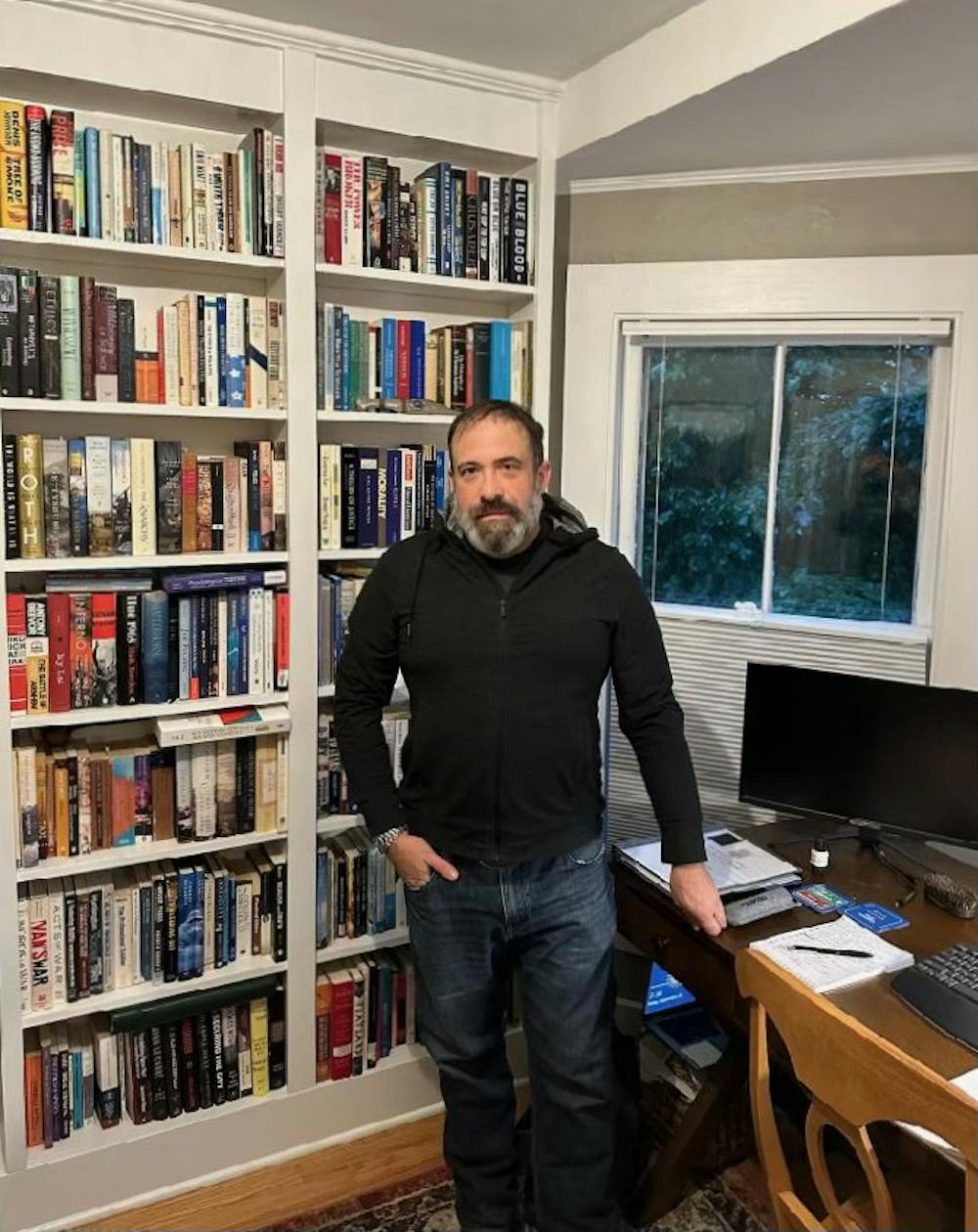

Overdose prevention centers are not associated with significant increases in crime or disorder, challenging safety concerns surrounding the sites, according to a recent study co-led by Brandon del Pozo, assistant professor of medicine and health services, policy and practice. The study examined the first government-sanctioned overdose prevention centers in New York City, both of which are operated by OnPoint NYC, a nonprofit dedicated to harm reduction.

The East Harlem and Washington Heights sites originally served as syringe service programs, providing access to sterile equipment for substance use and resources to prevent overdoses, such as naloxone, fentanyl test strips and information for addiction recovery. In November 2021, these two sites were converted into overdose prevention centers — locations where individuals can consume illicit substances under the watch of trained professionals to lower the risk of fatal overdoses.

The findings may be significant for Providence, which is poised to open the first state-sanctioned overdose prevention center in the country in 2024, The Herald previously reported. In 2021, Rhode Island became the first state in the country to legalize safe injection sites.

“To the extent that more research provides a better understanding of overdose prevention sites, it will help guide the costs, benefits and tradeoffs of policy-making, including when, where and how to open them,” wrote David Mitre-Becerril, assistant professor at the University of Connecticut School of Public Policy and a collaborator on the study, in an email to The Herald.

The Providence facility will be led by Project Weber/RENEW, a Providence-based nonprofit for harm reduction, in partnership with CODAC Behavioral Healthcare, a nonprofit supporting substance use recovery. The location for the center is still in the process of being finalized, according to Annajane Yolken, director of programs at Project Weber/RENEW.

According to Yolken, del Pozo’s study is important in supporting the development of the new center. “This evidence has helped Rhode Island take the bold and important step of sanctioning these facilities as a way to save lives,” Yolken wrote in an email to The Herald. “While we were not surprised by these results, we are grateful to have more evidence — especially evidence from the United States — to support our efforts.”

Del Pozo, Mitre-Becerril and collaborator Aaron Chalfin, associate professor and graduate chair of criminology at the University of Pennsylvania, observed crime trends in the immediate neighborhood of the centers and surrounding areas. The researchers used five administrative data sets in the NYC Open Data Portal, including criminal complaints, arrest reports, criminal court summonses, 311 calls and 911 calls. They measured overall changes in crimes reported after the installment of the site.

According to Mitre-Becerril, finding an appropriate control group was important for identifying potential changes in the community after the opening of the sites. The team used 17 state-authorized syringe service program sites in New York City as a control group.

“We also (tested) the robustness of our results to two alternative control groups using other areas with similar levels of violent crime and drug arrests,” Mitre-Becerril wrote. “All the results lead to the same conclusion: Opening the overdose prevention sites did not increase crime measured by reports done to the police or 911 and 311 calls for service.”

Del Pozo emphasized the significance of studying sites with previously established harm reduction programs.

“These are neighborhoods with acute needs, and those needs had been met with long-standing service provision from syringe service programs,” del Pozo said. Opening the overdose prevention centers “did not change the social ecology of the neighborhood in a way to cause things to get worse for neighbors and other residents.”

Along with finding no statistically significant increase in crime rates, the researchers observed a noticeable decline in low-level drug enforcement in the neighborhoods surrounding the centers, as measured by the number of drug possession arrests. Del Pozo called the relationship between the New York Police Department and the centers “collaborative” and “mutually respectful.”

“Our study suggests that a cooperative relationship between law enforcement and public health advocates is key to enhancing life-saving intervention without negatively impacting the community,” Mitre-Becerril said.

In August 2023, federal officials threatened to close the sites in New York City, which remain illegal under federal law. Even more recently, New York Gov. Kathy Hochul declined to allocate money from the state’s opioid settlement funds to the prevention centers.

Del Pozo noted that the “political hesitation to opening sites” is largely prompted by the concern that sanctioned criminal activity “will somehow metastasize into increased illegal activity around the sites.”

The study will “foreclose all these debates and discussions about crime and channel them towards how we (can) incorporate this into the most effective overdose response strategy,” he added.

Del Pozo added that researchers should investigate how the sites affect the behavior of substance users who have access to the sites compared to those who do not.

“This is not a crime intervention,” del Pozo said. “This is a health intervention.”

Sophia Wotman is a University news editor covering activism and affinity & identity. She is a junior from Long Island, New York concentrating in Political Science with a focus on women’s rights. She is a jazz trumpet player, and often performs on campus and around Providence.