In 2019, a team of researchers based at Brown and the University of Minnesota launched the HerbUX project, The Herald previously reported. Focused on making digital herbarium collections more accessible, the team spent two years working with industry professionals and surveying community members to understand the strengths and weaknesses of current interfaces. Now, they are proposing novel approaches.

According to Patrick Rashleigh, head of digital scholarship technology services at the University’s Center for Digital Scholarship, the origin story of HerbUX dates back to 2012 when Tim Whitfeld, previous director of the Brown University Herbarium and now collections manager at the Bell Museum Herbarium, worked together on a display wall.

“We were looking for interesting things to do with the wall,” Rashleigh explained, “at the same time the University Herbarium was working with our digital repository” in order to digitize their collections and create high-quality images of the plant specimens.

Rebecca Kartzinel, current director of the Herbarium, lecturer in biology and assistant professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, explained that the process of digitization is an ongoing effort, as “herbaria all over the world continue to do this,” she said.

Kartzinel added that by creating online databases, both the general public and those pursuing biodiversity research can access the collections without needing to travel or going through the process of requesting very fragile specimens. The goal, she said, is to “mobilize what is held in cabinets.”

But those databases — or online repositories — can function in many different ways. The team observed that their interfaces are mostly “geared towards people who are experts in the field,” Rashleigh said.

“We thought that if we were able to propose a really user-friendly interface,” Whitfeld explained, then students would be able to “access this huge trove of natural history collections in the world’s museums and universities and use this collective knowledge that has been built over centuries.”

Whitfeld added that part of their motivation was making the specimens “more useful as an instructional aid in classes that focus on things like biodiversity and climate change.”

For Kartzinel, it was also important to consider the experience of other users, such as science educators, museum professionals and community members. “The current state was really only serving one of those groups,” she said.

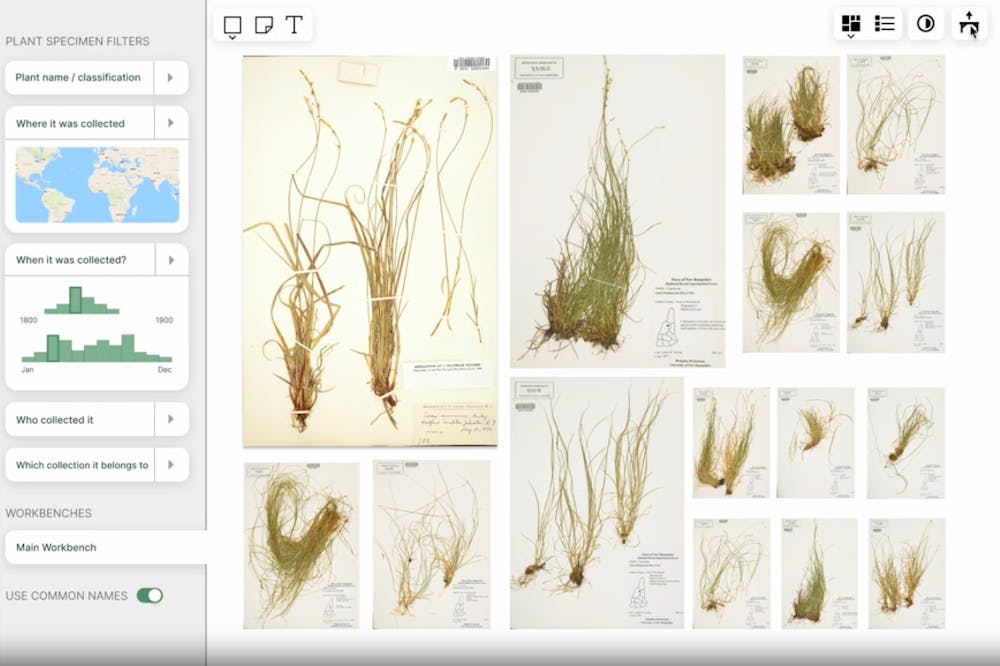

According to Rashleigh, most of the current herbaria interfaces operate in a system of “straight retrieval.” That means that when searching, users need to navigate a list, which usually only features Latin names and small thumbnails of the specimens.

Their guess, Rashleigh said, was that such a system failed to “leverage the qualities of the plant specimens which are easily understandable by anyone,” creating unnecessary barriers to engaging with the collection.

The team conducted three 90-minute conferences — which were moved to an online format due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Kartzinel explained — with herbarium and museum professionals and science educators. While each group had particular needs, they all shared a wish to make those interfaces more accessible and engaging, Rashleigh said.

After the workshops, the team was able to translate the needs of the groups into interface proposals. Rashleigh stressed that the interfaces they developed are prototypes — they are animations of what new interfaces could look like. They are, he said, “a conversation starter.”

Rashleigh explained that one of the main goals with the proposed interfaces was to translate the physical space of the herbarium into a digital product. To do so, they focused on making the interface function like a “workbench” — the “functional center” of any herbarium and a crucial “educational tool,” Kartzinel said.

“People were concerned, to a certain degree,” Rashleigh said, “that a virtual space would not convey what (it is like) to visit an herbarium.” To address that concern, the team highlighted functions that would allow users to interact with many specimens at once, arranging, stacking and manipulating them — “mimicking the physical handling of specimens,” Kartzinel said.

The tactile aspect of the interface is, according to Kartzinel, “the best part of” the proposal and what sets their project apart from existing interfaces. For Whitfeld, the proposed interface better captures the process of “discovery and exploration” experienced in the physical space of a herbarium.

During their workshops, the team also encountered a growing interest in making online repositories more interdisciplinary. To do so, Rashleigh explained, the team combined two ideas that are gaining traction in the digital world and the herbarium world, respectively: “linked open data” and “extended specimen.”

Within herbaria, the idea of an extended specimen refers to connecting a specimen to larger networks of educational fields, Kartzinel explained. Those interdisciplinary approaches, she said, “bring people in outside of basic botany,” adding that, in her experience, people tend to be very interested in the historical context of specimens, for example.

Linked open data would allow additional contextual data to be pulled from the internet automatically and shared with users, Rashleigh explained.

Beyond speaking with industry professionals, the team decided to put together a community survey to better understand people’s relationships with plants. While they highlight that the survey was “done almost on a whim,” Rashleigh said, they got over 400 responses in just a few days.

“Well, I’m a botanist: I love plants because I love plants,” Kartzinel said, explaining how useful the survey was to help her better understand the multiple multitude of interests that might lead people to engage with the herbarium and interface.

“People are interested in plants,” Rashleigh added. “That was something that came out loud and clear.”

While developing an interface themselves “would be a very different engagement,” Kartzinel said, it is not something the team rules out. “The next phase would actually be to build something functional and useful,” Whitfield added.

But, for now, Kartzinel said, the team needs to take a break and focus on other things.

For her, “there are multiple possible futures to this project,” and they are excited about serving as a resource for those building digital repositories themselves, Rashleigh added.

Julia Vaz was the managing editor of newsroom and vice president on The Herald's 134th Editorial Board. Previously, she covered environment and crime & justice as a Metro editor. A concentrator in political science and modern culture and media, she loves watching Twilight (as a comedy) and casually dropping the fact she is from Brazil.