An applicant to Brown with parents in the top 0.1% of earners are over 2.7 times more likely to attend Brown than one from the bottom 20%, according to data from a July study by economists from Brown and Harvard.

The researchers from Opportunity Insights — including Professor of Economics and International and Public Affairs John Friedman and Harvard economists Raj Chetty and David Deming — estimated the advantage that students from wealthy families receive in the admission process. They found that among all “Ivy-plus” schools — the eight Ivy League schools, along with Stanford University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Duke University and the University of Chicago — students from the top 0.1% are over twice as likely as the average applicant to be admitted, after adjusting for test scores.

The study relies on data from tax records and federal records of college students from 1999 to 2015, as well as standardized testing data from 2001 to 2015. At least three Ivy-plus schools, which remained anonymous in the study, additionally shared complete access to their admissions assessments.

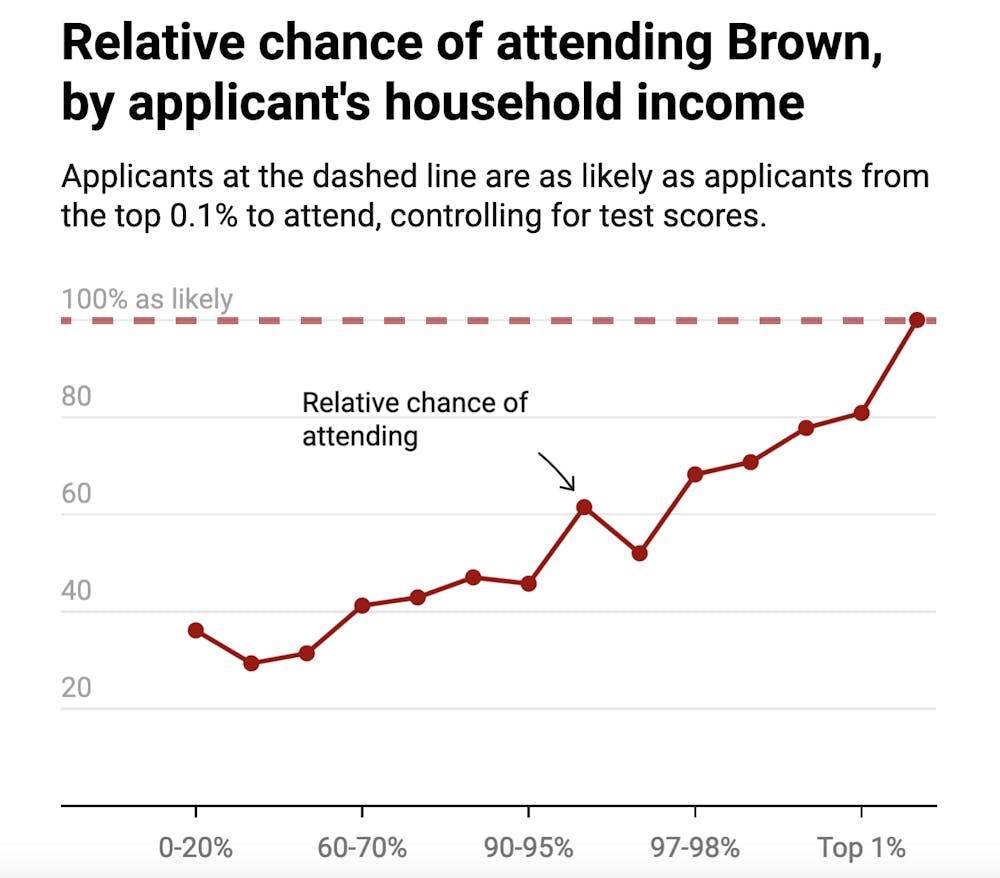

Though the researchers didn’t estimate admissions rates for specific schools by income, they calculated how likely a student was to attend a school if they applied. Students who were admitted to a given institution but didn’t attend were not counted. They calculated that measure — adjusted for test scores — for students from different income brackets.

At Brown, differences by income are vast.

According to the data, applicants to Brown from the top 0.1% are far more likely to attend than applicants from any other income bracket. Controlling for test scores, applicants between the 20th and 40th percentile for income are 29% times as likely as those from the top 0.1% to attend.

The research has two key takeaways, Friedman wrote in an email to The Herald.

First, the decisions that colleges make in shaping the admissions process — preferential treatment for legacy students, athletic recruitment and other, non-academic considerations — are the “largest factor driving the overrepresentation of high income students,” he wrote.

Second, because Ivy-plus graduates disproportionately occupy leadership positions in the country, colleges’ admission decisions impact the composition of America’s leaders.

Friedman and his Harvard colleagues built on research published in 2020 that found students from low-income families have “excellent long-term outcomes after attending selective schools, but that there are very few low-income students at these schools.”

Niyanta Nepal ’25, co-president of education equity group Students for Educational Equity, wrote in an email to The Herald the group was “in no way surprised by these findings,” adding that concerns about socioeconomic inequality in education “have been backing our campaigns from the beginning.”

Responding to the research, Nepal called for an end to legacy admissions — which allows college admission officers to consider whether an applicant’s family members attended the University. SEE has criticized legacy admissions and test-optional practices, arguing that the policies adversely affect campus diversity, The Herald previously reported.

For the University to continue practicing legacy admissions “would be a clear indicator that they have no intention to remaining equitable, but rather the financial gain is their driving factor,” she wrote.

Associate Provost for Enrollment Logan Powell wrote in an email to The Herald that the University has “made transformative commitments to financial aid in recent years, including the Brown Promise, need-blind admission for student veterans as well as need-blind consideration for all international applicants starting with the Class of 2029.”

The University’s admission office “does not have access to applicant family income data at any point during the selection process,” he added.

With additional reporting by Owen Dahlkamp

Neil Mehta was the editor-in-chief and president of the Brown Daily Herald's 134th editorial board. They study public health and statistics at Brown. Outside the office, you can find Neil baking and playing Tetris.