All those weeks ago, in the middle of Super Bowl LVIII, Beyoncé came along and “broke the internet” with the surprise release of twin country singles “TEXAS HOLD ‘EM” and “16 CARRIAGES,” a preview of her upcoming album. Almost immediately, a fiery debate ensued among the self-appointed protectors of the country genre: Could Beyoncé really qualify?

“TEXAS HOLD ‘EM” has all the telltale trappings of a country song: the hollering inflection, the call and response, the pining strings (specifically banjo), the gravity of a pun at its center, and if you’re looking for the signs, she’s got the “liquor,” the leather, and the “Lexus” to back it up. This wasn’t the first time she’d explored country, though: In 2016, Beyoncé sang “Daddy Lessons” with the Chicks (née Dixie Chicks) at the Country Music Awards, a bold performance with a rich Texas twang.

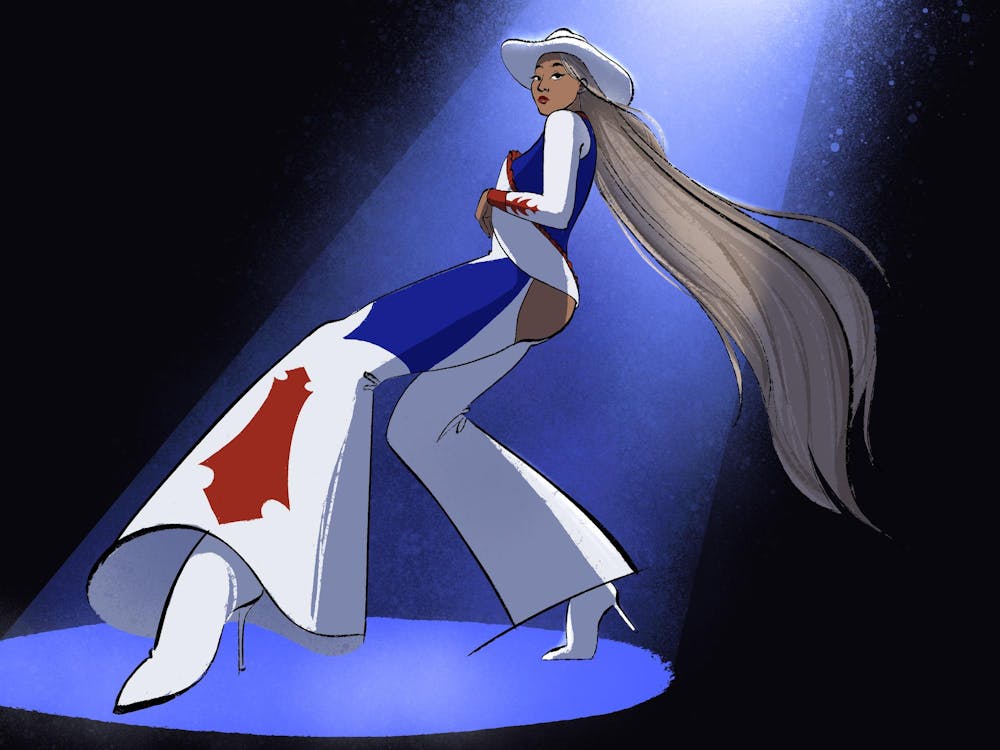

Beyond genre, “Daddy Lessons” and “TEXAS HOLD ‘EM” also told us something deeper about Beyoncé’s oeuvre: she comes from a Louisiana Creole mother and Texan father; her songs are often reflections of that heritage. Just listen to the saxophone solo at the CMAs: soulful, smooth, muddy as the Bayou, and performed in a pair of knee-high cowboy boots. Much of her music is like a good old-fashioned Texas cookout: She pulls contributions from each relative onto her plate, and tops it off with the “hot sauce in her bag” for a signature Beyoncé Knowles-Carter kick. Each album has been an artful index of the Beyoncé story (see Beyoncé) and, taken together, her catalog might be heard as a kind of American story: a tale of cultural exchange with music as its melting pot.

That is, until COWBOY CARTER dropped: now, it’s an “AMERIICAN REQUIEM”.

The newly released album isn’t entirely country but instead a study of genre and the American musical canon, featuring everything from a Beatles cover to a “Good Vibrations” quote to a Willie Nelson voice-over. In a project that sounds more like my History of Popular Music course syllabus than a contemporary album, country becomes a mere bullet point. It’s less musical and more musicologist, adopting a deeply academic approach to songcraft that privileges direct citation over interpolation. The cookout becomes a library.

On COWBOY CARTER, Beyoncé seems to have left her passion for composition at the door—gone are the calls for complex and cohesive musical “formation.” Instead, we’re left with a post-modern treatise of disjointed historical detritus where discography dissolves into cultural document. The problem isn’t purely that she’s citational, for she’s long been working in that mode. But Beyoncé at her best treats citations as less source and more material: They’re raw items, malleable in her grasp. This time, she’s ceding space to the sources themselves—not just the text, but the people—and if Beyoncé is best appreciated as auteur, it’s disappointing to watch her drop the pen.

The album begins with “AMERIICAN REQUIEM,” a moaning and mournful ballad about death, destruction, and memory. Like a true requiem, the opening track establishes the album as a token of remembrance: she declares early on that “them big ideas are buried here” with piercing certainty. And yet, buried seems to carry two meanings: It’s buried as in disposed of, yes, but buried also means that they’re embedded into these songs. Those old ideas about genre are always there on this album, lying just six feet under each track. It’s an ominous opening introducing a duality that continually haunts this album: Are we remembering these ideas to say goodbye, or to preserve their memory? It seems we’ve been condemned to both.

“AMERIICAN REQUIEM” also explicitly positions the country industry as a primary provocateur of this project: “the rejection came, said I wasn’t country’nough.” It’s a small moment, but one that nonetheless presents discourse as the central concern of this album: As she tells us again and again, “there’s a lot of talking going on.” Shade aside, we soon learn that this is a discourse she’s determined to enter, as she repeatedly asks “do you hear me?” until finally, in the heat of exasperation, she concludes, “for things to stay the same they have to change again.” Here, she leaves us with a profound insight about musical innovation, but it’s also an insight that exposes the album’s fatal flaw: As she goes on to recall all these old American art forms, nothing really changes.

Indeed, the very next track is “BLACKBIIRD,” a cover that directly reproduces the Beatles' work—no samples, no remixes, no changes. It’s a simple resurrection. On Lemonade, Beyoncé cited the original “Blackbird” organically by folding a single image (broken wings) into her own symbolic repertoire; here, all is lost in following the author rather than the text. She’s assembled a veritable Avengers of young female country stars—young black female country stars—as background vocalists, but their only superpower is the ability to revive a group of tired old Brits. Tanner Adell, especially, seems like a natural counterpart to Beyoncé with her winking creativity and hip-hop inflected flare—nonetheless, “BLACKBIIRD” drains her of all that life force, whittling Adell down to nothing more than a symbol.

Perhaps nowhere is Beyoncé’s preoccupation with past voices more vivid than in the series of vocal interludes delivered by country’s legends. First, there’s “SMOKE HOUR ★ WILLIE NELSON,” featuring, you guessed it. The beginning of this interlude is stunning—it opens with the crackling of a radio as the dial oscillates between stations, bringing us a taste of genres, styles, and cultures that were once worlds apart, collated by a single change in channel. In less than a minute, Beyoncé has rendered all of American music readily available through the radio in a piece that’s subtle, performance-based, and evocative—in short, it’s art.

But all that art comes to a screeching halt when the radio reaches KNTRY: The Willie Nelson Channel. In walks Willie Nelson, the MC of the station, announcing Beyoncé’s next track. On KNTRY, Willie literally has his finger on the switch: he becomes both annunciator and arbiter of what counts as country. Sure, she gets a spot this time, but if genre is truly democratic, why have an electoral college?

And then there’s the next interlude: “DOLLY P.” Dolly might be an especially interesting interlocutor for Beyoncé—if only she were that. Instead, Dolly, like Willie, speaks only as the guard granting her passage: “Same hussy different hair color,” Dolly tells us, officially sanctioning Beyoncé’s “JOLENE.” Once again, we have a track that seems to believe Dolly is a necessary authenticator—a track that leans more on her acceptance than its own artistic merit.

Willie and Dolly are rivaled only by “THE LINDA MARTELL SHOW,” where Martell declares (two-thirds of the way into the album, no less) that “This particular tune stretches across a range of genres / And that's what makes it a unique listening experience / Yes, indeed.” The whole thing reeks of pedagogy.

For all its earlier attempts at aural archaeology, the album’s two forward-looking collaborations are some of its finest. “II MOST WANTED,” a collaboration with Miley Cyrus, almost makes Willie and Dolly’s impositions worthwhile; it’s an intricately woven duet that knots the outlaw thread into an elegant bow: We’ve followed the historical outlaws all the way up to our present ones, Miley and Beyoncé. Even sonically, the song’s hushed harmony and seamless call and response smoothly enact this artful integration of storylines.

****

There’s a photo, from 2008, posted on the cover of Texas Monthly. Beyoncé’s standing front and center in dark jeans and a form-fitting shirt with Willie Nelson on her chest. She’s got the same braids and bandana as him—except, while his arms are crossed, hers are placed elegantly on her hips. She’s wearing Willie as her attire, but the pose is hers; he’s just an accessory.

All these years later, Beyoncé adopts a similar posture on “LEVII’S JEANS,” a collaboration with Post Malone—just as she once stepped into the Willie shirt and dark blue jeans, here she picks up another country-coded item and wears it as a coating for a uniquely Beyoncé conceit: “I’ll let you be my Levi’s jeans / so you can hug that ass all day long.” Unlike all those disembodied voiceovers, here we have a song whose structure and style relies on her presence inside of it.

And then, there’s the guest verse from Post Malone. Malone is a challenging artist precisely because he is so plastic—the substance itself isn’t all that artful, but it’s structurally sound, and its plasticity allows it to adapt to any sonic environment. He’s the soggy white bread of popular music: Beneath a heaping stack of barbecue, he’s an inoffensive conduit, clinging to the juices around him; on his own, he’s barely appetizing, and certainly not flavorful. But as it turns out, his flimsy sound is exactly what this song needs: he can fade into the Beyoncé project, rather than the other way around. Like those jeans, he brings out the best contours of what she’s already been doing: “You’re my Renaissance,” he sings, and just like that, she’s back in the conductor’s chair.

With Beyoncé back at the helm, “LEVII’S JEANS” becomes an exceptional exploration of negative space—its drawn-out, drawling syllables serve as an opening ripe for her authorial arrival. Much like Malone himself, the song is understated yet ambitious: Everything you need to know about its aesthetics can be traced back to the line “giving high fashion in a simple white tee.” It’s minimalism as luxury.

Much of the rest of the album slips into a scattered stretch of songs perhaps best represented by “TYRANT”—a Dolly x DA Got That Dope collab that layers a scratching fiddle over anxious 808s, gesturing toward the kind of bass-powered country-rap that artists like Adell have mastered. But when the project finally comes to a close, it leaves us with “AMEN,” a soft variation on “AMERIICAN REQUIEM” which reiterates that this was always a memorial—only now, we know that it’s the material that’s dead. In meditating on musicians past, Beyoncé has somehow lost the thread of music’s present.

By the final notes, it’s clear that COWBOY CARTER took postmodernism beyond its limits: How can an album that stretches in so many different directions—from crooners past to trap beats present—possibly stay together as a cohesive piece of work? Aurally, it can’t, but since our experience is never enough with these songs, she has to tell us once and for all: “Yes, it crumbled.”

But all that musical crumbling ultimately seems like a contradiction on its own terms—in the very same song, she implores, “Can we stand for something?” reminding us that this sprawling experiment was never about music that does something, but music that represents something: All along she’s used her iconic guests as pillars, hoisting the message onto their backs.