For two decades, Janelle Monáe has tipped on a tightrope toward mainstream success, yet she has seemingly never been able to fully break out commercially. As a result, very few people are aware of her ongoing multi-album science fiction saga Metropolis, which has been over 20 years in the making. Inspired by the 1927 German silent film of the same name, Monáe has been slowly weaving together an intriguing, sometimes confusing story of romance, oppression, and resistance under totalitarian control, split across four concept albums. The lore of this world goes deep, with many unanswered questions prompting fans to speculate how each subsequent project connects to the greater Metropolis narrative.

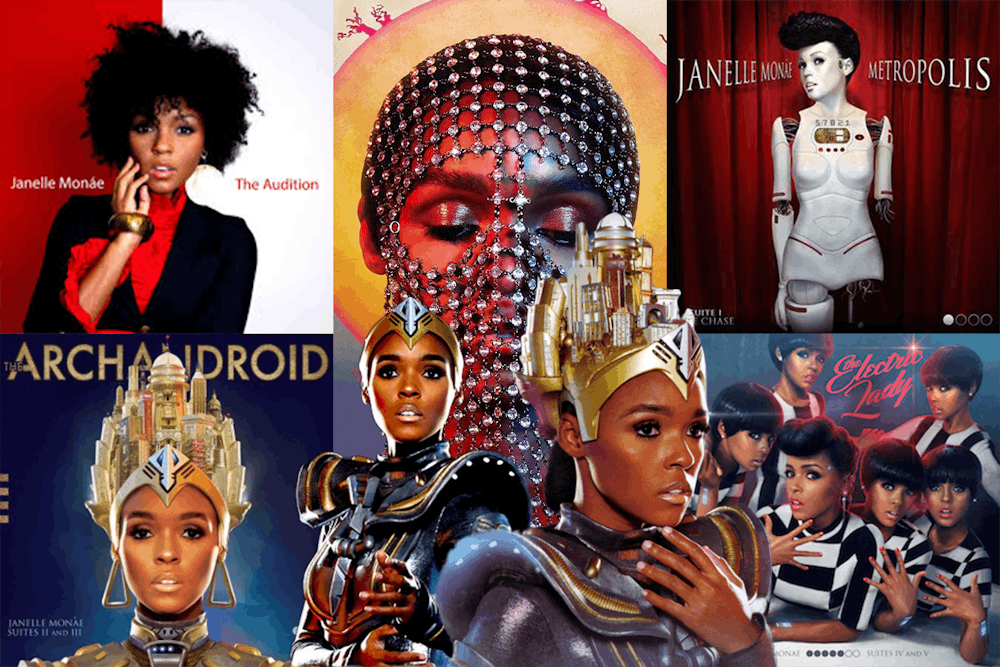

The Audition

If you’ve only listened to Janelle Monáe’s work through streaming platforms, you may be surprised to learn about her 2003 demo album, The Audition. “Metropolis” and “Cindi”—tracks four and five of this self-released project—are the beginnings of the Metropolis saga. “Metropolis” introduces the “Star Core Metropolis” from the perspective of a cyber girl living on the “wired side of town” who falls in love with a man named Anthony Greendown. She describes the oppression under which she lives, both socially and under the tyranny of a force called “Droid Control,” writing, “And it’s a common thought / That wired folk can be sold and bought,” and “One nation under a microchip / Neon slaves, electric savages.” These direct references to slavery are an early example of Monáe’s Afrofuturism, a perspective on science fiction shaped by Black histories and experiences.

In a 2013 article from The London Standard, Monáe discusses android oppression in her work, stating, “I speak about androids because I think the android represents the new ‘other’. You can compare it to being a lesbian or being a gay man or being a black woman...What I want is for people who feel oppressed or feel like the ‘other’ to connect with the music and to feel like, ‘She represents who I am.’” This representation of Monáe’s intersectional identities, as a Black pansexual and nonbinary person using she/they pronouns (which she would reveal publicly in 2018 and 2022), are affirmed by the track “Cindi.” This song introduces the character of Cindi (who would later become Cindi Mayweather) as a mirror-image alter-ego of Janelle Monáe, a persona she yearns to become.

Metropolis: The Chase Suite

Monáe’s 2007 EP Metropolis: The Chase Suite acts as the official “Suite I” of IV in the Metropolis saga (later expanded to VII with the release of Electric Lady), taking a theatrical approach to the genres of R&B, funk, and soul behind its musical storytelling. This project expands upon the story of Cindi Mayweather, who is now scheduled for immediate disassembly and on the run from Droid Control-ordered bounty hunters for the crime of falling in love with a human, Anthony Greendown.

The project’s third song (and the only one to receive a music video), “Many Moons,” introduces time travel into Metropolis, suggesting a less linear view of the overarching project. The video depicts the “Annual Android Auction,” a gathering of androids and non-androids, many of whom are depicted by Monáe herself. The song ends with a spoken word “Cybernetic Chantdown,” in which various real-world and Metropolis-specific topics of note are listed, such as, “Civil rights, civil war / Hood rat, crack whore,” and “White house, Jim Crow.” These parallels transcend the diegetic world of Metropolis and expand Monáe’s fictional reality, in which she herself plays a narrative role. In a 2009 interview with Kurt Andersen, Monáe reveals that in the Metropolis universe, “Janelle Monáe actually, in 2719, worked in a superhero surplus store and she was thrown back into 2007, but before they threw her back, the Snatchers cloned her body and Cindi Mayweather has her DNA.” This self-insert of Monáe into the greater narrative of Metropolis opens infinite possibilities into how the tale of Cindi Mayweather can be read, yet illustrates the congruent needs for resistance against oppression in all worlds—in the world of today, in the world of 2719, in many worlds with “Many Moons.” In all worlds, Cindi Mayweather is a symbol of revolution, a persona that transcends the confines of time and space.

The album’s narrative conclusion implies that Cindi has been captured and disassembled. The song “Cybertronic Purgatory” offers a haunting, operatic call for the one she loves, singing, “This stormy sunrise / Will die / And I’ll be with you / My love, my love.” Still, with the nature of clones, android DNA replication, and even time travel, there exists hope that Cindi Mayweather will triumph over her captors and someday return…

The ArchAndroid

…And she does return only three years later in The Archandroid, representing Suites II and III of the Metropolis saga. As it was technically her debut album, Monáe was tasked with continuing the Cindi Mayweather narrative while refining her own musical style and abilities, which she does incredibly successfully. Cindi Mayweather is now revealed to be the ArchAndroid, a messianic figure whose return to Metropolis has been prophesied by the Book of Zoman to bring androids freedom from the control of a secret, time-traveling society called the Great Divide. Each suite begins with a dramatic orchestral overture (reminiscent of Lady Gaga’s Chromatica interludes) and continues to discuss many of Monáe’s oft-explored themes.

Suite II begins with “Dance or Die (feat. Saul Williams),” which calls back to “Many Moons” through its spoken word introduction. Lyrics such as “We’ll keep on dancing till she comes” reference the oppressed androids who await the foretold return of the ArchAndroid, with dancing as a form of resistance. The subsequent three tracks, “Faster,” “Locked Inside,” and “Sir Greendown,” continue the narrative’s themes of captivity and yearning for escape. These songs precede tracks that discuss dance as analogous to revolution and themes of war, culminating in the music video for “Tightrope (feat. Big Boy)” which directly addresses these themes by depicting Monáe and others dancing through an oppressive facility.

Suite III concludes the album with sweeping, experimental tracks, mostly focusing on Cindi Mayweather’s desires to escape to this world’s version of Nirvana, a paradise referenced by many names throughout tracks such as “Wondaland.” Still, Mayweather remains separate from her lover, as the song “57821 (feat. Deep Cotton)” announces, “Anthony Greendown your Cindi Mayweather / Will always be waiting for you.” The album concludes with a nearly 9-minute track titled “BaBopByeYa,” a track originally written in 1976 that now acts as a special call to Anthony Greendown to signal Cindi’s safety and location.

The Electric Lady

Monáe’s second studio album, the 2013 The Electric Lady, is a prequel to the rest of Metropolis, but confusingly also Suites IV and V. Monáe decided to expand the number of Suites from the initial IV to VII, leaving room for a future finale to the Cindi Mayweather saga. Unfortunately, this album remains the most recent installment of Metropolis, leaving fans to hope that they may one day receive a proper conclusion, now over 10 years since the album’s release. Still, the project offers a myriad of innovative songs that continue to flesh out Monáe’s complex world.

The album’s tracks are interrupted by frequent radio-style interludes which feature banter led by host “DJ Crash Crash,” often focusing on music sensation Cindi Mayweather and her efforts to evade authorities whilst performing pop tracks like “Dance Apocalyptic” to the denizens of the android underground. In this manner, the entire album takes the form of a radio set, with a structure reminiscent of Beyoncé’s recently released Cowboy Carter. The album particularly focuses on queer love, with a radio caller declaring on the track “Our Favorite Fugitive - Interlude” that “Robot love is queer!”, an extension of Monáe’s continued android metaphor. Finally, the project includes numerous notable collaborations with artists such as Prince, Erykah Badu, Solange, and Miguel, cementing the album as a truly historic culmination of musical talent, ingenuity, and Afrofuturist imagination.

Dirty Computer

By far her most streamed album to date, 2018’s Dirty Computer marks a departure from the Cindi Mayweather saga. The album is more grounded, directly addressing real-world topics of sexuality, American ideals, and racial violence. In the album’s accompanying film of the same name, Monáe plays Jane 57821, a citizen of a society that seeks to label differences as making one “dirty,” eliminating queerness and expression through the “cleaning” of memories.

While existing outside of Metropolis, Dirty Computer possesses several thematic parallels to the story of Cindi Mayweather, including the decision to represent both characters with the very same number. Whether diegetically connected through some unexplained reasoning or not, both stories present Monáe as a complex, intersectional member of a broken world, one that seeks to suppress the joys of authentic self-expression. In this manner, Cindi Mayweather IS Janelle Monáe, and so is Jane 57821. These aspects of Monáe’s existence—artistic projections of her struggles, dreams, and desires—are frames through which the audience may choose to view the complex, interconnected worlds that Monáe has constructed. Monáe calls on us, the viewer, to don the persona of Cindi Mayweather in the face of our adversities, and against any and all obstacles to our freedoms. As she concludes The Archandroid, “I see beyond tomorrow / This life of strife and sorrow / My freedom calls and I must go / I must go / I must go / I must go.”