At the sand-colored strip mall near my elementary school, wedged between the dry cleaners and ice cream parlor, was my sister and I’s childhood playground. On long summer days or rainy afternoons, my mother would park beneath the dusty sycamores and walk us across the asphalt to the glass storefront. After wandering the aisles and craning our necks to size up the images in front of us, we would pick out our week’s treasure and take it home—a promise for the evenings ahead. The Silver Screen Video store was paradise, but one day we lost it—another casualty of the rise of streaming services in the 2010s. Until recently, I never noticed the store’s absence; digital movie rentals must have had me in a chokehold by the time it shut down. So all I know is that sometime in my adolescence it disappeared, leaving nothing but visions of sunny days and plastic-filled shelves in its wake.

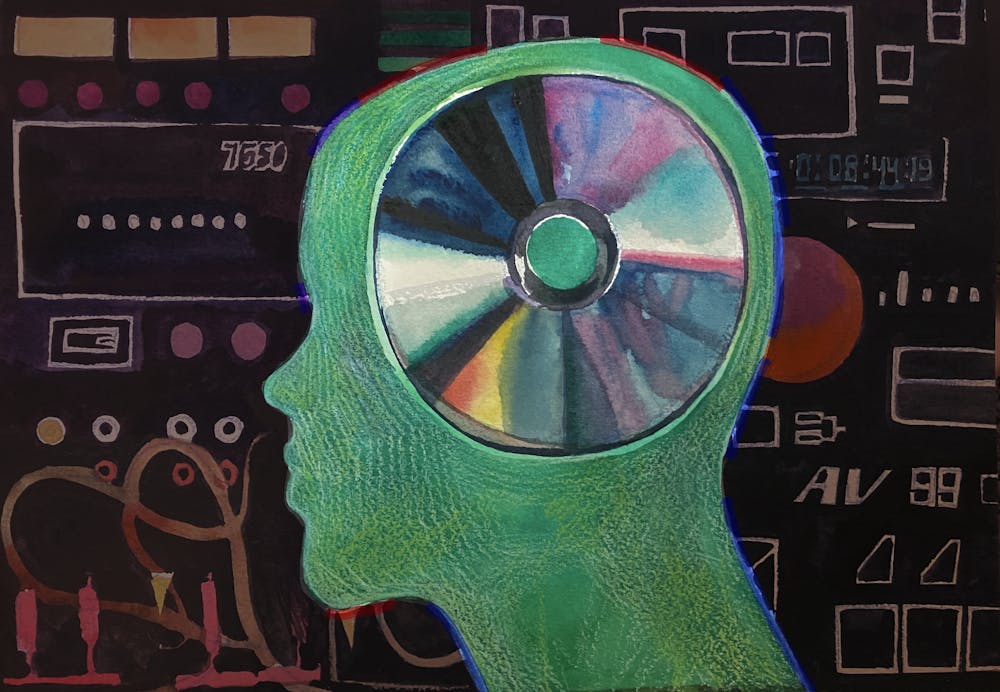

I, like many other Gen Z-ers, was born in the early 2000s, a few years after the dotcom bubble burst. My childhood is an amalgamation of past and future—CDs and music downloads, DVDs and cable. I remember watching Annie on the iPad with its cracked blue case just as much as I do curling up in my parents’ bed as my mom popped Beauty and the Beast into the VHS player.

Thus, it irks me when people describe Gen Z as a post-physical media generation. While my memories are hazy, I’ve talked to others my age who have similar anecdotes to share: recollections of The Wiggles tapes or watching those old grainy Barbie movies on repeat. Yet, articles listing “10 Things Gen Z Will Never Know About” or videos that claim “Gen Z Has Never Seen a VHS Tape” believe our generation has never used a CD player or opened up a phonebook. When I see and hear these assumptions and stereotypes, I quickly become annoyed. You don’t know our childhoods, I want to scream.

While these assumptions anger me, I try to give my predecessors some grace. How often do I do the same thing? My brother is almost 12 years younger than me, a Gen Alpha through and through. He’s grown up with iPads and streaming services as his norm, with no understanding of this crazy thing called a commercial break. Sometimes I want to feel superior with my old technological knowledge. I have the urge to start wagging my finger and telling him how back in my day… but what’s the point?

I wonder why I feel this sense of twisted competitiveness about the technologies of the past. Perhaps a superiority complex is one factor, but I think more than that is a sense of grief for this long-lost past. I desperately want to defend these memories of my childhood, try to preserve them from the wear and tear of time. But it’s no use. What’s gone is gone. So instead I romanticize what I lost, become protective of these vanished technologies out of a nostalgic longing for some unreachable, idyllic past. For a simpler time.

⏮⏮⏮

I was going through my parents’ house this summer, helping them donate and sell things before they move next year. Knowing both my mom and I were sentimental, my dad kept reiterating that we no longer owned a DVD or CD player, so any tapes we kept would just collect dust. Nevertheless, as I worked through the DVDs, I struggled to let go. Shrek 2 was a staple of long car rides while the scratched collection of Dora the Explorer movies has left hazy, permanent visions of colorful parties and magical adventures somewhere in my subconscious.

As I attacked the massive CD collection, similar feelings arose: I remembered popping Christmas albums and ABBA’s Greatest Hits into the player in the living room, the hum of the machine under my palms as it prepared the disc to play on those cold winter nights. Running my finger over each case, checking the copyright dates and price tags, I found worlds in my memories from the decades before I was born—stories and speakers I had never encountered. Where had my parents bought these albums? Who had they listened to them with? What was happening in their lives, in the world, as the discs spun round and round? It was a strange desire that dug deep into my chest, this longing for a universe I would never know. I eventually shoved all of my favorites into a box, ignoring my dad’s objections (when will you ever use them again?!) and sold the rest at a secondhand bookstore. As I turned from the tower of CDs on the counter and left the store, I tried to ignore the small pang of grief, the feeling that I had just given away decades of memories.

⏮⏮⏮

I’m not the only person gripped by this sense of nostalgia for pasts I have and have not experienced. Vinyl records and film cameras have become repopularized over the past decade. The cyclical nature of fashion has brought trends such as Y2K back into vogue. We live in an age of nostalgia, an era of longing for when things were “simpler,” both in and out of our lifetimes. How many hours have I lost scrolling through my old photos, wishing things were “how they used to be?” How many pieces have I written reminiscing about my childhood home and that unique magic of the single-digit years? I know it’s futile. As intensely as we crave what once was, as much as we pine for those bygone days, they will always remain unreachable. Still, there is something about the past that draws us. Victoria Owen writes, “The average Gen Z childhood has been defined by events that rocked the world. Terms like ‘Pre-9/11’, ‘Pre-financial crash’ and—more recently—‘Pre-pandemic’ have been slotted into their lexicon since birth. As they’ve grown up, they’ve been unconsciously steered to look back at how the world was before these major disasters—even if they don’t have any concrete memories of what that world looked like.”

The astonishing amount of change in the world throughout our lifetimes has led to a longing for a past that we barely had. I spent my senior year of high school trapped inside during a pandemic, wishing to return to a time when things were “normal.” I’ve come of age in a period of economic, political, and global uncertainty, a time marked by intense declines in mental health. I’ve grown up surrounded by the unspoken pressures of, and constant communication through texting, social media, and the internet. I’m not alone in feeling the weight of the internet age; according to a survey by the New York Times, 34% of Gen Z wishes Instagram had never been invented and 45% would not give their children a smartphone before high school. These technologies are practically staples of our generation, yet there seems to be a collective desire for escape. I’m grateful for how the internet and smart devices have improved life, but I’ve always secretly imagined what it must be like to live in a world where I didn’t have to overthink every text I sent, every image I posted. A simpler world.

Still, as much as I want to run back into some mythical past, I know it’s impossible. Silver Screen Video is gone. The CD player broke long ago. No amount of nostalgia can transport me back. But perhaps that’s not such a bad thing. The present is a place of so much beauty and goodness. I’m attending my dream school. I’m surrounded by friends and family I love. And the world, despite its messiness and pain, is still full of hope. Medical advancements are bringing about unimaginable cures for previously deadly conditions. We can connect with others across the globe in ways that were impossible even 20 years ago. Time moves fast, but I will continue to change and adapt, just as technology has. Maybe one day Netflix will be archaic, my phone a relic my children have no clue what to do with. And if the thought of that seems scary, I know that I can still curl up, find one of those old movies, and sink into them again.