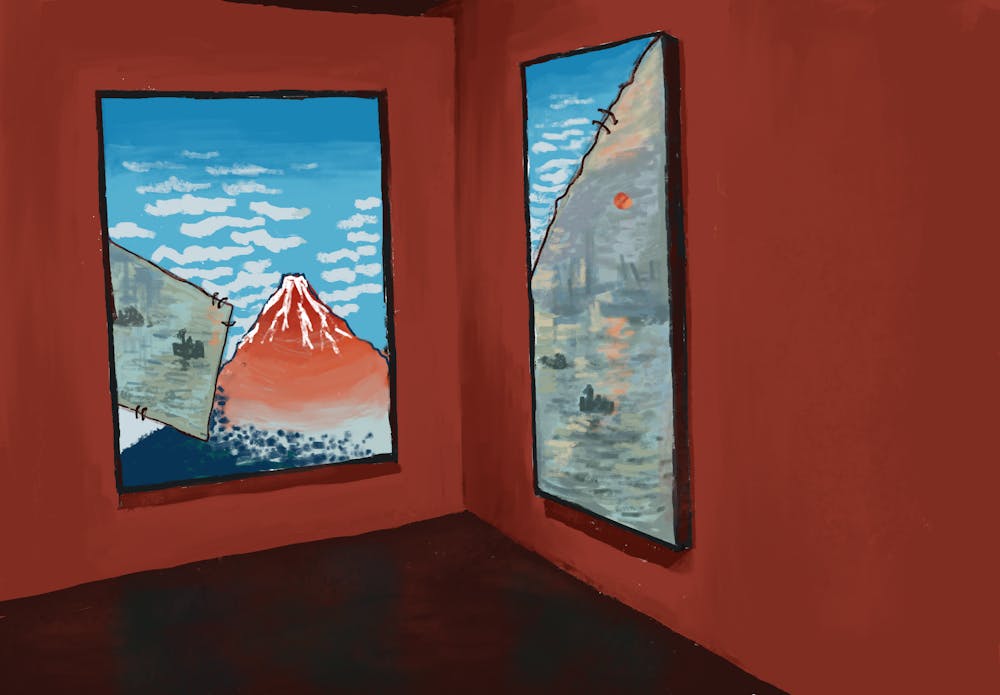

During the 18th and 19th centuries, Japanese art, Impressionism, and other European art styles were heavily linked. Ukiyo-e woodblock prints, created to depict “The Floating World of Edo” (modern-day Tokyo), were mass-produced for the enjoyment of commoners from the 17th century to the early 20th century. These prints show aspects of contemporary life and serve as Japanese culture ambassadors for the wider world. Their influence spread to later European art movements like Impressionism and Post-Impressionism.

In response to the modernization of Paris during this time, Monet and the Impressionists focused on exploring the celebration of the pleasures of middle-class life. He tended to explore these pleasures under different light and weather conditions to create his varying series depicting the atmosphere and environment.

Together, Japonisme and Western Art heavily influenced each other and tended to portray similar themes of pleasure and leisure during this turn to modernism in the 18th and 19th centuries.

In the bustling city of Edo, commoners would frequent the Yoshiwara pleasure quarters, watch kabuki theater, and spectate sumo competitions. Utagawa Hiroshige’s One Hundred Famous Views of Edo: Moon-Viewing Point shows one of many brothels or inns in the Shinagawa settlement. The serene interior looks out the open window at the rising moon during August, encapsulating the peaceful lifestyles of the Japanese geisha. The bonsai trees and pots of leaves in these prints of the interior also suggest a meditative atmosphere as the entertainers settle in for the night after work in the pleasure quarters. Another leisure activity, kabuki theater, is showcased in Torii Kiyotsune’s piece, The interior of a Kabuki theater. As it was one of the greatest delights of the commoners, men and women would actively engage in kabuki performances, responding to actors with praise and clapping. The levels and height of the theaters show the packed and lively nature of this form of entertainment.

Despite the strong contrast in the style of artwork, Impressionism also pioneered an idea of leisure and pleasure in the French countryside through the style of broken color and rapid fragmented brushstrokes. The similar idea of capturing middle-class life pleasures, la vie moderne (“modern life”), is prominent in works such as Woman Reading by Édouard Manet. In this scene, the free brushstrokes and light colors depict a cool, relaxing day at a Parisian café, where artists and writers would gather to observe the new urban setting. Similarly, Claude Monet’s famous Water Lilies series also portrays an atmosphere of serenity, peacefulness, and leisure of the middle classes through the implementation of open composition, with the large lotus pads and lilies suspended as if in a space beyond the frame. This major piece of landscape art contributed to Monet’s exploration of a radical view of nature, focused on capturing this fleeting moment of pleasure and desire. Moreover, his private Japanese garden that he constructed in Giverny, the garden depicted in Water Lilies, was thought to be created for contemplation and relaxation.

As we discuss Monet’s work, the influence that Japanese art and culture had on him becomes evident. In the late 19th century, the popularity of ukiyo-e prints was seen as an indication of knowledge, taste, and wealth. Monet was heavily influenced by Japanese ukiyo-e artists, especially Katsushika Hokusai, who would shake up his creative process. He collected Japanese woodblock prints and would compile them in his home in Giverny. He first discovered Japanese prints in 1862, and the decorative, flat media had a strong influence on the development of modern painting in France. Japanese influence is directly reflected in his Water Lilies. The colossal size of the paintings and the inclusion of the Taiko-bashi Bridge, closely tied to Hiroshige’s In the Kameido Tenjin Shrine Compound, give off a sense of calm and purity characteristic of Japanese prints. Hokusai and Hiroshige's flower prints may have also been a factor in Monet's love for water lilies.

The impact of Japonisme is also seen in other art movements across Europe. The bright, vivid colors and the attention to the passing of time influenced Impressionism, and Hiroshige’s bold lines representing trees and flowers had a strong influence on Art Nouveau artists. Hiroshige's One Hundred Famous Views of Edo had a considerable impact in Europe because of the vivid colors and unconventional perspectives. Artists such as Vincent van Gogh were influenced as well, most obviously in his Almond Blossom derived from Hiroshige's Plum Garden at Kameido.

On the other hand, Impressionism also heavily influenced Japanese art and Hiroshige. Japan allowed more Western imports after opening up in the mid-19th century and also looked to incorporate Western styles such as atmospheric perspective and linear perspective, which Hiroshige famously uses in multiple of his works. The Japanese public’s taste also gradually changed. Knowledge of Western industry and the opportunities it offered became more widespread in Japan, so the public outcry for novel ideas grew. The Japanese were starting to produce and consume Western-style art in preference to traditional ukiyo-e art. An example was the artist Kuroda Seiki (1866-1924), who was known as the father of modern Western paintings in Japan. After studying in France with Raphaёl Collin (1850-1916) for 10 years, he brought home the techniques of Impressionism and plein-air painting to depict famous local sights, geisha, and neighborhoods. His work, By The Lake, showcases his attempts at fusing Impressionism with traditionally Japanese subjects. He brought about new attitudes towards landscape paintings, liberating the stereotyped famous scene landscapes that were key in Edo periods and instead creating vivid, lively depictions of ordinary scenes in nature. Another example is his work, Landscape (Chigasaki Seaside), that resonated with Impressionist artwork in France. Kuroda also introduced many other new techniques and materials to the Japanese art world and was one of the key figures in driving the public’s taste away from the traditional art of ukiyo-e in Japan during the late 19th century.

Thus, both Japanese art and European art heavily influenced each other, particularly evident when viewed through the lens of pleasure and leisure, which were both very prominent during the 18th and 19th centuries in their respective environments and cultures.

Kuroda, Seiki. By the Lake (湖畔), 1897, oil on canvas, 69 x 84.7 cm. Tokyo National Museum.

Kuroda, Seiki. Landscape (Chigasaki Seaside), 1907, oil on canvas, 25.5 x 34 cm.

Monet, Claude. The Water-Lily Pond, 1899. Oil on canvas.

Hiroshige, Utagawa. One Hundred Famous Views of Edo: Moon-Viewing Point, 1857. Woodblock print.

Manet, Édouard. Woman Reading, 1880-1882, 61.2 × 50.7 cm. Oil on canvas.