Little girls' brains are sticky as flytraps. When you're young, every facial expression you see, every word you read, and the smallest fragments of information all collect in the back of your brain. These details combine to form a kaleidoscope of beliefs that color everything around you, distorting your world slowly, so that the warped lens gradually becomes your reality. This process takes place without you noticing, of course. But every so often, a certain piece of information lodges itself into your brain like a splinter, big enough that you’re conscious of it: an unintended insult from your best friend, a slogan from a soap advertisement, a warning from your grandmother. These extra-sticky pieces of information burrow themselves deep into your neural tissue like ticks in your skin, taking hold with barbed lips, and become foundational features of your world.

When I was 12, I read Salt to the Sea, a children's historical fiction novel about refugees in World War II. At one point in the story, several of the characters take shelter in an abandoned barn in the European countryside somewhere. There's one character, a refugee girl, maybe 18 years old, who is a nurse. She takes care of all the other sick and injured refugees in the barn, she never complains, and she remains kind despite the hardship she endures. Even now, I often find myself envious of the characters I read about in books, and when I read this one, I remember feeling bitterly jealous of this girl for how good she was. And then, the sticky line: another refugee describes her as "…pretty. Naturally pretty, the type that's still attractive, even more so, when she's filthy."

As if a peg had slid into place, goodness was suddenly inextricably linked to beauty in my mind. Long after I returned Salt to the Sea to the library, my imagination of this girl—her dusty face, her cracked lips, her bright brown eyes, her high cheekbones—followed me like a shadow wherever I went.

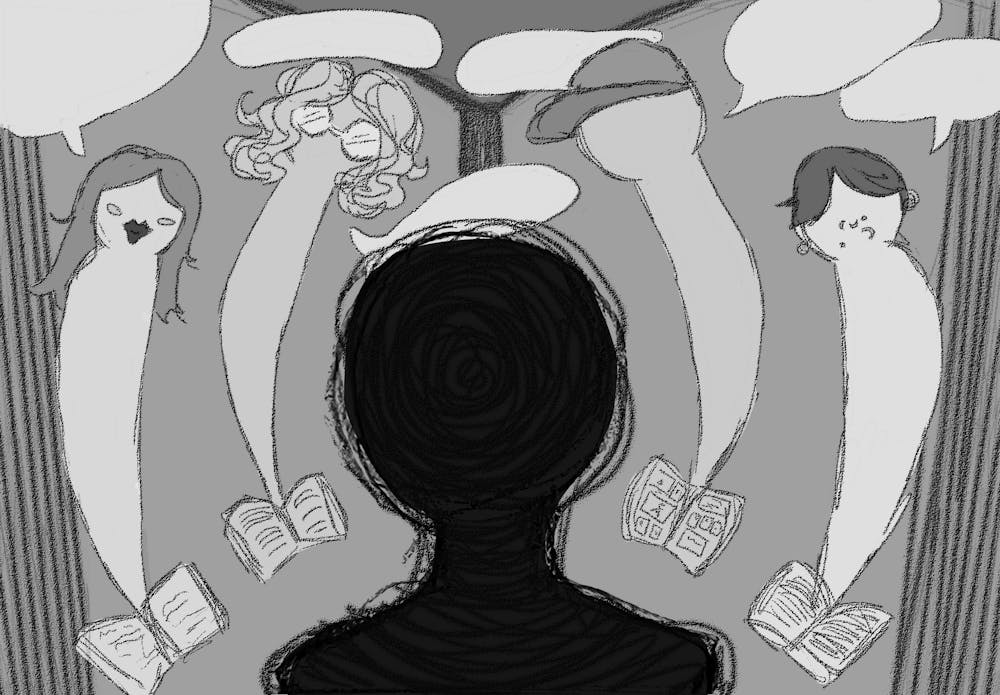

Except the girl's face changed all the time. When I read Harry Potter, she became a girl with curly hair, an encyclopedic memory, a commendable work ethic, and "thin ankles." When I read John Green, or The Perks of Being a Wallflower, she turned into someone ethereal and mysterious, with black bangs and piercings, with emotional baggage and a frailty that was visible from the outside: hollow collarbones, maybe, or snow-soft pale skin. In dystopian novels, she was always brave. She never admitted she was hurt. She was friends with the boys, and she could do anything they could do. She was athletic. She wasn't forthright with her emotions, because emotionality is vulnerability and vulnerability is unacceptable. She was always beautiful, and beautiful meant bright-eyed and innocent and so very small.

I took my study of how to be a good girl very seriously. When I was in sixth grade, Katniss Everdeen taught me that a heroine is athletic. I wasn't. So everyday when I got home from school, I stood with my dad in the front yard, and we threw a blue-and-orange foam football back and forth. He taught me how to release the ball with my fingertips still touching so that it spiraled perfectly through the air. I also started running; my mom took me to Wash Park on the weekend, and we ran-walked two and a half miles around the exterior path as I complained relentlessly. But my hard work paid off. That year, at recess, John Solomon threw a football out into the middle of the field and told me to go get it for him. I sprinted after the ball, picked it up, and tossed it back to him in a perfect spiral. He caught it and told me that I threw better than any girl he knew. I glowed with satisfaction.

The summer after sixth grade I went to a sleepaway summer camp, one with horseback riding and crafts and paddle boarding and group campfires. I decided I would use this summer to address a deficiency of mine, one that separated me from every heroine in every book I'd ever read: my normal-sizedness. I wasn't small enough to be the protagonist in my own story.

So I packed my favorite books—at the time, The Book Thief and Divergent—and, once I arrived, I signed up for a hike every single day of the summer. As I traipsed through the Rocky Mountain wilderness, I developed this peculiar compulsion to check my ankles every few steps to see if they had spontaneously narrowed. I absentmindedly circled my hands around my wrists to make sure my pinky and thumb touched. Near the end of the summer, I scaled Longs Peak, hiking from four in the morning to four in the afternoon. I returned to camp for dinner that evening, legs shaking and stomach twisting with hunger, and declined the bowl of spaghetti that a counselor handed to me, worried I'd undo all my progress from the day. When I returned home a week later, my uncle hugged me and smiled. "You look so good, Olivia. Did they forget to feed you out there?" And so it happened again. Another peg slid into place, another fragment of information lodged itself in my brain: Smallness is beauty; beauty is goodness.

Older girls' brains aren't quite as sticky as little girls' brains, but they can be stubborn too, holding onto things that other people might throw away. The heroines of the novels I read now have new, more nuanced characteristics for me to idolize. The Secret History, Memoirs of a Geisha, My Brilliant Friend: The female protagonists of these books have an air of transience, of mystery. They're brilliant and elegant and impossible to pin down. Most importantly, they aren't emotional. Emotionality is vulnerability, and a female hero isn't vulnerable.

I don't realize I've absorbed this quality until I'm sitting in a coffee shop across from a man I've met a few times and he says, "I hate it when girls cry. You strike me as someone who doesn't cry," and I take a twisted sort of pride in that judgment. It’s not an accurate one, but it’s exactly the way I want to come across. I realize again on a restaurant patio with an acquaintance, sipping on a margarita, as she's telling me about her anxiety. I can feel an I'm anxious too bubbling up inside me, but when it reaches my vocal chords it transforms into an I'm sorry, and the possibility of a deeper connection flickers and extinguishes between us.

I think my parents loved that I read so much as a kid. A little girl who reads isn't outside falling off a skateboard and skinning her knees; she isn't drinking vodka at an unsupervised sleepover; she isn't sneaking out to kiss boys in the middle of the night. But growing up in a world of imaginary girls comes with its own cost. Your role models become two-dimensional versions of people, so you too become flat. You sit up straight and you don't wear too much makeup because you must be naturally pretty, the type that's still attractive, even more so, when she's filthy. And you're just closed-off enough that the boys think you're "enigmatic" and the girls think you're kind of cold. And when you feel powerful emotions, you let them wrap around your lungs until you can't breathe, keeping a small, reticent smile on your face because emotionality is vulnerability, and vulnerability is unacceptable.

But now I see, at least, the flaw in my perception of the world and in my perception of myself. Day by day, I'm learning to direct more attention outward. The real girls I know, the ones I look up to, are emotionally vulnerable. They're funny and unabashedly opinionated, and they're kind without putting other people first every time. They aren't afraid to take up space. Nothing about them is small or frail. And I may never completely dislodge that deep splinter in my mind, the belief that a girl should be mysterious and beautiful, that I should be these things because the characters I grew up reading about were. Little by little, I've started to push the heroines of my childhood toward the back of the shelf, allowing myself to learn from real people and experiences instead—trying to expand rather than shrink, to make room for imperfection.