Holding my iPad against my body, I steadily lifted myself into the rolling chair. Once seated, I laid the tablet on my lap and peered out through the window. My grandma, a tiny Asian woman in a straw hat, was pouring water from a mug onto the garden plants in our front yard. After each watering, she stared at the plant, standing straight. Its blooming flower, its leaves, its branches, its soil. It was a curious sight to watch her as she looked on to her garden—teeming with plants that have lived since long before me. After a while, admiring her repetitive process, I picked up my iPad and turned it on.

—

Curling myself into a tight ball, I rubbed my hands back and forth against the nylon fabric, feeling around for a moment of heat. I was stuck inside a fully enclosed sleeping bag, within a large tent that trapped little heat, on a remote coast in northern California, in the middle of a summer night. The screeching wind beat at the thin layers of the tent walls, and I listened in on the warped breathing of my parents’ snores. I had not seen a shower in an entire day, and any fresh clothes I put on immediately became a biohazard. To minimize the number of trips to the Porta Potty, I even thought of peeing my bed…or here, the sleeping bag.

Even in the middle of the great outdoors, I locked myself up in the tent with a pre-downloaded TV show on my iPad. Only in desperate times, I planned, would I touch my device—every percentage of battery counted. By the end of the trip, though, I spent the majority of my trip watching TV and very little time outside my tent. When I lost interest in the German Netflix show about drug dealing, I resorted to playing cards with my brother, cousins, extended family—just about anybody. I counted down the hours until I would leave this makeshift dungeon of tents.

Above all, while I stuck to eating instant ramen throughout the entire, two-day camping trip, I refused to take a shit. Without a way to wash my hands? This “outdoors” experience at the age of 15 left me with a lifelong lesson: Don’t go outside.

—

“We should go on a hike!” my friend suggested.

We were deliberating on ways to make a Texas road trip fun. My friends were devotees to the sun: one played tennis on outdoor courts everyday, and the other loved to play with her dogs in a vast backyard. In our Texan hometown, built on a swamp, solar rays burned our skin with a tingling sensation. Any time I took a step outside, a rush of mucus ran through my nose, while the mosquitoes hastened to my arms and legs. The sharp heat spun my already-dizzy head so that I could not even stand.

“Absolutely not,” I mechanically responded. My refusal was not a matter of discomfort but survival. After numerous proposals and vetoes, we came to a compromise. We would do a lazy river as part of our road trip.

—

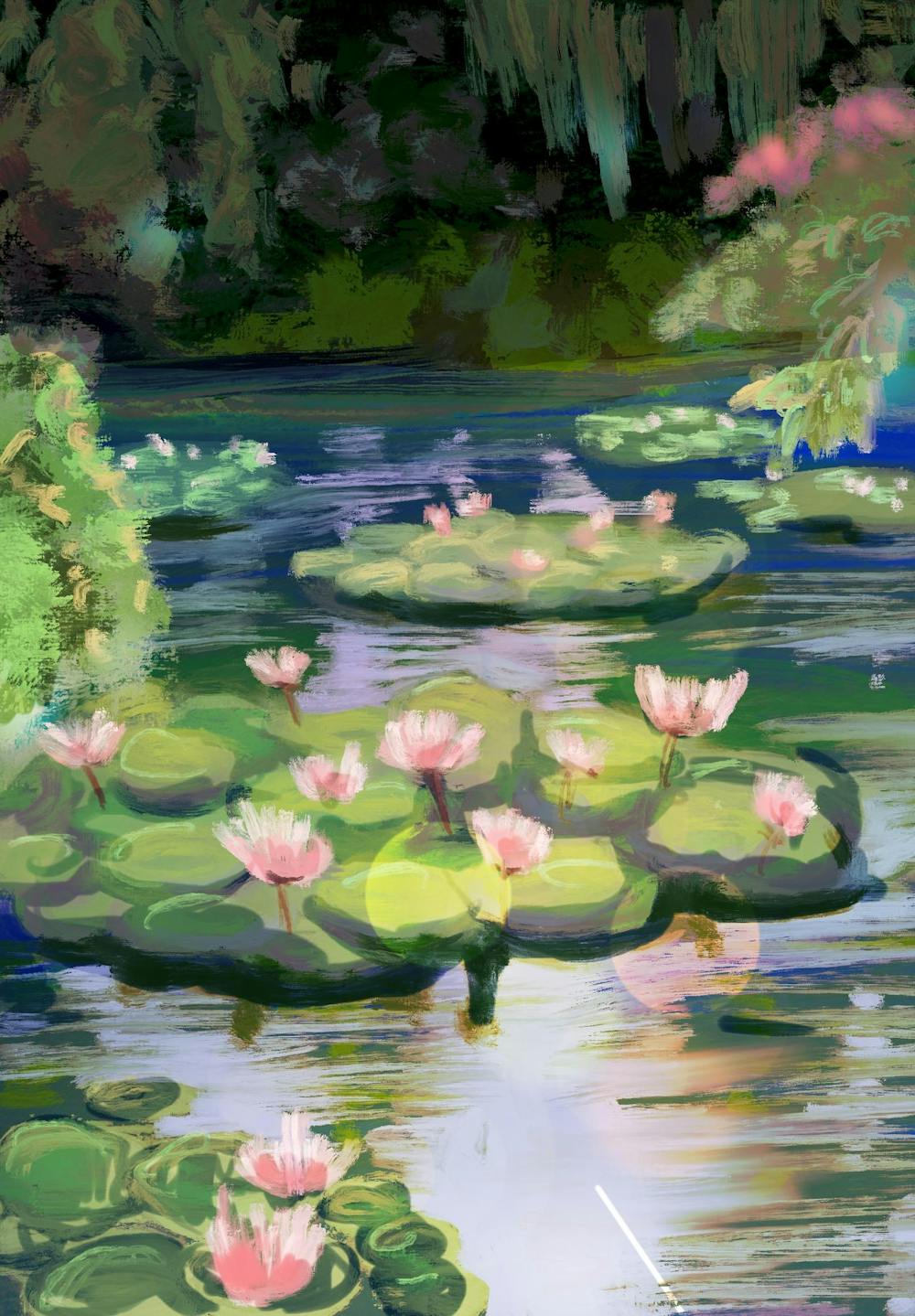

I focused my eyes in hopes of remembering everything I saw. On this light, sunny day, Monet’s garden brimmed with leaves of rich, vibrant green, married with the bright pink blossoms that rested closely together among the trees and grass. Scattered throughout were delicate flowers of soft blue, orange, and white that stood utterly still, drawing me into a moment where nothing else but this existed—and only for that mere moment. Families of lilies floated around in the pond alongside the surface’s gentle ripples, slowly drifting this way and that way, underneath a green bridge intertwined with fluffy bushes of even more green.

I strolled along the same pathways again and again, in awe of a near-perfect beauty. The pictures I took were not to capture the visual but to remind myself of a feeling—of privilege. My family will likely never be able to witness what I have witnessed. Visiting this garden was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for me but an impossibility for my parents. All of those who came before me were not thinking about seeing the beauties of nature but instead focusing on working to better the lives of those in the future. Where I was, accessing the most beautiful of places, was a culmination of their generational labor.

—

On the train, my legs and feet went numb from my sopping wet shorts and socks, coupled with the air conditioning. Passerbys glanced at my bloody face, covered with scratches and bruises and bandaging. My heavy eyelids shut my dry eyes, which had been open from 5 a.m. to 8 p.m. Although I physically suffered, I would have done it all over again—biking around a lake in the Alps and swimming in the glowing blue water, despite the thunderstorm all day. Falling off my bike there only made me grateful that I could fall off there of all places. Perhaps I felt that the physical pain was worth beholding such a sight of nature.

—

“Let’s go hiking.”

My friend, who once played tennis on outdoor courts everyday in high school, wanted to show me what her college city offered. There was even a fun little troll sculpture I could see in the park we would go to. Checking the weather app, I saw that the summer heat in Texas was around 100°F.

“Sure, why not?” I was obligated—by my nature, by where I come from—to see.

—

At Trader Joe’s, I peruse the assortment of flowers for the sake of looking at the charming selection. While I ultimately pick up a bunch of dried lavender—a no-commitment plant—a pink-fuchsia orchid catches my eye. An inexplicable desire makes me lift its pot and gently place it into the shopping cart—an immediate, pulling love. I think it would look great in my dorm, except that I have never taken care of a plant before and, in actuality, have always been against it. I simply remind myself that, according to Joan Didion, orchids require acute attention, and yet its beauty is rewarding in itself.

After setting the orchid in an ideal place on a shelf, I let myself fall into a seat admiring it. Its blooming flower, its leaves, its branches, its soil. As I water the orchid, I am reminded of growth, sure and steady. Of how I am trying to continue the family tradition of gardening, of how I am the product of a want to continue, of how I will continue so that others can too.