Using data from 638,999 patients, a new study by a research team at the Warren Alpert Medical School found that the incidence of cervical and thoracic spinal fractures has increased since 2003.

The data came from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System, which collects information on all emergency room consultations and admissions in the US, according to Alan Daniels, a professor of orthopedics and the spine division chief.

In recent years, spine specialists noticed that more and more patients were coming to the emergency room with fractures, Daniels said.

But “there wasn’t a lot of data out there to say what the incidence of spine trauma was,” medical student and first author Mariah Balmaceno-Criss MD’25 pointed out.

To remedy this gap in literature, the team looked at data from emergency department visits reported to the NEISS between 2003 and 2021. They then grouped the data by type of fracture and the patients’ demographic information, Balmaceno-Criss explained.

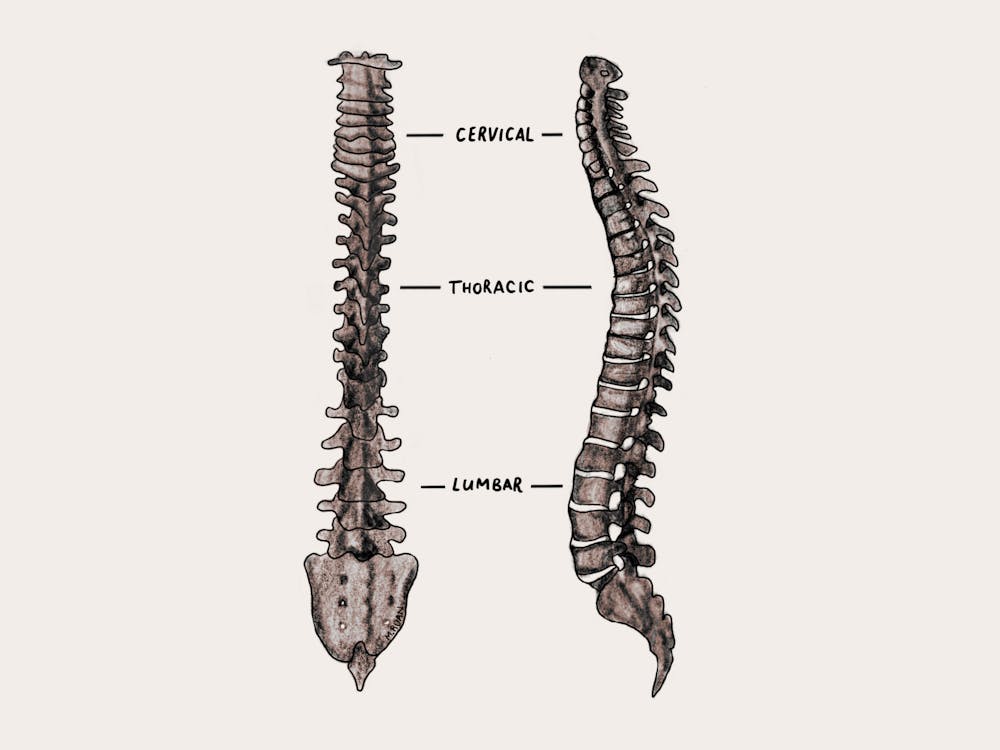

The study focused on vertebral fractures of the cervical and thoracic spine — the two upper-most regions of the spine. A vertebral fracture is a break in one of the “bony units” of the spine, which can cause neurological deficits ranging from loss of motor function to full paralysis, according to Bassel Diebo, an assistant professor of orthopaedics.

According to Diebo, these fractures can be classified into high- or low-energy fractures based on the mechanism of injury. While high-energy fractures are caused by forceful collisions in events like motor vehicle accidents or high-impact sports, low-energy fractures can occur from minor incidents at home, such as a fall from standing height.

Daniels noted that the incidence of low-energy spinal fractures is “generally” increasing, while that of high energy fractures are not. Because low-energy fractures often occur in the aging population, especially those with osteoporosis — a disease classified by weakening of bones — Daniels said “it’s really just an increase for the elderly population.”

As people age, their bones weaken. Daniels suggested, then, that incidence of spinal fractures may be increasing because “people are living longer and staying more active.” Physicians also now have better technology to diagnose even minor fractures.

Given this result, the study proposed more efficient osteoporosis screening as a next step for clinicians to minimize the risk of low-impact fractures.

Daniels labeled osteoporosis as “one of the most poorly-managed chronic diseases of the elderly,” encouraging screening and treatment for affected patients.

Currently, only women 65 and older are screened for osteoporosis, but screening younger patients could lead to protective and preventive care, according to Diebo.

Keeping the elderly population active — such as through physical therapy — could also “help prevent falls and help them stay steady on their feet,” Daniels said. Since the team found that many fracture-causing falls happened at home, Daniels also suggested an increase in “social support and safety” for the elderly population.

Bryce Basques, an assistant professor of orthopedic surgery, who was not involved with the study, said the researchers used “the perfect data set.”

“It’s a very well done study,” Basques said. “You want a broad, representative sample of all the fractures across the entire country, and then you want to essentially describe what’s happening with these fractures.”

Using funding from the Brown-endowed Chirico Family Grant, the team is now “trying to determine the safest and least invasive, but most optimal treatment possible to optimize their spinal alignment and function,” Daniels said.

Francesca Grossberg is a staff writer covering Science and Research. She is a sophomore from New York City studying Health and Human Biology.