TW: eating disorder

1.

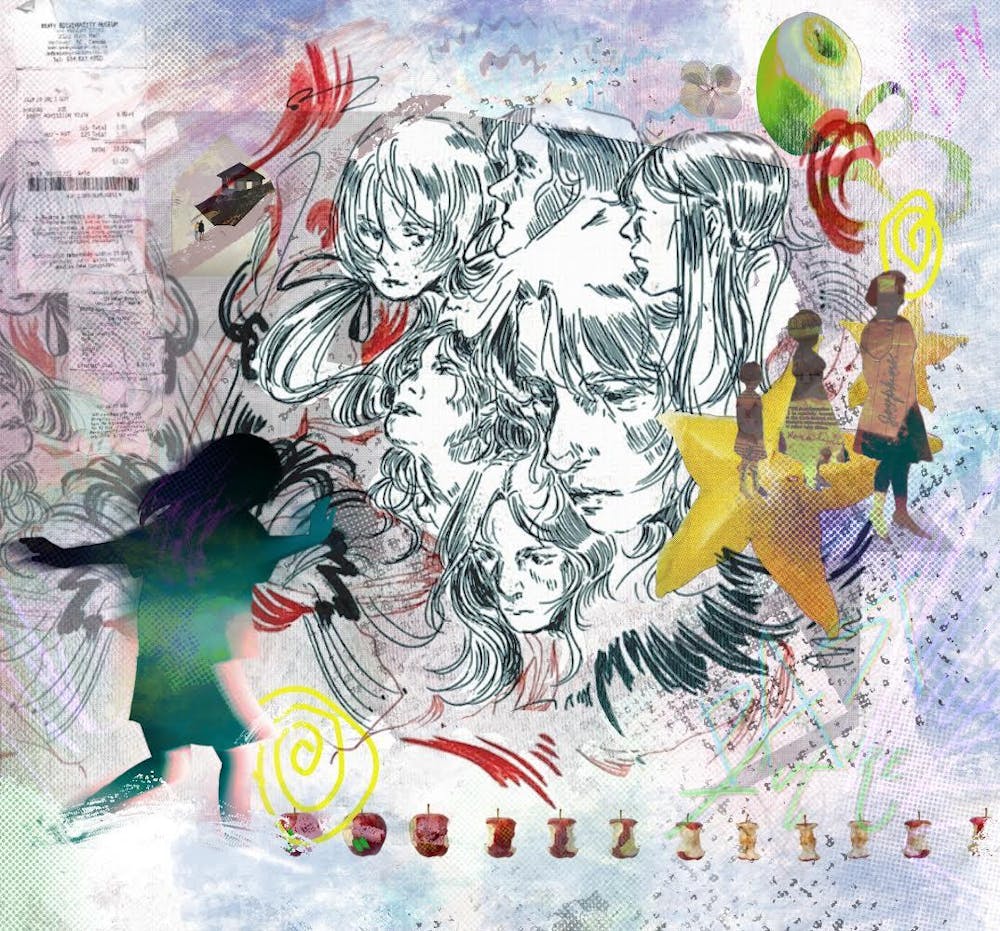

Not yet tall enough to reach the kitchen counter, you are your grandmother's shadow as she prepares dinner every evening. You spend your days in your grandparents’ kitchen instead of at daycare, like the other children on your suburban street. As Grandmother kneads dough for dumplings and Grandfather hauls in pillow-sized bags of jasmine rice from the Asian supermarket, you recite rhyming Chinese lullabies and twirl in circles on the sticky vinyl floors. You mimic Grandmother's posture, as proud and straight as the oldest tree in the forest, standing on tiptoes to watch her weathered, wrinkled hands measure smooth grains of rice from a bulging sack. The grains make a “shhhhh” sound as they tumble into a metal basin. In a ritual you observe with awe, Grandmother rinses and rinses the rice with cold water until it turns the basin cloudy.

2.

Amid the din of the Hamilton Elementary School cafeteria, you crane your head from your spot at the end of the long table in an attempt to join the buzzy conversation of the popular girls. Your grandmother, in an attempt to help you fit in, now kneads dough for pizza. But the pizza is too thick, too bready, with hot dog slices instead of pepperoni. At lunch the next day, you stare enviously at the Domino’s served to your friends on cardboard trays with cartons of chocolate milk. How can you ever hope to fit in, if even your pizza stands out among the others?

3.

In the basement of Rutgers Chinese Community Christian Church, you sit on a metal folding chair next to children who are familiar and yet not your friends. You squirm, restless, and feel the backs of your thighs unstick from the cold metal. “How great is our God…” the other children intone, mouthing along to the lyrics projected on uneven white walls. But your lips are unmoving, shoulders hunched and head bent—to anyone else, it seems you are praying. In the dim light, no one sees that your eyes are squinted and your fingers are poking and prodding at the skin on your thighs. Like Grandmother kneading dough, you think. You are in fourth grade, your body already a dwelling you wish to escape.

4.

You are not allowed to eat apples with the skin intact—all those pesticides. If you want an apple as an after-school snack, you have to wait patiently by the kitchen counter and watch Father or Mother or Grandmother take the largest and shiniest apple from the bowl, scrub it furiously under a stream of water, and begin to peel. You roll your eyes as your father recites (for what seems like the thousandth time) a warning about pesticides, chemicals, and GMOs, but deep down, you know that this is how he shows his love.

Here’s how your family peels apples. Grab a knife, probably the small serrated knife sold to your family by one of those door-to-door saleswomen as part of a set. Holding the apple firmly in one hand, press the sharp edge of the knife against the skin at the top of the apple, like a surgeon making a sideways incision. Slowly turn the apple as the skin comes off like a ribbon. Once this ritual is done—the apple stripped bare, a ribbon of peel dumped unceremoniously in the metal tin your family keeps next to the sink for food scraps—cut the apple into bite-sized pieces. While your mother and grandmother know how to slice the apple so that each cube of light yellow flesh is nearly identical to the next, you know your father’s work by the mismatched, ragtag assortment of apple chunks.

5.

Polo shirts untucked from navy skirts, 10 girls crowd around a table meant for five. In front of you is a bowl of chicken noodle soup and an Italian sub wrapped snugly in clear plastic—served to you by the kind lunch lady with wrinkles around her eyes. What is in an Italian sub, you do not know—only that it is something American girls eat. You miss your mother’s home-cooked meals, itch to peek at the worn paperback hidden under the table—but those are comforts of childhood that must be left behind. In this private-school lunchroom, you can blend in. And isn’t that all a middle school girl hopes for? The days of smelly thermoses and old lunch boxes are no longer. If you wear the same clothes and eat the same food as these rich, private-school American girls, you too can be an American girl.

6.

In the basement you scrounge up a dirty mirror, propping it up in your bedroom. While doing homework, your legs move of their own accord, delivering you to your reflection, who looks you up and down. The mirror becomes your constant companion, a hypnotist luring you in. It invites you to scrutinize your complexion, your nose, your stomach, your legs, until you have collected a list of things you wish you could change.

7.

Your middle school doesn’t have a track, so your coach—also your seventh-grade science teacher—sprays uneven white lines to form a small 200-meter track on an unused grassy field. You choose track as your spring sport because Ryan, the most popular girl in your grade, is a track star and you want to be friends with her. Every day after school, you are a hamster running around in circles on that makeshift track—arms pumping, sneakers squishing into the overgrown grass, sweat soaking the gray Far Hills Country Day School t-shirt. You begin doing ab workouts on a purple yoga mat your mother buys you from Walmart, obediently copying the movements of models on YouTube who promise you six-packs like theirs. In the locker room before track practice one day, you are changing into your sports bra (you don’t need one), when you overhear Ryan and the other girls debating over who the skinniest girl in the 7th grade is. When Ryan mentions your name, you turn away, hiding your smile in the cotton of your smelly gym shirt.

8.

High school is a season that shepherds in change. You begin to eat apples with the skin intact—forgoing the tradition of watching a loved one peel away skin and carefully slice it into pieces. Other changes: orange patches caked over red pimples, courtesy of a tube of heavy-duty concealer from Sephora; fewer Skype calls with your grandparents, who can no longer make the 13-hour flight to the US; googling restaurant menus beforehand to ascertain the healthiest option. You scoop out smaller and smaller portions of sticky jasmine rice at dinner every night, and watch your reflection in the mirror shrink too, until rice becomes as foreign a food to you as your American classmates. At night, your stomach growls at you, angry at this lessening, but you ignore it.

9.

Your senior year of high school is consumed by discipline. Every morning, you lace up your running shoes before the sun rises, hitting the pavement for a few miles. The thud of your feet on the concrete is a rhythm you depend on. The early morning fog and the biting cold feel like penance for the body you’re determined to change. You’ve cut out carbs entirely, trading family meals of rice and noodle soup for fruits and vegetables that never seem to fill your stomach. The vibrant flavors of your grandmother’s cooking are now distant memories, replaced by bland, calculated meals. But it’s working—you’re getting thinner, and you’re getting faster. Each run feels like victory, and each rib you count in the mirror fuels your drive. It's no longer about health or fitness; it’s about control. You’re not just training for cross-country races anymore—you’re in a battle with your own body, one that you can’t afford to lose.

10.

It’s the summer after your sophomore year of college when your period vanishes completely, and instead of panic, you feel a strange sense of relief. To you, it’s a sign that you’ve finally gotten it right—that all the carb-cutting, the endless miles, and the calorie restriction have brought you to the perfect balance. No period means you’re lean enough, disciplined enough. You never seek a doctor’s help, brushing off the warnings you’ve read about RED-S. You convince yourself that this is just a natural consequence of being in control. How could you, of all people—so disciplined, so regimented—damage your own body? But in the back of your mind, there's a quiet voice—one you refuse to listen to—hinting that this might be too much. The fatigue, the constant injuries, the brittle nails—they’re all pointing to the same truth: You’ve pushed your body too far, and now it’s pushing back.

11.

The breaking point comes during what’s supposed to be a routine run. You’ve mapped this route so many times you could do it blindfolded, but today, something feels off. Your legs feel like lead, your breath comes in shallow gasps, and halfway through, you’re forced to slow to a walk—a betrayal of everything you’ve trained for. You bend over, hands on your knees, fighting the dizziness, but it’s more than just physical exhaustion. As you stand there, sweat dripping down your face, it hits you: The person you’ve been chasing all this time is a stranger. You’ve spent years defining yourself by how you look, how fast you are, how “clean” you can eat. In that pursuit, you’ve lost not only your period, but pieces of your identity—your connection to family, your culture, the traditions that once filled you with warmth. You barely remember the taste of your grandmother’s dumplings or the joy of twirling in her kitchen as a child. You’ve been running toward a version of yourself that you no longer recognize, and suddenly, all the discipline and control feel hollow. Standing alone on the side of the road, you realize the real loss isn’t just your strength—it’s the person you used to be.

12.

Recovery isn’t linear. College becomes a complicated dance between old habits and new growth. You begin to reintroduce the foods you once feared, starting with small portions of rice and yaki imo sweet potato at family dinners, then dumplings, and finally the rich, flavorful dishes that had been absent from your life for so long. You rediscover the joy in cooking with your family, learning the recipes that your grandmother has passed down through generations. In the process, you reconnect with the parts of your culture you had distanced yourself from. Through storytelling, food, and community events, you rediscover the parts of yourself you had suppressed, realizing that your identity is not something to hide or reshape—it’s something to embrace. Your body, once a battleground, starts to feel like home again.