A recent study co-authored by James Head, professor emeritus of geological sciences and professor of earth, environmental and planetary sciences, investigates why Venus is so different from Earth — despite the two planets’s physical similarities — and the implications for Earth’s future. The study, published in March, was a collaboration alongside researchers from the Southwest Research Institute, the University of California at Santa Cruz and the University of California at Riverside.

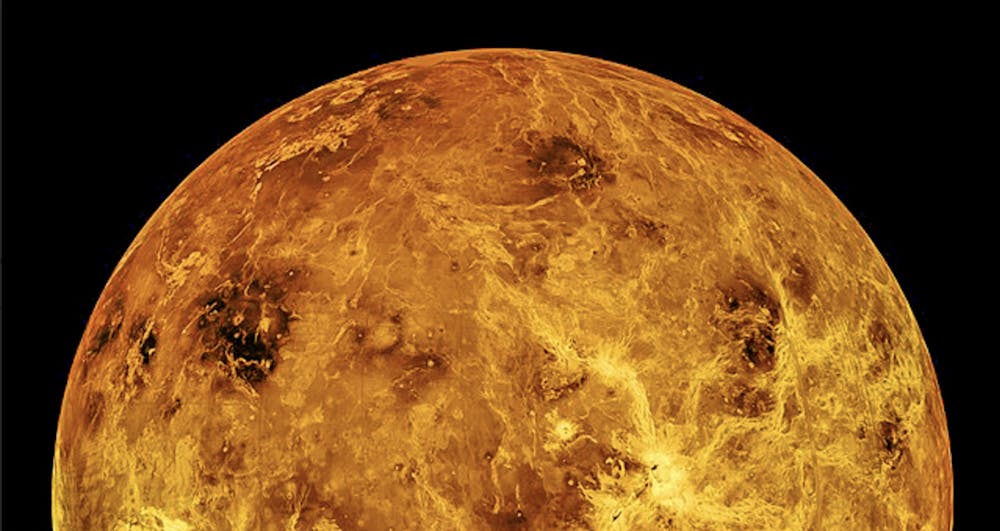

No other planet in the solar system shares as many similarities to Earth as Venus in terms of size and structure. Modeling the history of Venus could provide insight as to why the planets became so different — surface temperatures on Venus reach 900 degrees Fahrenheit, and sulfuric acid fills the atmosphere, according to NASA.

“The question is, how does something so similar have such a different atmosphere? And what are the causes of that?” Head said. “It’s not clear how long the Venus atmosphere has been there. We only have about 20% of the geological record.”

By looking to answer these questions, researchers aim to learn more about planet habitability and planet evolution. Data can further reveal information about the criteria needed for life to survive.

The study uses data from the NASA Exoplanet Archive, a compilation of data from observatories around the world. In the study, researchers identified over 300 Venus-like exoplanets, or planets outside the solar system.

“Venus is the most similar planet to Earth in the solar system. And we don’t really fully understand why Venus is so different from Earth, even though they are so physically similar,” said Colby Ostberg, a fifth-year PhD student at UC Riverside and head researcher of the study. “Observing exoplanets is a pathway to understanding what happened to Venus. We observe planets that have similar energy received from their star compared to Venus.”

“Planets like Venus are a real warning to us,” said Stephen Kane, professor of planetary astrophysics at UC Riverside, adding that understanding planets like Venus can reveal how planets can evolve — “how you get a habitable planet rather than a hostile planet.”

The criteria to select the 300 planets was based on planetary size, energy from a nearby star and the temperature level of that star. These planets were said to lie in the “Venus Zone,” which describes planets too hot to have surface liquid, but not so hot that the atmosphere is completely stripped away.

“The Venus Zone is the region around a star where a terrestrial planet will likely have an atmosphere pushed into a ‘post-runaway greenhouse state,’” Kane explained. In the post-runaway greenhouse state, excessive carbon dioxide in the atmosphere traps heat, causing surface liquids to boil away.

“For Venus, we see a very thick carbon dioxide-dominated atmosphere,” Kane added.

The list of Venus Zone exoplanets was then narrowed down to five most closely resembling Venus, according to the study. The five exoplanets will be observed by the James Webb Space Telescope, the largest optical telescope in space, and examined by researchers at the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York.

With data on the identified planets, NASA GISS could run 3D climate models on the planets, according to Kane. Those models could help researchers model the planetary history of Venus — and even explain what transpired to make Venus so uninhabitable.

According to Michael Way, physical scientist at NASA GISS, he and others are working with a complex digital program capable of modeling the atmosphere, land surface and ocean of planets. “It’s all coupled together in like three million lines of code, and it runs on the biggest supercomputers we have at NASA,” he said.

“We take that model and we can use it to model ancient Venus or ancient Mars, and the atmospheres of the planets. They will tell us what the atmosphere is made out of,” Way explained. “And then we can do detailed modeling to see whether that atmosphere could support a liquid ocean or not, for example.”

“That’s very important for the search for life, and also important for understanding the potential future of Earth,” Kane said.