Through the queer rights movement of the 20th and 21st century — and well before — art has played a pivotal role in self-expression, activism and community-building for queer people.

To celebrate Pride Month, The Herald spoke with three student artists about how queerness impacts their art and how, inversely, art allows them to understand their identities more clearly.

Karen Hu: Seeing feelings and possibilities through art

Karen Hu ’24, a computer science and visual art concentrator, has experimented with several artistic mediums in college: painting, sculpture, math and screen printing.

When they first arrived at Brown, Hu was dealing with a lot of “personal” emotions towards her “internalized anti-queerness,” and painting became a form of release and honesty. “I was really drawing inspiration from my own life and mostly my feelings,” they said.

Later on, Hu’s art also took inspiration from mathematical concepts both requiring “very rigid definitions” and representing “an infinity of different options.” They noted that even though a two-dimensional plane needs a formulaic grid system to represent shapes, “in that plane of stuff, you can make any line, any shape.”

“There’s an infinity of options to be made within that grid that we’ve imposed,” Hu said, noting that a similar dynamic exists even in binary programming of computers — an infinite number of choices to make differently.

“To me, that felt very queering of math,” Hu added.

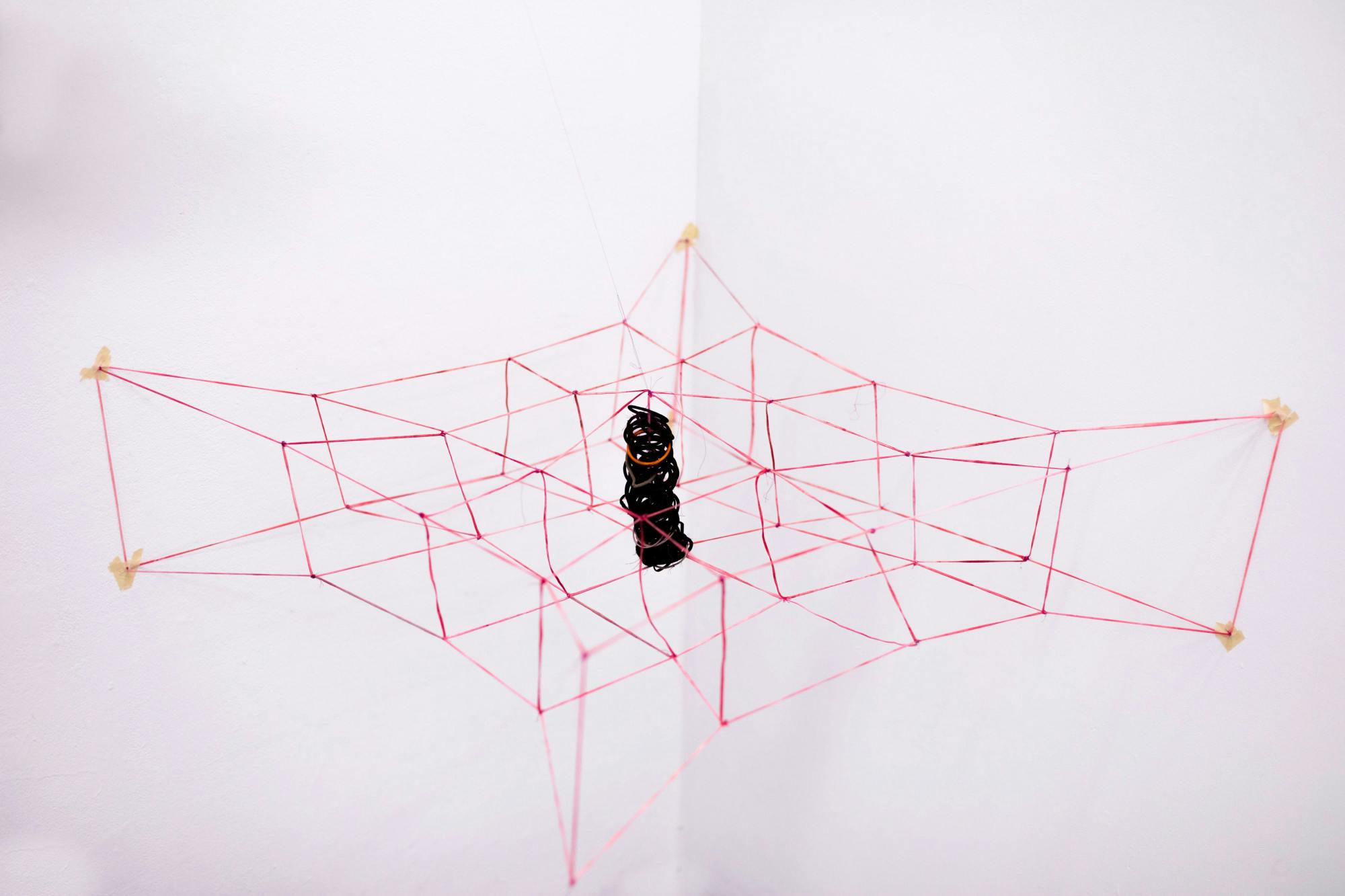

Those ideas, in turn, influenced her sculpture: One work they created is a net made of mask strings dyed pink. “In some ways, the net is very rigid,” like a grid, they said. “But because it was made out of mask strings, you could stretch it any which way, and it really is a malleable thing.”

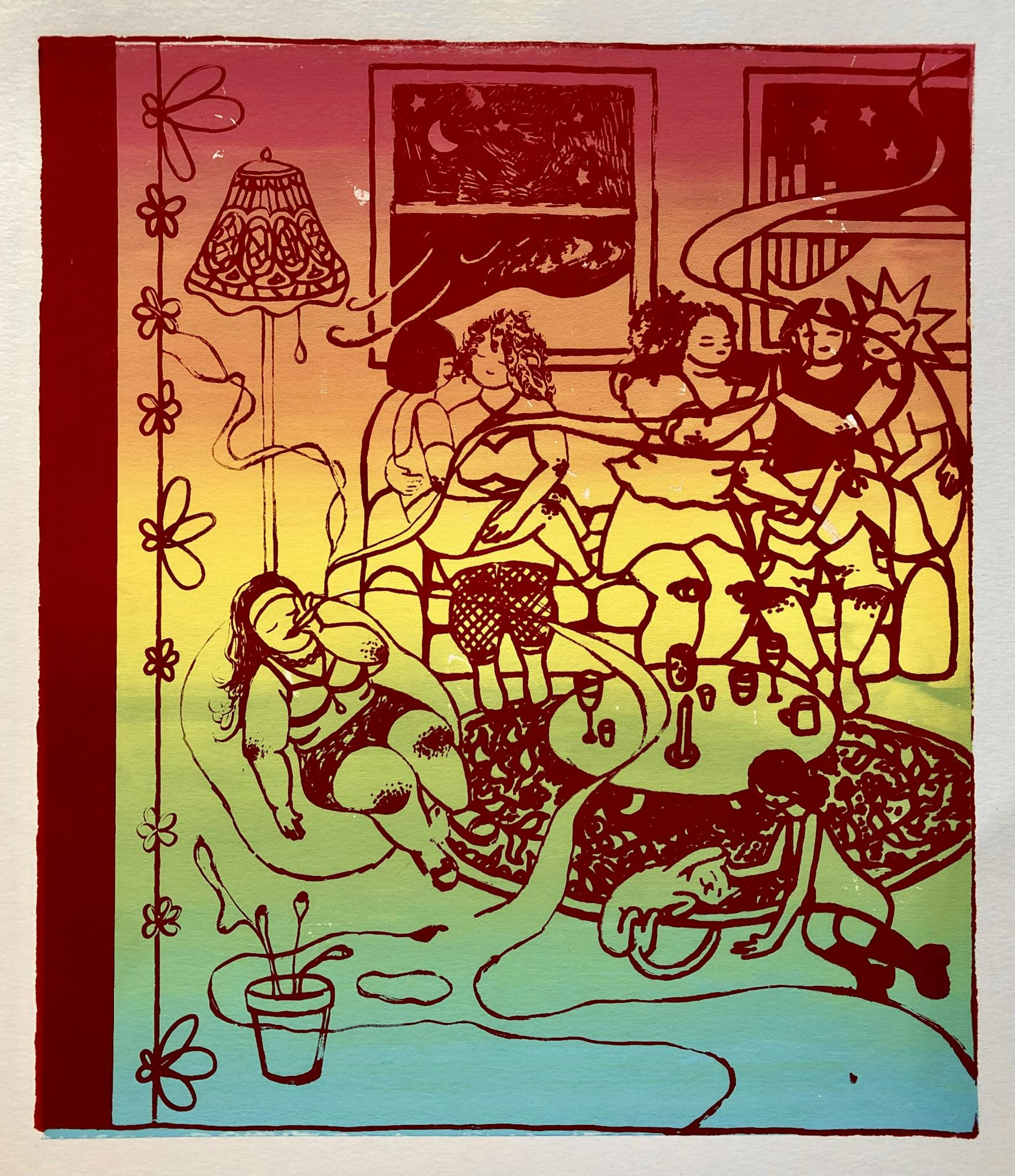

Recently, Hu has tried to bring feelings and experiences of “queer joy” in their life into screen prints. “I really like the medium of screen print,” she said. “How you can create multiple and spread information or aesthetics, or just spread that feeling further than just one physical object.”

Art began as Hu’s “therapist” in high school, when it was their outlet for “teenage angst.” During Hu’s first art-making phase in college, art was still the release of “feelings and pain.”

“But when I started to think about all the possibilities … and what I wanted to say and spread in the world … now my (art) is really about joy and envisioning the world that we want to have,” Hu said.

She added that art allows them to “say things and understand things about myself that sometimes I don’t really understand until after looking at the piece.”

Going through feelings of a painful end to a long-term friendship where there existed “homoromantic tendencies,” Hu didn’t realize that they were “actually mourning the end of (that) friendship” until many prints they made were about “letting things go … (and) end.”

Much of Hu’s artwork is directly inspired by their queer friends, she said.

Hu recalled a queer comics class when they mentioned to Meta Covington ’25 that whenever asked about gender, they feel that “a ball on legs” is a more accurate answer than a specific gender. Covington later texted Hu a self-created emoji of a soccer ball on little legs on iMessage.

“And I was like, like this is kind of an amazing motif. And I really (ran) with it a little bit,” Hu said.

Hu noted that they wanted to incorporate “more of a community aspect” to their artwork.

“Part of my mission as a queer artist is to spread the gay agenda, and I say that seriously,” Hu said. “I think there is a lot of good that comes from seeing oneself represented in artwork, or being able to connect your life’s experiences to an artwork.”

Alaina Cherry: Painting as a self-reflection of internal conflict

When cognitive neuroscience and visual art concentrator Alaina Cherry ’24 first started oil painting in the summer of 2020, she felt like she “finally found a medium that works for me and what I wanted to do.” That summer, she began to consider painting as something more than a hobby.

According to Cherry, a big part of her practice is color — “finding ways to use different colors to create a sense of realism.”

She added that her works focus on “intersections of identity,” striving to combat Eurocentric beauty standards and more broadly the ways in which racism and patriarchy impact Black and queer womanhood.

One example in her work is the use of magazine clippings in the background of her paintings to signal the looming influence of dominant culture.

“Usually, when I address Black queer womanhood in my art, it’s more self-reflective (and) introspective than a statement about black queer womanhood in general,” Cherry said. “It looks different for everyone.”

Cherry’s own experience and how she fits or doesn’t fit into a “white, heteronormative, patriarchal society” inspires her art. “I have always been really obsessed with portraits and faces,” she added.

“Learning about and reflecting on my identity as a woman and learning about ideologies of misogyny … have really opened my eyes to my identity as a queer person,” Cherry said. “I had to kind of jump over that hurdle (of internalized misogyny) before I even realize I could accept and give love and affection to someone the same gender as me.”

She noted that growing up “conditioned to be super boy-crazy,” she is constantly self-reflecting on “internal conflict” between her identity as a woman and a queer person, which are “so tied together.”

“In my paintings, it really is like a mix between” these two identities, Cherry said.

Completed right after a breakup with a boy, a piece where Cherry painted herself grabbing a fruit explores her queer identity, because she could “finally think about it.”

“I’m doing more and more things to express my queerness in my art, but I have to sell the things internally as I’m doing it.”

For Cherry, self-portraits force the artist to be “vulnerable” with themselves. As a person who is “reluctant to do journaling,” she would write to piece together her thoughts before doing a self-portrait, Cherry said. “I’ll be like, okay, how can I put these words into like a visual image?”

Cherry encourages everyone who is interested in making art to not be scared. She noted how much she loves the painting studio space: “It’s just so magical there,” she said. “I get so much inspiration and motivation to paint when I walk around and see all of my classmates’ and other students’ art pieces.”

Jo Ouyang: Art as a magical and transcendental experience

Growing up in Georgia, Jo Ouyang ’26 finds it unique to be from the American South, where there exists “a specific heritage and history for white Americans.”

“But, for me, as an Asian American living there, I’m contending a lot with what it means to be American,” they said. “And what it means to be in this land that has been settled and colonized, and to be an immigrant there.”

A dual-degree student concentrating in ethnic studies at Brown and painting at the Rhode Island School of Design, themes of Ouyang’s oil paintings focus on nature, their “relationship to land” and futuristic world-building for a “more radical, more equitable” planet.

They spend a lot of time in nature — trips with friends to beaches in Rhode Island, sitting on the creek in their backyard in Georgia — and draw “a lot of inspiration from the things that are already happening around” them, said Ouyang.

A passionate photographer who “takes photos all the time” in their “daily life,” Ouyang captures things that interest them to later recreate them in oil paintings or cyanotype. “After painting them, I was like, what is the connection between all these things? And why am I interested in it?” Ouyang said.

Ouyang began oil painting in 8th grade, they said, adding that they paused working in the medium for a while before restarting in the past year. “I really enjoy using that medium (now),” said Ouyang.

Although Ouyang used to be drawn to figurative artists who explicitly convey queerness or Asian American identity in artworks, they are “straying away from that subject” now, they said, adding that artworks that expose the queer body may sometimes feel invasive.

“Now I’m kind of tackling queerness in a very different way where it is not explicit, but is definitely there in all of my paintings,” Ouyang said. “I’m so queer all the time that I think it’s definitely imbued into everything I do.”

Ouyang mentioned that coming into college, they took a step back from painting people, and specifically themselves, as they were “contending with (their) body and (their) gender and sexuality.”

But recently, they are returning to painting themselves — just never the head. “I didn’t feel like there ever was a need to paint my face,” Ouyang said.

For Ouyang, art is “magical and transcendental in that it’s like … expressing yourself and not even knowing you’re doing it.” They would start painting with a vision in their head — only knowing the reasons behind it until they push through “the ugly phases” of working and process its meaning.

“Art has really been helping me explore my own queerness and my own identity,” Ouyang said. “The people who have supported me the most in my art processes have been these chosen families I found in college.”

Ouyang added that moving forward, they hope to paint more in their own art style and deconstruct what they were taught in high school, on top of working through more photography and “archival photo processes” like cyanotypes.

“I’m interested in … contending (with) what it means to be from Georgia as a queer Asian American and what kind of queer and Asian communities that already exist here that I want to be more engaged with,” they said.

Read more from The Herald's Pride 2023 Special Issue.

Kathy Wang was the senior editor of community of The Brown Daily Herald's 134th Editorial Board. She previously covered student government and international student life as a University News editor. When she's not at The Herald, you can find her watching cooking videos or writing creative nonfiction.