On April 22, at the peak of last year’s campus activism, an Instagram account posted a photo of a poster which read “Rape is resistance.” The post claimed that such posters had been distributed by pro-Palestinian protestors at Columbia, and without any meaningful fact-checking, the post quickly went viral and accusations against the Columbia protesters spiraled out of control. It was later proven that the poster had never been present at Columbia and that photos of the same poster had been circulating for at least a month prior.

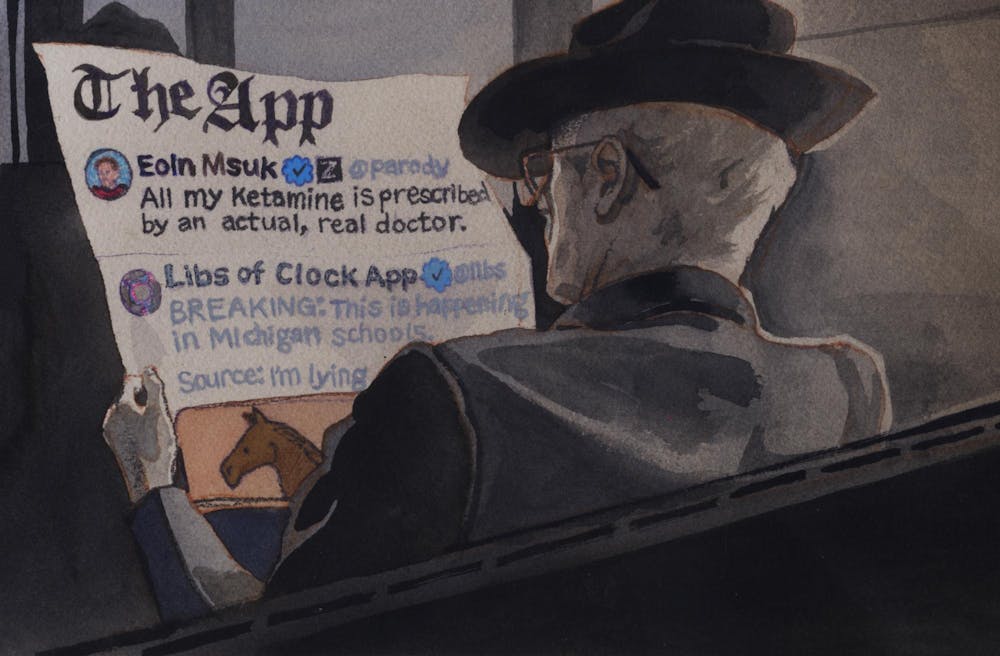

This pattern of events is hardly rare. Six days later, after protesters raised the Palestinian flag over Harvard Yard, photos posted without context rapidly led to claims that the Harvard administration itself was responsible. These events show the dangers of trusting social media as a news source.

While it has always been difficult to convince people to engage with ideas they disagree with, the lack of meaningful discourse in the digital world has resulted in years of escalating hostility. Content on the Israel-Hamas conflict has been especially polarizing, with influencers on all sides often omitting certain facts to make their argument more convincing. The battle playing out on millions of TikTok and Instagram accounts has been allowed to play far too big a role in the actual debate on the subject. Amidst the heated passions and partisan debates, social media allows us to lose track of the facts far too quickly.

A key component of what makes social media so addictive is the platforms’ ability to learn what content viewers enjoy and recommend more videos or posts like those. This seemingly harmless feature is also what makes using social media as a news source so dangerous. The same algorithms that allow users to spend hours watching their favorite content also inherently favors promoting and encouraging the user’s existing biases, resulting in many never interacting with content they oppose and even the formation of extreme beliefs.

No news source, even the most established ones, are free from bias. But the principal difference between a TikTok account and an established media source is that the latter usually has some degree of fact-checking in place to avoid publishing falsehoods. Even so, fact-checking is difficult and even the most robust newsrooms have at times failed to combat widespread misinformation. If even professionals sometimes get it wrong, it’s reasonable to assume most users on social media are unequipped to accurately fact-check.

Social media itself is not inherently biased or harmful. Nearly every major news organization has a presence on Instagram, and I sometimes find myself scrolling through their feeds to catch up on events. What’s important is to ensure the trustworthiness of the source itself and practice informed consumption — not just believing the first TikTok post on your feed.

Lucas Guan ’27 can be reached at lucas_guan@brown.edu. Please send responses to this column to letters@browndailyherald.com and other opinions to opinions@browndailyherald.com.