Scrolling through his Instagram feed, Leo Selvaggio, a senior specialist in creative technologies for the Brown Arts Institute, came across a post by the Creative Reuse Center of Rhode Island — a local organization that upcycles arts and crafts materials. After looking across the room at a new sewing machine in Multimedia Labs @ Brown, he decided to take a quick field trip for fabric.

That field trip turned out to be much more than a mid-afternoon recess. Selvaggio’s visit precipitated a chain of fortuitous discoveries, including several tubes of film with photos of the Moon’s surface.

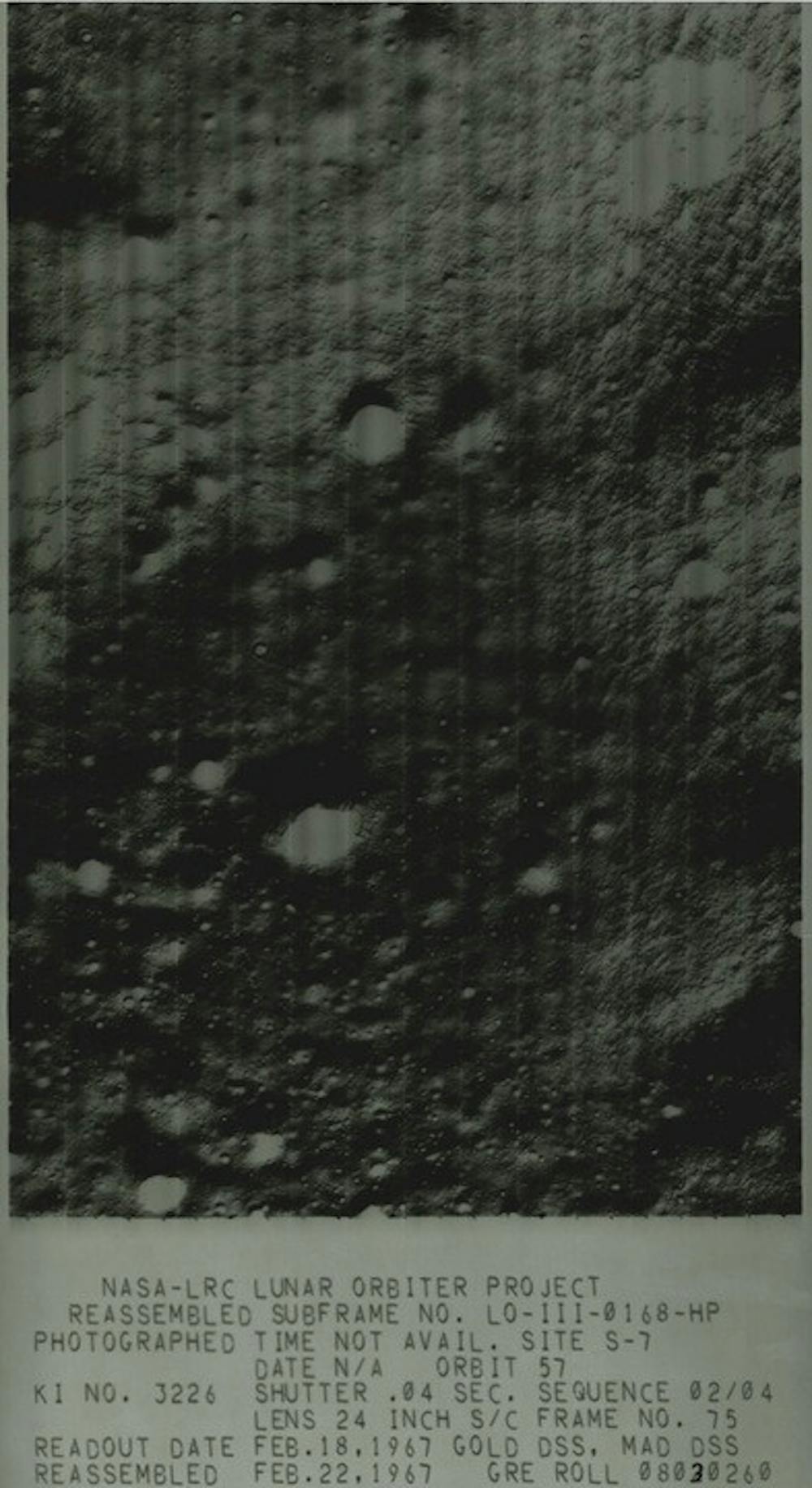

Originally part of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s Lunar Orbiter 4 Mission, the film negatives are now being used by students to create unique projects of their choosing as part of the MMLs’ Moon Design Challenge.

On his trip to the CRC in East Providence, Selvaggio brought along Kelly Egan, BAI’s associate director of creative technologies.

Upon reaching the CRC, the duo was over the Moon with excitement as they sifted through boxes.

“We kind of just went to explore,” Selvaggio said. “We didn't really know what to expect.”

The CRC officially opened late last year, continuing the spirit of Recycling for Rhode Island Education, which had previously provided Rhode Islanders with affordable materials and upcycled inventory.

Striking gold — or Moon rock

Selvaggio noticed Egan in the back corner, standing by a “mountain” of tubes, or what Selvaggio thought was a pile of rolled-up prints.

“‘What’s going on?’” Selvaggio recalled asking, walking over to Egan.

“I think these are all giant prints taken from a lunar satellite,” Egan responded, pointing to the black tubes lined in the corner of the Center. Egan began unraveling rolls upon rolls of film negatives, all capturing the Moon’s surface — craters, mountain ranges, valleys and all.

Noting their backgrounds in photography, Selvaggio told The Herald, “We're just sitting there like: ‘Oh, my god. This is a goldmine.’”

Selvaggio and Egan eagerly purchased several rolls of the film.

“We selfishly bought some for ourselves,” Selvaggio said, “We were going to hang them in our respective … homes.”

But the duo also decided to buy an extra roll for the Multimedia Labs. “We bought it not really knowing what we were going to do with it,” Selvaggio said, noting that the MMLs have “many artists from … different backgrounds, not just in the arts itself, but biologists, doctors, engineers.” The question at hand was how to get people excited about the film.

“We just thought, ‘What about a design challenge?’” Selvaggio said. “A prompt, like ‘Take this, do something cool, whatever your creative thing is — if it's painting, if it's sewing, if it's whatever,’ and we just kind of built it from there.”

The next week, Selvaggio and Egan made the film negatives available to students and sent out a Today@Brown announcement about the challenge. Since then, the duo has made multiple trips back to CRC to pick up new films.

“We’ve gotten a lot of people that have taken Moon prints, but we have not seen a lot of results of the challenge yet,” Selvaggio said. “And we’re okay if we don’t see any.”

“I think for some students, it might just be about actually having the object — like touching something that is twice as old as them,” he added.

Selvaggio participated in the Moon Design Challenge himself, sewing together various film negatives into a collar meant to mimic ones worn by astronauts. He also noted other submissions that are highlighted on the MMLs’ Instagram page.

The film’s origins

James Head, professor emeritus of earth, environmental and planetary sciences and geological sciences, said the film is likely from Lunar Orbiter Program missions.

The Lunar Orbiter Program consisted of five missions between 1966 and 1967 to photograph various points on the Moon. The objective of these missions was to identify smooth and level areas on the Moon’s surface that could be used for the Apollo program’s landings.

For each mission, NASA sent “unmanned spacecraft” to orbit the Moon, taking photographs.

He then noted the lines running across the film negative, which are remnants of the image-reconstruction process.

Lunar orbiters, which were often referred to as “drugstore(s) in orbit,” featured a camera that, once it took a photo, developed a film picture, similar to a Polaroid. Then it would scan the photo in horizontal portions and “form that into a signal to send back” to Earth.

Back on Earth, analysts organized the horizontal portions, reconstructing the photo.

Since 1968, Head has been extensively involved with NASA, where he participated in the selection of Apollo landing sites, planned and evaluated Moon experiments and provided preliminary analysis of lunar samples, among other tasks. Head has also contributed to a variety of international space projects.

The Moon’s features, according to Head, can tell scientists a lot about various aspects and timelines of the Earth’s development.

“Not only can we look at them in detail on the Moon, because the record is still there,” Head said. “But we can also infer a lot about what was going on in early planetary history and in the same vicinity as the Earth.”

“How do we do that? We take pictures,” he said.

Shining light on the film’s origins

According to CRC Founder and Director Elizabeth Ochs ’07.5, the film negatives aren’t too far from home: For years, they were the property of Brown’s Department of Earth, Environmental and Planetary Sciences. In June 2023, Brown DEEPS Communications Specialist Mae Jackson emailed the Creative Reuse Center, organizing a donation of the film negatives, which were being decommissioned by the department.

In an email to The Herald, Jackson confirmed that “most of the scans were from the NASA IV Lunar Mission.” The mission was launched in May 1967 and took 199 dual-frame exposures over 15 days.

“They were once part of the Brown/NASA Northeast Planetary Data Center, a repository of NASA materials and resources housed in Brown (DEEPS),” they added.

Jackson noted that the film negatives were deaccessioned during the department’s “larger organizational and consolidation efforts” this year.

According to Jackson, DEEPS hoped that via the CRC, “local educators and artists would use the material in their classrooms, science projects and other creative endeavors.”

“We were surprised and delighted to see some of the scans turn up back at Brown,” Jackson wrote.

“It’s about that principle of finding something to create in rubbish or in what was discarded,” said Mindi Schneider, lecturer in environment and society and a volunteer at the CRC. “Keeping things close to our hearts keeps them out of the landfill.”

The Moon Design Challenge “is our ideal scenario,” Ochs said. “Someone is inspired by a material, and they encourage others to become creative and they build community around that creativity.”

“To me, there (are) huge intersections with art and science,” Head added. “The bottom line is that science is just simply the exploration of the unknown. That’s it.”

“Art is an essential part of being human,” Ochs said. “It’s an act of creation, which we all do, whether we call ourselves artists or not.”

Tom Li is the editor-in-chief and president of The Herald's 135th editorial board. He is from Pleasanton, California and studies economics and international and public affairs. He previously served as a metro editor, covering the Health & Environment and Development & Infrastructure beats, and has worked on The Herald's copy editing, editorial page board, design and podcast teams.