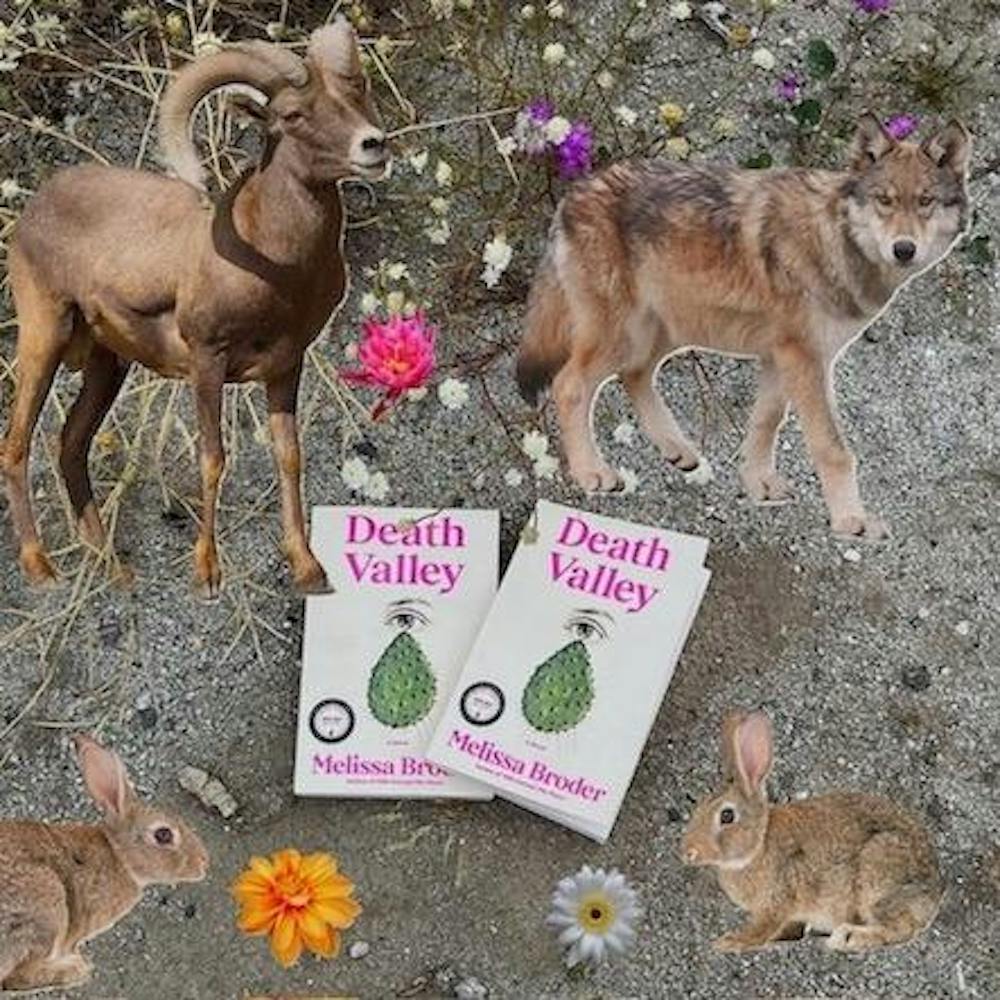

The protagonist of Melissa Broder’s newest novel “Death Valley,” published Oct. 3, travels to the Mojave Desert under the pretense of conducting research for a novel of her own. In reality, she is attempting to avoid several personal tragedies: her father’s third month in the ICU, her husband’s undiagnosed immune disorder and her unabating tendency to self-sabotage.

“If I’m honest,” she says, “I came to escape a feeling — an attempt that’s already going poorly, because unfortunately I’ve brought myself with me, and I see, as the last pink light creeps out into infinity, that I am still the kind of person who makes another person’s coma all about me.”

The similarities between Broder and her unnamed protagonist don’t stop at their careers. Both authors — real and fictional — are married to men with neuroimmune disorders that leave them housebound, identify as bisexual and have a sense of humor steeped in intense self-deprecation. Much of the dark humor in the novel expands upon the one-liners Broder posts on @sosadtoday — her account on X, formerly known as Twitter — which first catapulted her into fame.

Broder’s first publication was a book of essays titled “So Sad Today,” which dove “deeper into the psyche that made her a phenomenon as the dangerously irreverent” social media account, according to the back flap. She then became a novelist (“Death Valley” is her third) without losing sight of the voice that gained her followers. All of Broder’s work is preoccupied with the modern experience of dread, internet addiction, godlessness, political instability, climate change, self-hatred and loneliness — and the hilarious, existential humor that arises as a result.

In this new novel, Broder has managed to perfectly balance comedy and devastation. “People are such a commitment,” the protagonist says, just after admitting that she needs to talk to someone. “I would ‘reach out’ more often if everyone promised not to check in again later. That’s how they get you. Your tragedy = their ticket to texting every day. Then it becomes about their drama.”

This hilarious, honest and accessible voice remains strong throughout the book, but the plot can tumble into monotony. The stakes of the narrative do change (spoiler: The book suddenly becomes a survival adventure), but the motifs of the book (the desert heat, the father’s immobility, the oppressive despair) are introduced early and remain constant. Ultimately, the most interesting transformation happens exclusively in the mind of the protagonist.

Though the narrator is evidently stuck in patterns of self-belittlement, her grief for her dying father and sick husband is profound. Broder writes this struggle incredibly well — without cliché, and without swerving around the uncomfortable, selfish and usually unrevealed thoughts that accompany a loved one’s death. She creates a relatable narrative that neutralizes and investigates the experience of mourning.

The narrative effects of the novel are achieved with extreme skill: Broder is able to weave disparate experiences into one coherent story. One such moment comes when the protagonist is hiking through the desert, reconnecting with the earth and her own individuality as she texts her neurotic mother. She also FaceTimes her father in the hospital and debates whether to punish her husband; his illness is annoying her, which is only intensifying her guilt.

As she walks further into the desert, the protagonist spirals further into fear and delusion. Broder uses some fantastical elements without becoming unbelievable — including discussions with rocks, cacti and birds as her desperation increases.

While interacting with desert creatures, the protagonist remembers her father’s dumbfounded expression when she asked him if there was anything she could do for him. She realizes, then, that his reaction was not out of spite but out of confusion. She, his caring daughter, was already doing everything she possibly could.

Broder’s work asks readers to meditate on their relationships with others — on how selfishness and selflessness can and do interact. Her protagonist wonders: Is there anything anyone can do for anyone? And if there is, how can we make it happen?

Liliana Greyf is a senior staff writer covering College Hill, Fox Point and the Jewelry District, and Brown's relationship with Providence. She is a sophomore studying Literary Arts and a proponent of most pickled vegetables.