Dearest Mathematics,

So much has changed since I last wrote to you. While 18 years with you had convinced me that my feelings toward you could never change, the last three years have proven otherwise. I am so proud of where we are today and all that we have overcome. Our brief breakup during the summer of 2021, when I left you in order to “find myself,” was the hardest yet most rewarding thing I have ever done. In all honesty, Math, I needed to hate you for a summer in order to love you for the rest of my life.

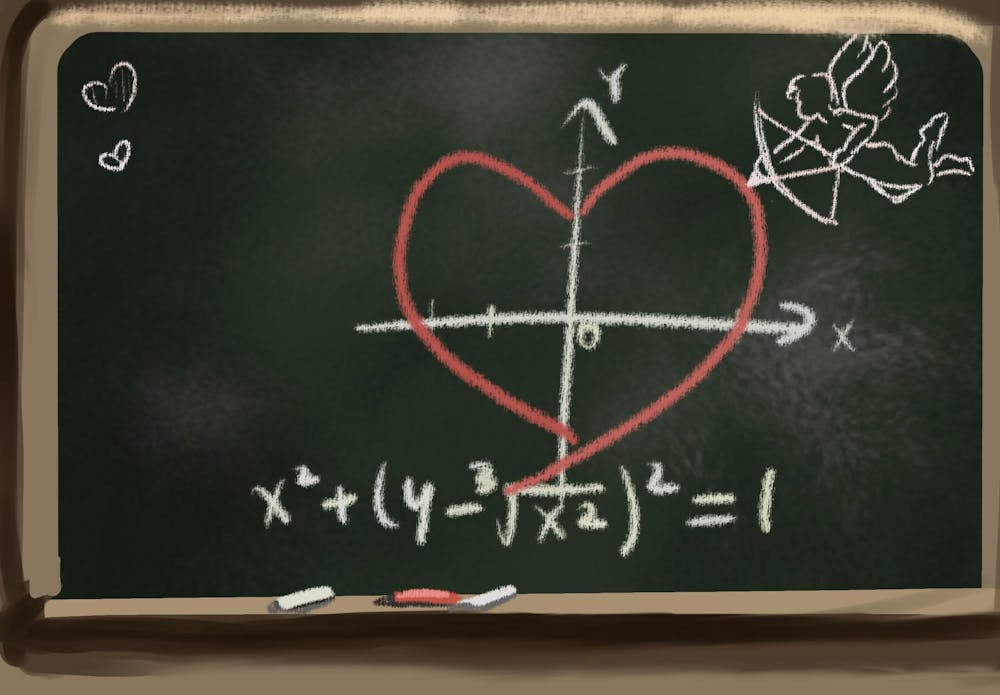

I shared our love story with the public on Valentine’s Day of 2021. Just a few months later, we faced incredible hardship in private. I went from loving you wholeheartedly to thinking I would never love you again. While attempting to learn multivariable calculus in my 100-degree dorm room in the middle of a Covid-19 summer semester, I was physically, mentally, and emotionally fatigued. Trying to understand you while I was too overheated to function, I broke down. At the time, I thought that I had reached my limit in mathematical understanding—that this was the end for us. I could not distinguish between my ability to function as a human being and my ability to do math. In the past, no matter how chaotic, tumultuous, and dysfunctional my life may have been, math was my constant. I could always do math, even if I doubted every other ability I had. As I once put it:

This [math] problem-solving process was one of the most beautiful things I’d ever encountered: The numbers, regardless of how arbitrary they were, gave me a sense of order that was integral to unraveling my world of disarray. I found magic and harmony and balance in you, a welcome juxtaposition to my disorderly state. It reminded me of the true goal of math: To reveal the greatest, most universal truths of life through depictions of our worldly experiences.

This time was different, though. Because if I could not do math in the social, emotional, and climatic desert of my dorm room, then I must not be able to do math anymore. After all, poor learning conditions never stopped me from learning math in the past. I was failing. I felt stupid and brokenhearted. I never imagined you being the hardest part of my day.

So I left. I knew that if our love story was supposed to go on, I would find you again.

And I did. I found you a few months later in the fall when I gave Multivariable Calculus another go after dropping the class the first time around. I was so nervous to give you another chance: “What if you, Math, are not the love of my life, and our time together is truly over? Then what do I do? Who am I supposed to be?” These questions kept me up at night. Nevertheless, slowly but surely, I made my way back to you. I remembered why I first fell in love with you, how I would call you “my art form, my muse, and my best chance at understanding how the world works.” I leaned into your beauty and removed the pressures of “What are we?” to focus on getting to know you again. In doing so, I learned and fell for multivariable calculus. I was able to get out of my head enough to see you the way I used to—as a gift and as an art, rather than as some people’s most unbearable form of torture.

I grew to love you again as I made sense of your hyperbolas and spherical coordinates. This time, though, I understood better why most individuals do not view you the same way I do. Math, as much as I love you, you have not been portrayed in the best light. Some say you are unnecessarily confusing, unlearnable, that you are a cruel tool used to make us feel stupid. I beg to differ, as I find your marvelous complexity to be a beautiful language worth learning, in the same way as Latin or Sanskrit or French. Even so, those summer months had me agreeing with the masses about who you are for a little while. It is not your fault that you have this reputation, but the history of your past lovers tells the tale of gatekeeping, elitism, and inaccessibility. You were made to be a tool to better understand the truths of the universe, but not everyone learned how to love you, or even that they could, in the ways that I did.

I made it my mission from that fall semester onwards to work hard to show others that you are theirs to love, too. Since then, we have had so much fun together learning about commutative rings, bipartite graphs, and homotopy theory. We have worked together to encourage students who may feel like I did that summer, showing them they can get along with and even befriend you better than they ever thought possible. As I have learned, the root of the hatred you receive is not that people think you are neither interesting nor useful (even though some folks would agree with those statements). In reality, most people who hate you have not had the opportunity to get to know you in the right environment—one where they can see you as fun and creative rather than as someone whose facts and algorithms they must memorize.

Nowadays, loving you takes the form of showing the real you to students for whom doors will open if they can learn to understand you. Math, you and I have had ample alone time together, and I will continue to cherish and make time for you. But having seen you from the eyes of “non-math people,” I understand them and you better. I understand how you may come across as abrasive or harsh or pretentious at times. I understand your complexities and the secrets that you hold, and that your art requires precision, commitment, and appreciation of nuance and details. With proper devotion to you, anyone can learn all the secrets you bear. The number of people who love you does not make you—or your love—any less valuable. Some things are just too good to keep secret. The corollary of all of this, Math, is that teaching others to love you causes my love for you to grow exponentially. If we show all students how to love you and how to make meaning of your magic, then there is no limit to what we can achieve.

Love,

Ms. Ellie