For all its faults, I can’t help but love the TikTok algorithm. Each evening, it thoughtfully selects heartwrenching sapphic media and drops them into my eager palms with care and restraint—feeding me just enough that I’m hooked, but not so much that it feels forced. Just enough that I can tell myself that I’m consuming these “thought pieces” organically.

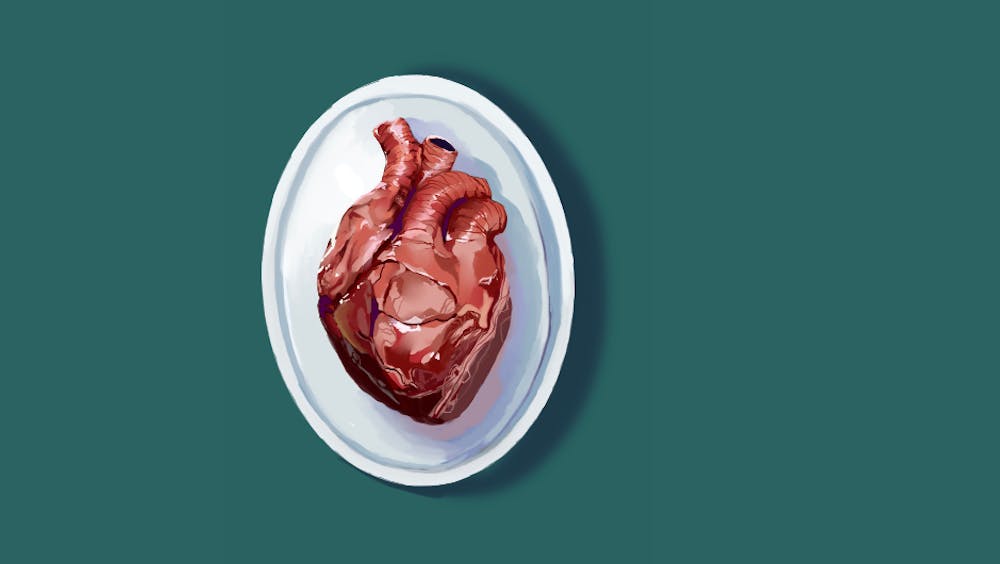

So maybe the algorithm was off its game when I started to notice a proliferation of collage slideshows and edits about “cannibalism as a metaphor for love.” It’s packaged the way TikTok pseudophilosophy always is: PNGs of vaguely aesthetic images pasted on a crinkled paper background, with a paragraph written in all-lowercase, serif font.

Referencing popular closet-lesbian media like Showtime’s Yellowjackets and 2009 cult classic Jennifer’s Body, these slideshows claim that the theme of cannibalism between girls in media is allegorical of love.

User Fei on Medium explains the connection well: “Love, like cannibalism, can be consuming and all-encompassing. It can make us lose ourselves in the other person, to the point where we feel as though we are being consumed by them.”

Yet, I don’t believe the pioneers of literary cannibalism ever meant for it to be an allegory for love.

It's an inherently one-sided act of consumption, where one entity engulfs another entirely. The corpse cannot protest. That’s not love. When consuming someone, the act is selfish—one person absorbs and effectively “erases” the other, which is antithetical to the respect that love involves.

Cannibalism is the most stomach-churning version of possession.

In the TV show Yellowjackets, the protagonist Shauna’s eyes fill with hesitation as she struggles with whether to eat her ex-best friend Jackie’s frostbitten ear. The choice she’s contemplating is not whether to love Jackie. That’s been established. Rather, in swallowing that ear, feeling it slide down her throat along with centuries of cultural taboo, Shauna made the choice to possess the unpossessable. When Jackie was alive, their friendship (relationship?) was far too fractured to stomach this radical unity. But through cannibalism, she made the decision that Jackie’s posthumous body belonged to her.

This logic of possession may also explain why cannibalism is a popular trope in sapphic media. Rhetoric around female sexuality lacks conquering language: We are always penetrated, deflowered, objectified. Never is heterosexual sex framed as a female partner engaging in the act of “engulfing”—female anatomy is relentlessly rendered as the powerless victim.

Cannibalism in sapphic media, then, is a form of resistance. It’s a longstanding symbol of possession that sapphic relationships were never allowed to have. In Sheridan Le Fanu’s 1872 novella Carmilla, she writes of a young woman preyed on by a female vampire, the titular Carmilla. It was a pioneering work of vampire fiction, predating the more well-known Dracula by 25 years. It was also an early example of sapphic cannibalism—Carmilla punctures the human Laura’s breast and drinks her blood as an allegory for sexual acts.

It’s deeply unsettling, invasive, and taboo. But it brought a much-needed gravity to traditional portrayals of female romantic relations. No longer was it depicted as a frivolous activity of the bored elite, performed while giggling under floral sheets.

Rather, the introduction of violence and cannibalistic metaphors ascribes the dynamic of dominance and lust that was previously exclusive to heterosexual relationships. Goodbye, puppy love. Hello, possession, desire, and anger. We’ve been waiting for you.

But it also serves a role greater than just ascribing heterosexual dynamics to sapphic relationships. There’s something uniquely queer about this desire to adopt certain traits of your lover.

Toeing the line between jealousy and love seems to be a universal experience. I felt it growing up. Smiling at my best friend, watching her dazzle the room and effortlessly make new friends. In her radiance, she took all the light out of the room and left none for me. I felt nauseous, realizing that what should have been uncomplicated adoration was always tinged with resentment. But I couldn’t help it—as two pre-teen girls, we were constantly compared. My own parents constantly asked why I wasn’t as talkative as her. My teachers couldn’t write my report card without mentioning her name. We were a single noun in a sentence, ungrammatical and nonsensical without our other half. Wouldn’t it all be so much easier, I thought, if I just had what she had.

This constant competition forced between women—even those in a relationship—makes cannibalism a uniquely sapphic metaphor. It can never be simply about love and the desire to form a unified whole, as is depicted in heterosexual media like Bones and All. There’s an inherent element of jealousy. The line of reasoning asks: If I consume them, will I adopt their qualities, too?

It’s no surprise, then, that this niche metaphor has gained a foothold in queer female media. It addresses a decades-long cry to validate sapphic relationships as more than the superficial fooling around of young girls who haven’t yet found a proper male partner, coloring these pastel relationships with an air of darkness. Moreover, the very act of consumption—the crackle of cartilage grinding up against molars—also serves as a morbid, hyperbolized depiction of the jealousy inherent in many homoerotic female friendships. And that, importantly, is not love.