“Helen, you should call yéye more often.” My father says this one afternoon as he loads the dishwasher, in a tone so normal it’s as if it is an afterthought.

I look up from a book I have already read a thousand times. “Why? Is he okay?”

It is then that my father tells me about the diagnosis. About the mass growing in yéye’s lungs—already weak from decades of toil at high elevations. About the doctor in Chengdu, informing yéye and nǎinai—my father’s parents—that a biopsy and resection would not be possible without severe complications. About the phone calls home, tucked away in our basement in the early hours of the morning, concluding that nothing could be done.

“But don’t mention the cancer when you call. yéye and nǎinai can’t know that you know. The stress will be bad for their hearts.”

____

In Chinese culture, there is a deep-rooted tendency toward secrecy, particularly when it comes to bad news. Often, we withhold distressing information from our loved ones, believing that this will protect them from pain. What we fail to realize is that such secrecy can cause harm in ways we don’t fully understand. A study from 1999 explored this phenomenon through in-depth interviews with 15 Chinese families in Singapore, examining their adaptation to a child's chronic illness diagnosis. The study revealed that the disclosure of distressing information was selective, governed by the instinct to protect the family unit. Secrets, it seemed, were kept between parents and children, between spouses, between the family and the community—driven by a collectivist cultural inclination to maintain harmony.

There are layers to this secrecy. My father kept the news from me and my brother for weeks, making sure we only learned about it when absolutely necessary. And now, he expects us to keep it from yéye and nǎinai, as if adding another secret will somehow lighten the burden. Instead, it multiplies the weight. We’re all hiding from each other, pretending that everything is fine, when the truth is that we’re all hurting. What if yéye senses the unspoken tension between us? What if, in trying to protect him, we’re only isolating him further and cutting him off from the reality that might allow him to process what’s happening?

I wonder if—in this tangled web of secrets—we are inadvertently keeping ourselves from fully grieving, from fully connecting. The weight of this silence is suffocating and I can’t help but feel that it’s pushing us further apart when we need each other the most. In keeping the truth from yéye, I feel the weight of the silence between us as though there’s an invisible wall that prevents me from expressing the depth of my concern. What hurts most is knowing that I can’t offer him the comfort or support he deserves—not truly, not openly.

____

Later that evening, we are clustered around the kitchen table, the four of us: my father at the table’s head, me next to my little brother Evan, my mother across from us. The remnants of dinner have been cleared away to make room for my father’s ancient Dell laptop, on which plays a video titled “Evan_Helen_2009.mov.” It is not often that we all inhabit this house at the same time these days, rarely even together for mealtimes; it is approaching my fourth year away from home and the final summer before Evan embarks on the same exodus. I take a moment to appreciate this snapshot before me—one that will become increasingly rare as time passes.

In the video, I am learning to ride a bike without training wheels. It is a summer day not unlike this one, and my hair is pulled into pigtails, pink sneakers jammed down onto the pedals as I pedal furiously around the cul-de-sac of our old neighborhood. A toddler-sized Evan rides a plastic tractor likely bought from the Toys ‘R’ Us by the Somerville Circle—the store a relic that has been out of business for years now. My mother stands behind the camera, narrating the scene with a voice that’s both familiar and softened by the years, as if time itself has gently dusted off over a decade of memories.

yéye is there, dressed in his oversized button-down shirt, trailing close behind me. I recall yéye’s evening strolls, how he’d lumber down the sidewalk with his hands folded behind him. But in this video, instead of supporting his stooped back, they hover just above my little girl’s shoulders, poised to catch me at the slightest hint of a wobble as if anticipating any fall that might come my way. At one point in the video, Evan abandons his tractor to attack me with tiny fists of fury before running back to our mother. I retaliate, riding my bike straight into his tractor while simultaneously crying out in outrage. yéye gently scolds us both, though he looks more amused than stern. Our attention quickly shifts, and we move on.

Back in the present, we are in hysterics over the juvenile shenanigans of our childhood selves. Even Evan, having long outgrown his days of violence and transitioned into a regal stoicism, can’t help but chuckle at our antics. “yéye will love this,” I say, now sober, shaking off the remnant of the careless past. The image of my grandfather’s hands, always ready to catch me, persists. There is a reason why we are here watching old home videos, all together for once despite the flurry of our adult lives. We hope to send these videos to him and my nǎinai ahead of our trip back to China in December. The thought “in case December is too late” is unspoken but palpable among us. At least yéye can see us this way, we tell ourselves. It’s so very human, in the face of looming catastrophe and an uncertain future, to reach back toward the past for comfort.

________

I spend that summer working at Memorial Sloan Kettering, one of the most prestigious cancer hospitals in the world, conducting research on a disease I’ve been studying since freshman year of college. Cancer has always felt like a puzzle to solve, an opportunity to rewrite the stories of patients and families who endure the unimaginable. I’ve explored new ways to bridge the gap between research and care, uncovering hidden narratives within patient genomes to inform novel treatments.

I have a plan: four years of medical school in New York City, continuing my research at MSK, followed by another six years in residency and fellowship, all culminating in a specialization in pediatric oncology. Throughout college, I’ve followed this path with deep conviction in its purpose. I tell anyone who asks that I am confident, secure in my future helping families navigate the heartbreak of childhood cancer. But when cancer burrows its way into my own family, the distance between research and reality becomes painfully clear.

An ocean separates yéye and me, but it isn’t just the 7000 miles of physical distance between New Jersey and Chengdu—it’s a chasm of knowledge I hold that he doesn’t. I know about treatments, emerging therapies, and the possibilities that exist in the oncology community. But even with this foundation, I grasp at fragments of understanding; I am too inexperienced to make a real difference. At the end of the day, I am still just a college student, far from being able to help in any real way.

I think of Dr. Gormally, the thoracic oncology fellow I am collaborating with on a clinical trial to develop personalized T-cell therapies for lung cancer patients. During lab meetings, our work seems so cutting-edge and promising. But yéye and nǎinai, alone in another country, cannot even figure out how to make a copy of the DVD with yéye’s imaging results. They fight for five minutes of the oncologist’s time when they seek a second opinion. An unreasonable anger swells within me toward fate for placing this burden on us now instead of in 10 years, when I can do so much more. Maybe if I possessed a white coat and a stethoscope and the title of “Doctor,” yéye would see me as more than just his granddaughter—that little girl with pigtails and pink sneakers—and listen if I told him not to give up.

Just give us more time, I scream at the universe.

________

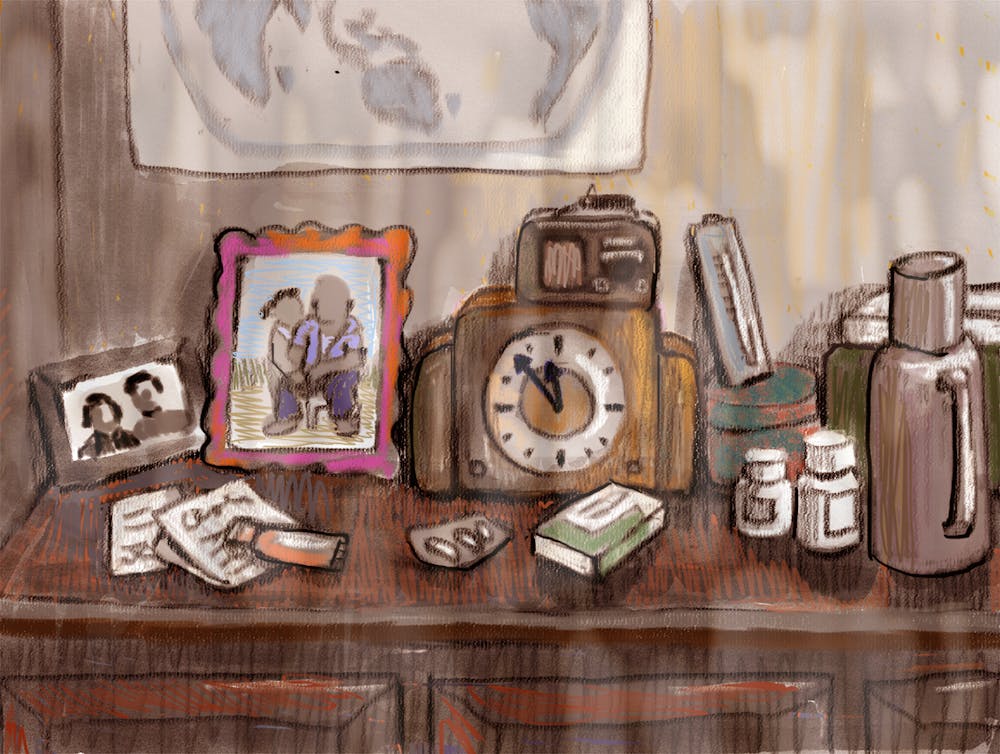

A week after we unearth “Evan_Helen_2009.mov,” I am staring at yéye again—this time through the dim glow of a WeChat call. I sit propped up against my headboard while my grandfather appears on the screen. As always, he holds the phone too close, so that the top half of his face is cut out. But I see that he is seated on a couch in his nursing home, and I notice the tubes running from his nostrils, supplying much-needed oxygen to his failing lungs.

yéye’s greeting brings a rush of familiarity, and yet I can’t stop thinking about the version of him in the home video—how he stood with his hands out, ready to catch me if I tipped over. He has always been there, whether it was walking miles in the summer heat to buy Evan an ice cream bar or waiting at the corner of our cul-de-sac every afternoon for the two of us to tumble out of the yellow bus, hands folded behind his back. But now, staring at him through the pixelated screen, I realize we are separated by more than just distance; we are also separated by time. I long to be the one holding out my hands to protect him, the way he has always done for me. Instead, I pretend I don’t see the oxygen tubes, ask yéye about his day, and say nothing about the cancer.

yéye and nǎinai can’t know that you know.