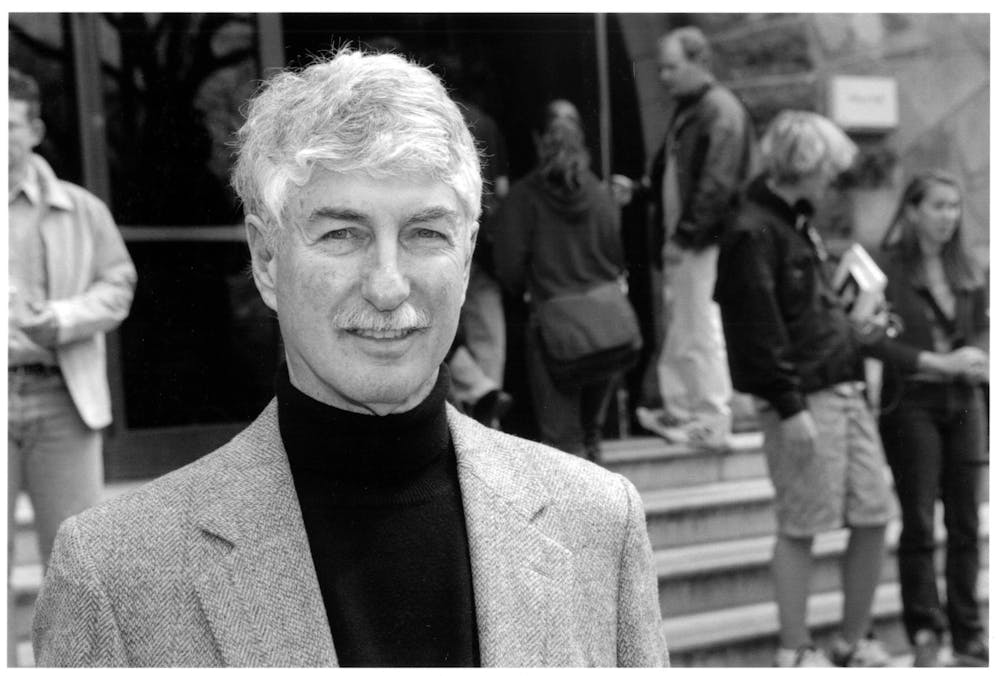

When Luiz Valente, professor of comparative literature and Portuguese and Brazilian studies, was asked to describe his lasting impression of his former teacher and colleague, Arnold Weinstein, professor emeritus of comparative literature, he reminisced on Weinstein’s kind, respectful and brilliant nature.

“He was a very charismatic teacher,” Valente said. “But not only that, he was someone who was really willing to listen. I wanted to be like Arnold Weinstein.”

Weinstein received his Bachelors of Arts in Romance Languages at Princeton. During his time there, he spent a year studying in Paris and a summer in Germany — experiences that fostered his love for both literature and comparative studies, Weinstein said.

“I developed a view that literature was not just about language,” he said. “It’s about human values, about human relationships, about all the things (that) resist any metric.”

Weinstein went on to earn his PhD in Comparative Literature at Harvard, where his chosen languages were French, English, German and Swedish. Almost immediately, he landed at Brown — where he stayed for 54 years before retiring last spring.

“There is a season for everything, including exit,” he wrote in a piece for Brown Alumni Magazine.

A new era of comparative literature at Brown

Following the completion of his dissertation in the spring of 1967, Weinstein accepted a job offer at Brown that began in 1968.

“My timing was impeccable, because that’s when … within a year, Brown became Brown (with) the new curriculum,” Weinstein said.

According to Weinstein, the comparative literature department was nearly nonexistent for undergraduates at the time. The new open curriculum allowed Weinstein to upend the comparative literature program — or lack thereof.

In the following years, Weinstein’s experiences with colleagues across departments at Brown and the country emphasized to him the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration,

According to Weinstein, one course called “Sacred and Secular” gathered professors from religious studies, philosophy and literature “who had totally different views about what a piece of literature is or why you would read” it.

Dore Levy, professor of comparative literature and East Asian studies, noted Weinstein’s efforts in bringing non-Western languages into the comparative literature department. “He was a visionary about the cultural inclusion in comparative literature,” she said.

According to Weinstein, international students from non-Western countries would often choose Western languages instead of their first languages, such as Chinese or Japanese, for their comparative literature studies. But studying in their birth language is “part of (their) birthright,” he said.

Moving past the existing confinements of Western languages in comparative literature allowed new professors — like Levy — and students at that time to find a home in the department.

Levy praised Weinstein for greatly expanding the scope of Brown’s comparative literature department.

“He was elegant, he was suave, he was sophisticated, but he was taking a big chance on expanding the department into Asian literature,” Levy said. “I don’t know any other (institution’s) department that has so many core faculty in non-Western literature.”

Impact beyond books

Jennifer Franklin ’94, Travis Landry ’97 and Eric Calderwood ’03 — former students of Weinstein who are now teachers and professors — also attributed positive experiences in the department and beyond to Weinstein’s contributions.

“For me, Arnold really defined what it was to be a college professor,” said Calderwood, who currently teaches comparative literature at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. “I think until I met him, I didn’t really even know what that was.” He added that Weinstein’s joint lecture-seminar mode of teaching created a “mesmerizing” experience.

In some class sessions, students and Weinstein would gather in an undergraduate’s off-campus home for discussions. “That was … very intimate and fun, in a different way,” Calderwood said.

What Franklin and Landry remember about Weinstein goes beyond their classes and even their time at Brown.

Landry’s relationship with Weinstein “did not end with graduation from Brown,” he said. “In some ways, that was the beginning.”

Landry, who teaches literature at Kenyon College, told The Herald that his experiences with Weinstein shaped him as a professor in the best ways possible. He said that he wants to instill in his students “a continuation” of what Weinstein has brought to him.

“What we took from this (class) aren’t all those close readings … but how they really helped expand our worldview, and our empathy and our compassion,” Franklin said. “The reason why I’m a writer is because of reading those texts and looking at them in the way that he encouraged us.” Franklin is a poet and teaches in the creative writing MFA program at Manhattanville College.

As he leaves the department, Weinstein said he hopes its courses continue to allow students of all backgrounds to read literature from a wide variety of cultures — even if that means classes have to be taught with translation and the discipline has to depart from its “esoteric” roots.

“Comparative literature is a field that should make sense to young people and should be taught in such a way that it makes sense” to everyone, Weinstein said.