“‘I dream backwards now. You won’t believe how backwards you’ll dream someday.’”

(Marina Keegan, The Opposite of Loneliness)

***

The first time I tried to use a washing machine in Champlin Hall’s fourth floor laundry room, I was oblivious to the fact that it was already broken. Fiddling with the appliance’s various knobs and fruitlessly swiping my credit card into the scanner meant for student IDs, I couldn’t help myself from thinking: “Wow. This is really different from how it is back at home.” Standing there in the tiny room under glaring white lights, I realized I felt lost.

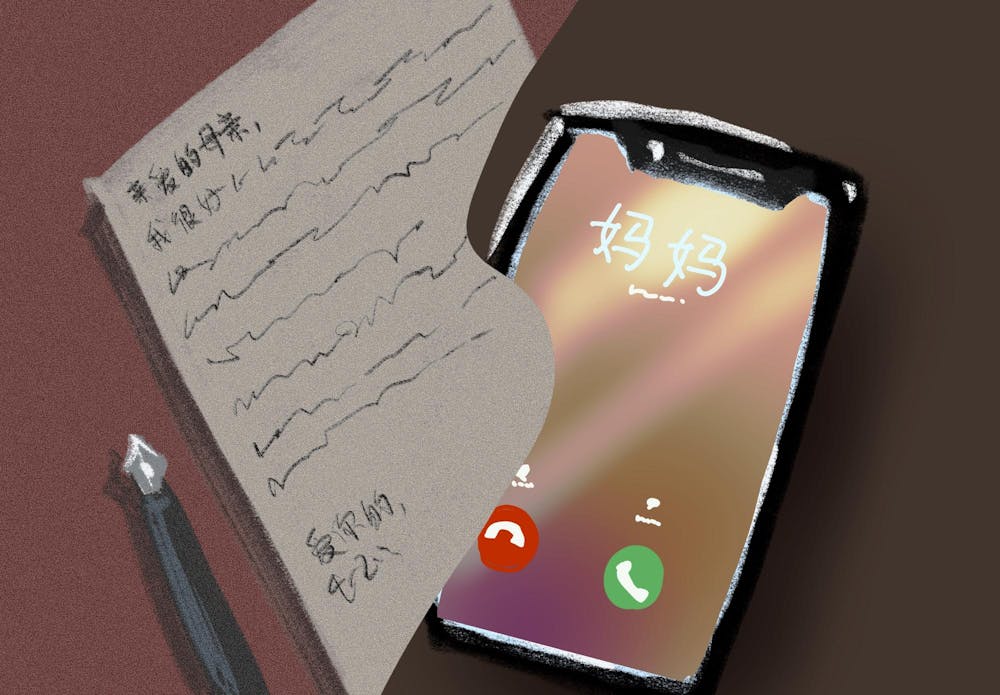

It wasn’t even the first time I’d been far from home. Before arriving in Providence, I had attended boarding school for several years, where I’d been away for months at a time. Yet somehow, things felt different. Perhaps I was preoccupied with the notion that starting college was greater than just a technicality, like the one that marked the step from elementary school to middle school. No, this was something infinitely more significant. Unlike at boarding school, where everything felt more relaxed, starting college marked the beginning of a brand new phase of life—of being. Starting college meant shedding the childish traits of high school and embracing adulthood. And there I was, allowing an experience as mundane as washing clothes to overcome me. Unsure of how to proceed, I did the only thing that felt safe. I called my mom. Within 10 minutes, the machine was churning happily, and I couldn’t have felt more relieved. Back in my dorm, I folded shirts and trousers with the improved, space-efficient method my mom had taught me a week prior.

My mother moved from the mining village of Fengfeng, Handan to Beijing in 1981 at the age of 17 to attend Peking University. Having lived in scarcity for her entire life, beginning a new chapter in a bustling city of over five million people must have been nothing short of terrifying, though exciting too. When I asked her about this, she agreed with a smile, laughing as she recollected the events of decades prior. She described how, armed with two tiny suitcases filled with all of the items she owned, she hugged my grandparents goodbye, boarded the train, and was off.

Upon arriving at her accommodations, my mother discovered that there was only one crank phone allocated to a building that housed over two hundred freshmen, all of whom were desperate to update their loved ones that they’d arrived safe and sound. Waiting in that never-ending line was time-consuming, but coming across other means of instantaneous communication, such as payphones, was virtually impossible at the time in China. My grandparents didn’t have many options, either. In fact, only an estimated 0.38% of Chinese families had access to a phone in 1978, and my grandparents, who lived in relative poverty, belonged to the 99.62%. To speak with my mother, they had to schedule trips to the community center, the only location with a public phone within a 20-mile radius. Planning these trips was also difficult: my mother had a busy schedule and infrequent access to the singular crank phone, which malfunctioned and broke after two weeks. My mother could either send her family a written letter, a process that could take anywhere from one week to three months, or she could wait until she next returned home and saw them.

My mother was forced to adapt to her new surroundings alone. There was no way to debrief her days with her father, or to cry to her mother when she felt particularly alone. Still, being as strong as she is, my mother adjusted quickly. She threw herself headfirst into her schooling of French and international relations. And while she didn’t necessarily find any overwhelming passion in these subjects, she grounded herself. She was working towards a greater goal—one that culminated in securing a career that would provide her with the means to move her parents out of their rural, impoverished village, to somewhere more comfortable. A place where they could finally relax. Yet despite finally coming to call her new environment a home away from home, and making the lifelong friends she still has today, she knew that something was missing. She missed her real home, her support system of 17 years. It was a feeling that no amount of newfound joy could wash away.

Things are vastly different now. Both my mother and I live in America, and both of us have smartphones. Communication between us is instantaneous. In fact, access to digital communication is a given for most Americans today, with about 95% of Americans owning a mobile phone in 2018. The rapid boom of technology over the past 20 years has been unprecedented, with the number of people with access to a mobile device growing exponentially. Now more than ever, it appears that digital communication has become the new status quo, with a new generation being taught to type and write simultaneously. This phenomenon is not exclusive to the Western world, but has spread across the globe. In China, over 1.03 billion people owned a mobile phone and accessed the internet in 2022, and this number is expected to increase to 1.2 billion by 2027. The differences between the era in which my mother started college and the era we live in today are both stark and undeniable. I’m able to contact my mother whenever I want, and yet, in boarding school, my messages home were few and far between. At the time, I felt that independence was synonymous with separation. I convinced myself that I was always too busy to call my mother, whereas the real reason for my silence was that I had created a rift between my school life and my home life.

But existence is multifaceted. I don’t need to let go of my “old life” in pursuit of new horizons. I’m lucky to have a supportive parent who cares about how I’m doing. So whenever I have a chance, I message her. I send her photos of my dorm as it gradually grows more and more decorated. I send her photos of the food, and she guesses which photos were taken at which dining halls. I send her photos of the scenery, of particularly beautiful mornings where the sun gleams onto the trees in a way that makes everything look blue and gold. Through my messages, phone calls, and photos, my mother has been experiencing college all over again, albeit through a far different lens. Instead of urging me to take the most intensive classes offered, as she pressured herself to do at my age, my mother texts to tell me that I should study whatever makes me feel best about myself. I am being given the opportunity to develop my love for what I love, while receiving an amazing education that she worked her entire life to provide me with. And I know that whenever I need support, the kind of support you can only receive from your people, I know that they’re only a call away.

As Keegan writes in The Opposite of Loneliness, my mother is dreaming backwards. She is watching a lifetime of dreams manifest themselves in me, as I begin walking down the same path that she too walked down 42 years ago. The rapid advancements of technology may be unprecedented, but I can personally testify that technology has succeeded in one thing: connecting people. The world now feels a little smaller, a little more tight-knit. I can take my mother with me on every exhilarating and enchanting step forward—something that she could only dream of doing with her own mother. Everyone is constantly embarking on new journeys that are lined with millions of past dreams. And now, we can venture far away without fearing that we’ll let go of who we once were. It’s a nice sensation, knowing that home can be tucked away in your jacket pocket. It’s like having armor. Armor that feels like the warm hug of freshly washed laundry.