On Thursday, Oct. 19, approximately 40 students, professors and community members gathered in the Urban Environmental Lab to hear Leslie Acton, lecturer in environment and society, discuss her research on connections between people and coastal places. The lunchtime seminar was hosted by the Institute at Brown for Environment and Society.

Acton, a human geographer, grounded her research in her view of space and place. Space includes material objects, people and other organisms, she said, emphasizing that these are dynamic actors. Acton explained that she has also recently been developing an increasing awareness of the concept of place.

Place differs from space in that it is a “particular location, a particular spot that has clear kinds of markers to tell us this is a place of particular importance,” Acton said.

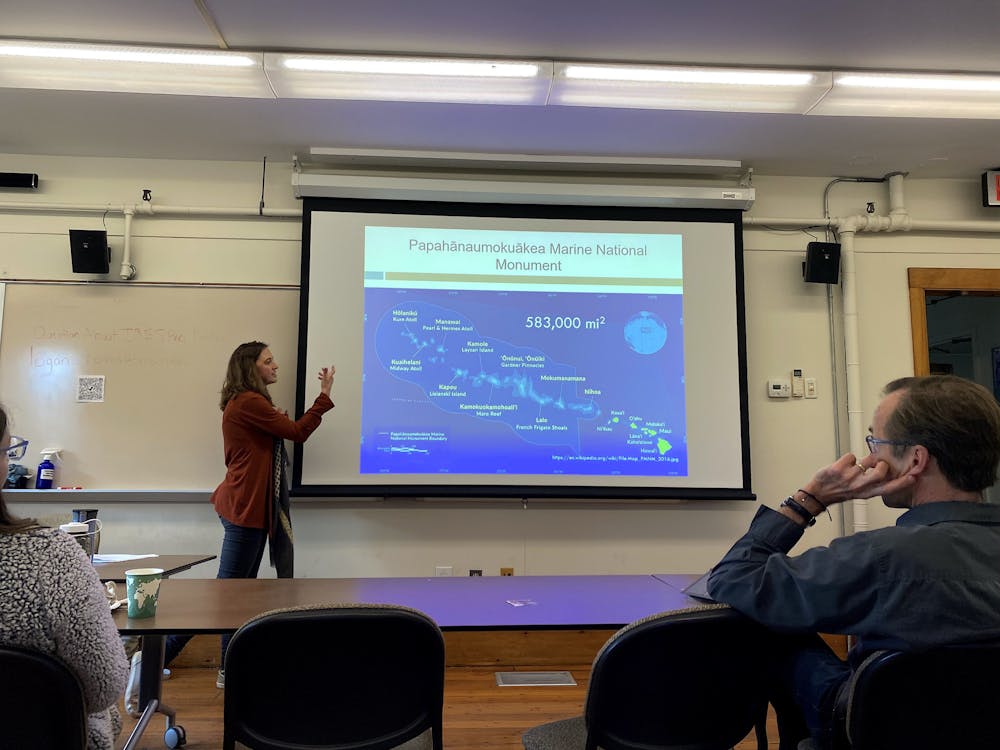

Recognizing place as important was relevant as Acton shared her analysis on the significance that the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument — 582,578 square miles of the Pacific Ocean holding ten of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands — holds to different people. She shared that this “marine protected area is touted as a big success story for … conservation in large part because this area has been protected both for its ecological importance and its cultural importance.” Acton added that, according to Native Hawaiian cosmology, the area is viewed as “where the gods and spirits reside.”

“As people pass on from this life, it’s where the spirits can continue to inhabit and live,” she said. “It’s a huge part of the cultural heritage.”

Along with Rebecca Gruby, professor of marine conservation at the University of Miami, and 'Alohi Nakachi, a doctoral candidate at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa, Acton researched the complex governance of the monument through the lens of polycentricity.

Polycentricity, Acton said, “is a theory that supports that if we have the many decision-making centers interacting and taking each other into account in particular ways, it becomes more likely to see these key kinds of governance benefits, including increased adaptive capacity, decreased risk of complete failure as well as increased ecological and social fit.”

According to Acton, the executive board of the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument is governed by federal and state agencies as well as the Office of Hawaiian Affairs — a “semi-autonomous state agency,” according to its website — which is meant to represent native Hawaiian interests. The organizational structure was established by a 2006 memorandum of agreement, according to the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument website.

“This is the first time that they have been in a governance complex on equal footing” to other agencies, Acton emphasized. She elaborated that this was significant because “many Native Hawaiians and allies understand, and it has been internationally, legally stated that the Kingdom of Hawaii is currently being illegally occupied by the United States.”

As part of her research, Acton interviewed 44 key governance actors, analyzed policy and conducted participant observation in key governance meetings. Acton’s team asked interviewees “how are you connected to the place of the Papahānaumokuākea?” Answers included reflections on the roles people play in governance, Native Hawaiian understandings of Papahānaumokuākea and physical visits to the place.

Acton’s research further analyzed the effectiveness of the polycentric governance structure and found that “the importance of meeting psychological needs of the governance actors was really really not there at the start.”

“In my interviews with people, particularly those who were there in those early years, trying to understand how to mesh these agencies that have totally different cultures, totally different mandates into each other was intense,” she added.

Acton’s takeaways centered around how the meshing of different perspectives affects understandings of place.

Separately, Acton has since started work on a four-year research project surrounding climate resilience that connects New England coastal communities with research institutions. The project focuses on four communities across Rhode Island and Maine.

Researchers from a variety of colleges and universities are coming together to “try to identify and measure changes in human health and well-being, habitability, the environment and other climate vulnerabilities to … try to predict impacts for planners.”

Fanny Vavrovsky ’26 attended the lecture and is currently enrolled in ENVS 0717: “Ocean Resilience: Ecology, Management and Politics,” which is co-taught by Acton. She is also involved with Acton’s research in New England.

Vavrovsky said that Thursday’s lecture and a previous IBES event made apparent “an actual path towards some kind of meaningful change that I can enact in the future.”

She also spoke to the passion of Acton and other speakers at IBES events.

“That’s a theme for all the IBES events,” she said. “These people are really cool, really engaged in what they’re doing, talking about projects that they actually care about and making an impact.”

Mikayla Kennedy is a Metro editor covering housing and transportation. They are a junior from New York City studying Political Science and Public Policy Economics.