This fall, the Brown University Herbarium welcomed back a piece of the University’s history: mushrooms pressed onto paper.

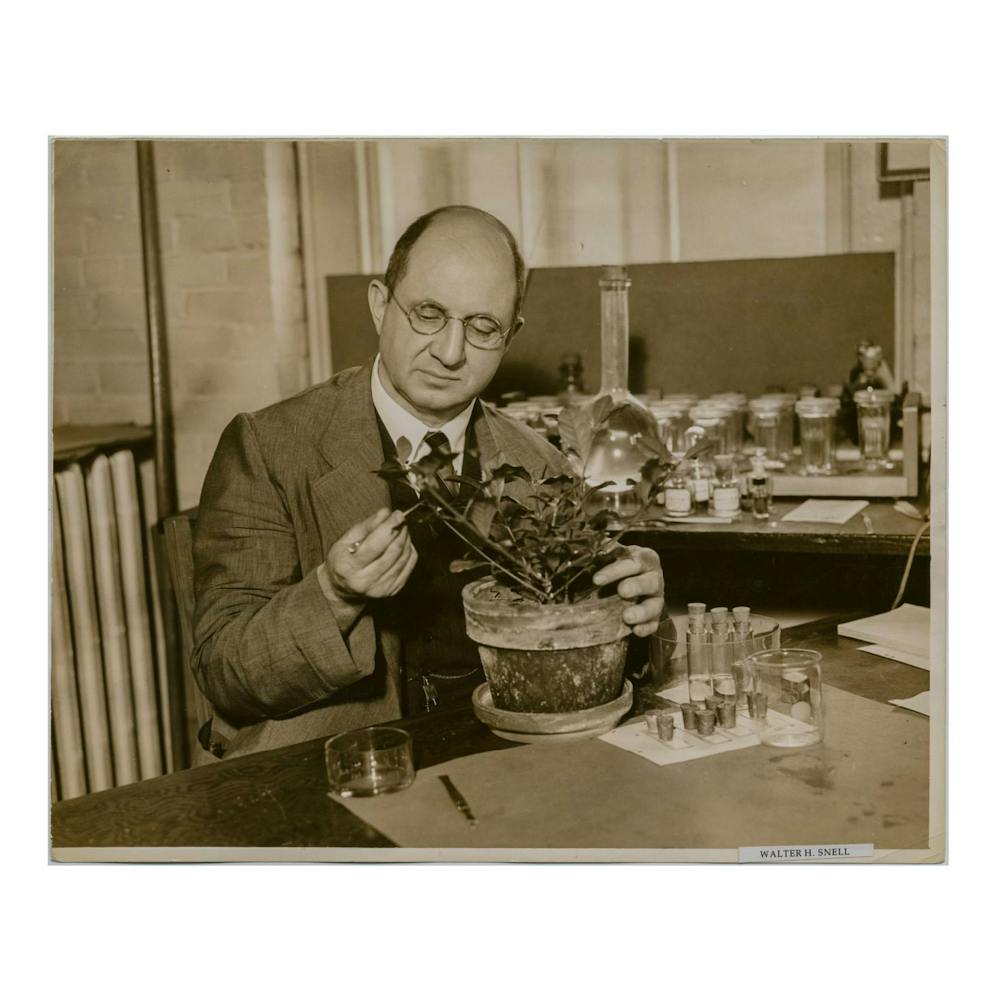

Tucked away inside the boxes — overflow from the University of Rhode Island’s herbarium — were the collections of former Brown professor, pro baseball player and botany luminary Walter H. Snell, class of 1913.

Snell was integral in mycology — the scientific study of fungi — and a notable figure in Brown’s history. But the decades-in-the-making homecoming of Snell’s mushroom masterpieces also signal a leap in the biological diversity of Brown’s cherished herbarium.

“Having these specimens incorporated into our database and being able to make them available to people is really important,” said Rebecca Kartzinel, director of Brown’s herbarium, interim director of the Plant Environmental Center and lecturer in ecology, evolution and organismal biology. “But I love the history of having Snell’s work back here.”

From URI to Brown

It started when the URI Herbarium ran out of space.

According to Keith Killingbeck, professor emeritus of biological sciences at URI, the university’s herbarium has two rooms: one that houses its more than 12,000 specimens and a smaller room that stores dozens of boxes. URI is converting the smaller room into an office space. That compelled Killingbeck to search for a new home for an overflow of 49 boxes of plants and fungi.

Brown — with the closest herbarium to URI, a large collection of Rhode Island specimens and an active staff — was the perfect home for URI’s extra specimens, Killingbeck said.

He contacted Kartzinel, and she traveled to the herbarium with Martha Cooper, curatorial assistant for Brown’s Herbarium, to determine if the specimens would be significant additions.

“It was a very big and exciting acquisition for us,” Kartzinel said. The donated samples range from plants collected in the late 1800s to Costa Rican flora from the 1960s to other samples from Rhode Island — which the Herbarium is “particularly interested in.”

Over the course of multiple weeks, the boxes were shipped to Brown. There, they were frozen for about two weeks to get rid of any insects and bacteria, Kartzinel said.

Since the specimens inside the boxes had not been cataloged, Kartzinel and Cooper had to go through the boxes themselves, most of which were “fungal specimens,” Kartzinel said.

“We noticed the name Snell came up a lot,” she added. “When I Googled him, I realized his name sounded familiar because he was a professor at Brown.”

And not just a professor: He was a Brown student athlete, a notable figure in the advancement of mycology and a professional baseball player.

Snell at the University

Snell was a professor of botany at the University from 1920 to 1959, according to his Encyclopedia Brunoniana entry, chairing the department nearly the entire time. He was responsible for establishing the University’s fungal collection, according to David McLaughlin PhD’62, emeritus professor at the University of Minnesota and a fungi curator. McLaughlin wrote a short biography on Snell in 1983.

“He did this mushroom field work at a time when there was no color photography to capture the colors, which are important for identification of these fungi, so he taught himself to paint them in watercolors,” McLaughlin wrote in an email to The Herald. “These paintings became a major part of his book on the boletes of northeastern North America and his “Glossary of Mycology.”

The book was a “culmination of his life’s work,” co-written with Esther Dick, class of 1931, another Brown professor and Snell’s wife, Kartzinel said. The watercolors are “beautiful,” she added.

Along with contributing to the understanding of mushroom groups and plant diseases, Snell was also the vice president of the Mycological Society of America during the second World War and a Major League Baseball player.

Snell served as a baseball, football, basketball and soccer coach for Brown for many years in addition to his position in the botany department, according to the Department of Athletics website. In a 1943 Herald article, Snell was identified as “one of Brown’s greatest athletic figures.”

McLaughlin worked for Snell as both an undergraduate and graduate student. “He was a very important mentor for me, and it led to a 50-year career in fungi and to becoming a curator,” he wrote.

According to McLaughlin, Snell was “a gifted storyteller and always had an amusing story to tell. … He often talked about catching for Babe Ruth during his baseball career. ” He said that he still uses Snell’s glossary on a regular basis.

In 1979, Snell’s fungal collection was donated to the mycologists at what was then URI’s botany department.

This semester, those same fungi returned to Brown.

The future of the collections

Kartzinel said that it will take several months, if not years, to organize all of the specimens. That process includes filing them in the databases, taking images and mounting certain specimens onto paper.

“We welcome anyone who is interested in working on the project,” Kartzinel said, including students to help file and organize specimens.

Kartzinel said one of the herbarium’s recent missions is to document the “flora of Rhode Island” to assess how the state has changed over time and get a “good snapshot” of what the state’s specimens have looked like during this time period.

“We think that this was the best outcome for these so-called ‘orphan specimens,’” Killingbeck said, referring to the flora being transferred to Brown. “I’m just really pleased.”

Robayet Hossain is a Science and Research staff writer focusing on up-and-coming research and departmental updates. He is a first-generation sophomore from Bangladesh and graduated in New Orleans. He loves listening to a variety of music genres and reading horror stories just to have problems falling asleep.