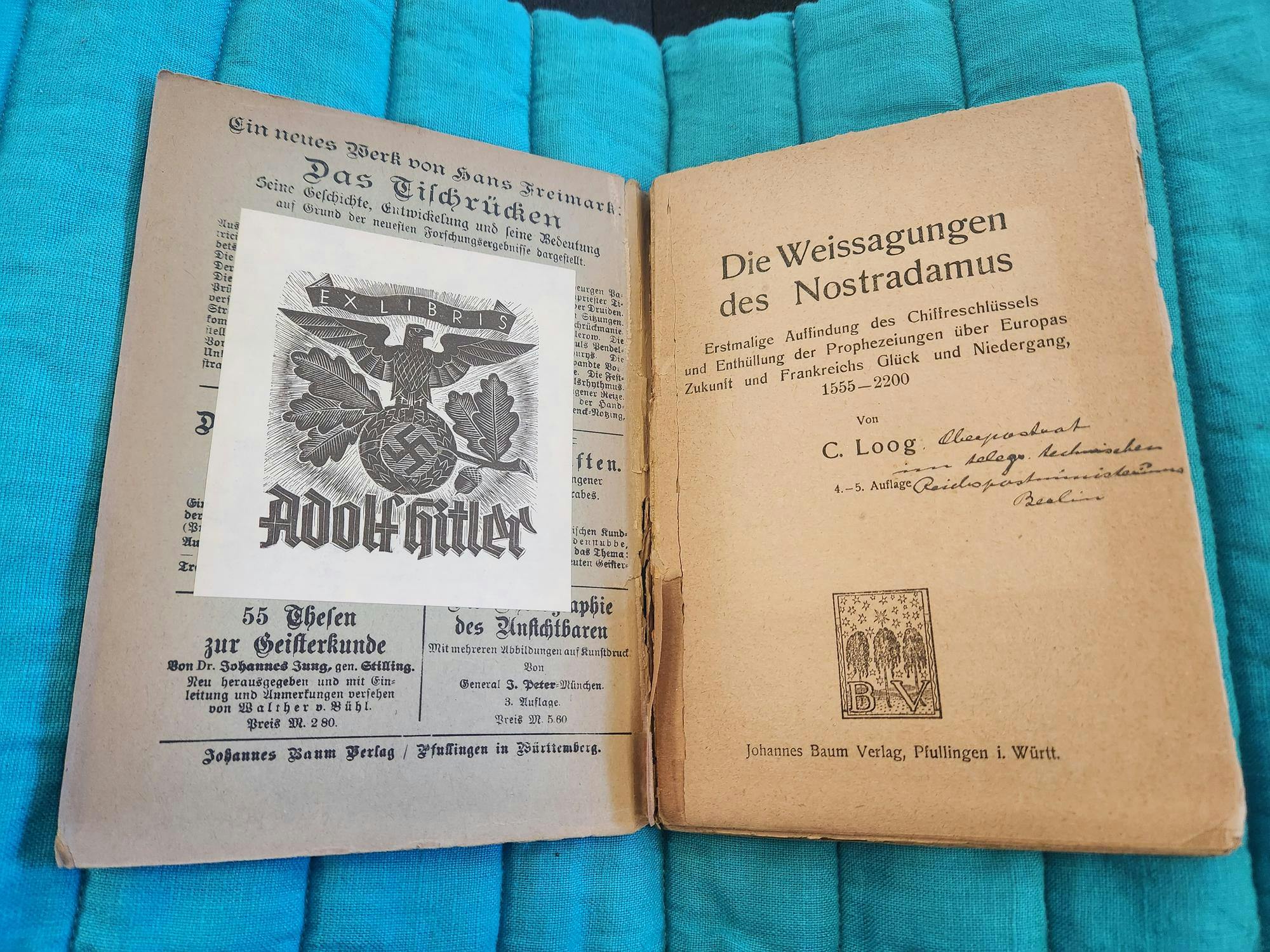

Books on the occult and supernatural, like “The Prophecies of Nostradamus” and books on the practice and theory of magic. Things that I had not expected to go into this collection finding, and I don’t think many people do.

The Prophecies of Nostradamus was one of several books related to the occult owned by Adolf Hitler which now belong to the Brown Library.

Jacob Smollen

These volumes include “Magic: History, Theory, Practice,” which is one of the most annotated books in the entire collection, according to historian Timothy Ryback, who studied the collection for his own book, titled “Hitler’s Private Library.”

Still, the books haven’t gotten much academic attention. Collaço told me that in the past four years the library has received six inquiries for the books. The number is quite low compared to more popular collections, she said.

That leads to the next important question here. If interest is low, why do these books matter?

The answer is a bit of an open question. A lot of it boils down to marginalia. These are the marks or notes made in the margins of books or other documents. The librarians I spoke with at the Hay said that the lack of marginalia in these books, as well as the fact that many of these texts were gifted to Hitler rather than purchased by him, means they have relatively little to say about the dictator.

Collaço makes the case that since the Soviets took most of the books from Hitler’s personal library, the collection at Brown is one of “happenstance,” and a small one at that.

Gwendolyn Collaço

What sticks out to me is that most of them are not selected by Hitler, as in, sought out by him. They’re actually mostly gifted to him by either the authors or by friends or they’re presentation copies that people gave to him in an official capacity, which I think kind of changes our perspective of like, how we perceive of this collection, because I think if someone builds a collection thoughtfully and intentfully … in order to actually create a cohesive collection, it looks different than if it’s a collection that was brought together out of works that were being sent to him that maybe he would not have necessarily bought for himself.

Jacob Smollen

Certain volumes were also left essentially unopened and Collaço found limited markings in her examination of the books.

Gwendolyn Collaço

The most I’ve seen are these kind of red or pencil or crayon lines in the margins that kind of emphasize a section. So I’ve never seen an actual note in the marginalia that was definitively in Hitler’s hand. And so we’re guesstimating, hypothesizing that these red marks are from Hitler, and they are not on all the books by the way, they’re only on a few.

Ryback says the underlined sections in some of Hitler’s books are the same ideas appearing in his speeches. Collaço says it’s impossible to prove the markings are from Hitler himself.

Jacob Smollen

She suggested rather than looking at this as an opportunity to gain insight into Hitler’s mind, it might instead be a window into those around him.

Gwendolyn Collaço

The vast majority of annotations we have are those dedicatory notes from the people who gifted it. So I think you can get a sense too about like, how well they knew him, are they using like, the formal “Sie” versus like the more informal “Du” to refer to him and things like that.

Jacob Smollen

Here she’s referring to the two different forms of the second person in German.

Gwendolyn Collaço

So there are these little clues, so you can really begin to piece together, actually a social network of how books circulate, like the gift economy of books. And I think that is how I would approach it, versus it being a reflection of one collector’s mind.

Jacob Smollen

I also spoke with Heather Cole, she’s the head of special collections instruction and the curator of literary and popular collections at the Hay. She’s worked to bring important collections like the papers of Joy Harjo to Brown. Harjo was the 23rd U.S. Poet Laureate, the country’s first Native American to serve in that position.

Heather Cole

In any kind of library or museum, you have collections that are problematic, you have collections that have been here a long time, or that you wouldn’t accept this point, but sort of figuring out how to properly and responsibly steward them in the present is something we think about a lot.

Jacob Smollen

She told me that there are a variety of criteria for determining which new collections the Hay takes on. Curators have to think about gaps in the library’s current holdings, the condition of the materials, as well as whether it will reflect the communities that call Brown home.

Cole acknowledged there’s potential to learn about famous, or in this case infamous, people through the books they owned, and their marginalia. But, today, if Hitler’s books were offered to her, she wouldn’t take them.

Heather Cole

Hitler’s a person that I’m like, do, do we, do we need to know that? So that’s just like me personally.

Jacob Smollen

Collaço left the question of whether she’d collect the same books today open-ended, but emphasized that the library would approach that decision differently than it would’ve in the past. She echoed many of the same criteria mentioned by Cole.

In that sense, the reflection out of all of this is less about historical importance, and instead about how the collections of the Hay and archives more generally have evolved.

Gwendolyn Collaço

It might also just show the direction of the trends in research, which are moving away from these kind of great men histories, towards other types of perspectives in these historical moments, and I know certainly with the rest of our collection, that’s what we’ve been trying to do, is really bring in some underrepresented voices, rather than focus on those that have gotten the majority of attention already in scholarship.

Jacob Smollen

But given the case against, let’s get into why these books might be relevant after all.

Ryback, who I mentioned earlier, believes that these books and the marginalia contained in them are a means of learning about the secretive mind of Adolf Hitler. The ideas found underlined in some of these books are the same ones later appearing in Hitler’s speeches, Ryback said. They also offer insight into Hitler’s interest with spiritualism and the occult.

Timothy Ryback

When we say to ourselves, oh, my God, where did this evil come from? How could this man, what was he thinking? What was going on in his mind? These really are records of Adolf Hitler in his most private moments. With marginalia, you’re not lying to anybody, you’re not spinning anything.

In a service to history, in a service to historians and scholars, you — it would be unthinkable that you wouldn’t take this collection and value it for its historical value …

Jacob Smollen

Ryback also claims to have dealt with some of the questions around the marginalia’s authorship. In the early 2000s, he tracked down Hitler’s former private secretary, Traudl Junge, attempting to prove that these lines had indeed come from Hitler.

Timothy Ryback

The Brown library had kindly photocopied pages with the marginalia, and I was able to show them to Traudl Junge, and I asked her two questions.

Jacob Smollen

Those questions included whether the marginalia was consistent with what has been found at the Library of Congress. The answer was yes. And secondly, if the marginalia was consistent with the secretary’s memory of Hilter and his attitude towards reading.

“Absolutely,” she told Ryback.

Timothy Ryback

Then I asked her another question. I said, Could you help explain to me, or can you explain to me why we have so many books on the spiritual, on the occult, on the other worldly? And she said, in her year and a half, two years with Hitler as secretary, she said he would read late into the night. She used to have breakfast with him every morning. He would come down, it was always a late breakfast, and he would always recount, you know, his previous night’s reading to her endlessly. It was a monologue. But she said he was preoccupied with these higher forces in the world, and that these books reflect his preoccupation with this.

Jacob Smollen

Still, Ryback does acknowledge that the gifted books in the collection are in a separate, less relevant category. But, he said there are between 10 and 15 books at Brown that were clearly acquired by Hitler himself.

Similarly, he knows not all connections check out. Ryback once discovered a book in the Brown collection contained a prophecy foretelling a great German leader that would unify the people and lead them into a second World War.

When he arrived to look at the copy on campus, he discovered Hitler had never read the passage.

Ryback also said that while he approached the books from a forensic angle, he understands the horror that people might feel when handling these materials. Yet, he worries about the types of people who gravitate to these items when academics don’t.

Timothy Ryback

When you say should we at Brown even have this? I said, thank God they’re at Brown, because I actually know some of the places they may have ended up if they weren’t. And I also think as toxic as they may be, as unsettling as it may be to have those sitting next to the Audubon folios, I think one can’t overemphasize the historic importance of having those for understanding the man, but also their place in 20th century history.

Jacob Smollen

Wherever he encounters these books out in the world, Ryback encourages people to donate them to Brown or the Library of Congress. In fact, he said he knows the owner of the last book Hitler was reading before his death — a biography of the former Prussian King Frederick the Great.

He’s still trying to convince them to turn the book over to Brown, if they’ll take it. If not, he said maybe the Library of Congress will.

Timothy Ryback

I’m not saying it’s going to redefine our understanding of the man, but I think it does offer and provide important insights into the most evil personality of the 20th century.

Jacob Smollen

That’s it for this episode of the Bruno Brief. This episode was produced and edited by me, Jacob Smollen ’25, with help from Irene Zheng ’28. If you like what you hear, subscribe to Brown Daily Herald podcasts wherever you like to listen and leave a review. Thanks for listening.

Audio Credits

Denzel Sprak, courtesy of Blue Dot Sessions

The Summit, courtesy of Blue Dot Sessions

Within the Garden Walls, courtesy of Blue Dot Sessions

Ervira, courtesy of Blue Dot Sessions

Archival Audio, Creative Commons License reuse, courtesy of National Archives

Jacob Smollen is a Metro editor covering city and state politics and co-editor of the Bruno Brief. He is a junior from Philadelphia studying International and Public Affairs.