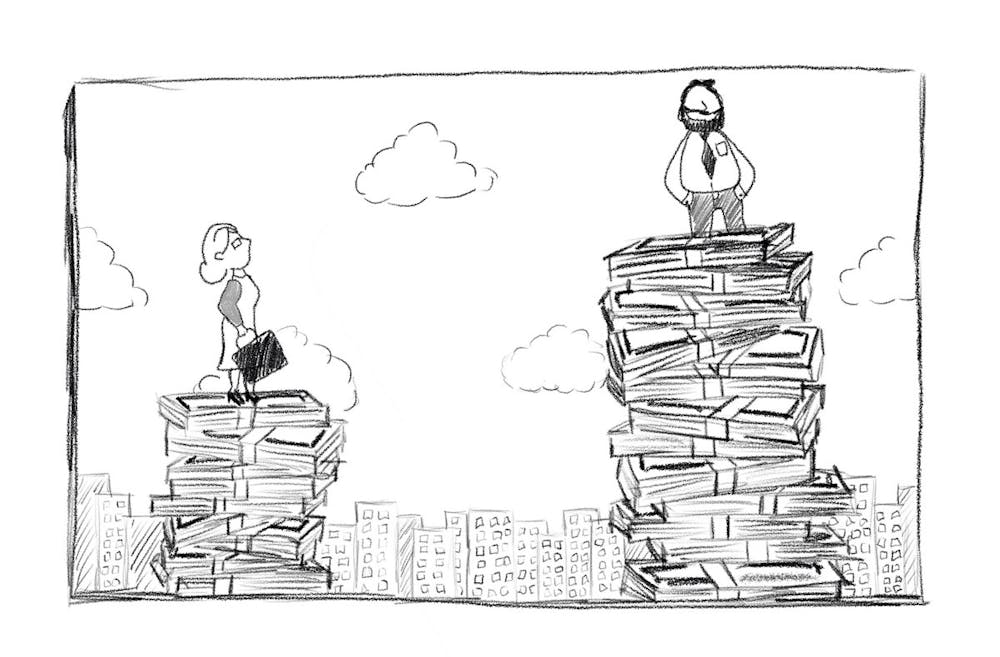

The gender pay gap between men and women in the United States has barely changed in the last 20 years. According to a recent study from the Pew Research Center, American women earned an average of 82% of what men earned in 2022.

The gender pay gap also varies across women of different races. Black women earn 70% of white men’s earnings and Hispanic women earn 65 percent, while Asian women are closer to parity at 93%.

The Herald talked to five professors to understand the implications behind this data.

While there are multiple factors that affect the wage gap, the largest reasons are having children — also known the “child penalty” — and the gendered division of labor, according to several University professors.

Current research shows that the gender wage gap starts to emerge after the birth of a woman’s first child, according to Anna Aizer, professor of economics.

“After children, you see women either reducing their hours, leaving the labor force or moving into occupations and industries that are more ‘child friendly,’” Aizer wrote in an email to The Herald. As a result, women trade earnings for more flexibility through “better hours, less travel (and) no weekend work,” she added.

Examining the gendered division of labor can explain the drop in earnings, said Senior Lecturer in Economics Kellie Forrester.

“If you think about a married man and a married woman, they each have their 24 hours in a day to divide between doing fun things … things around the household … and then working in the market,” Forrester said.

Research shows that women are more likely to take on household and childcare responsibilities, while men spend more hours in the market, according to Forrester. “Most of the gender wage gap now exists because of this division of time between the household and the market,” she explained.

There is not necessarily a linear relationship between hours and earnings, as firms often pay higher wages for working longer hours, Forrester added.

This makes for a decline in “the ratio of female earnings to male earnings” during the first decade of a woman’s working life, Forrester said.

Increased compensation for working longer hours also explains why the gender wage gap is larger in certain occupations. For instance, in business or law, firms offer greater compensation to people who can work outside of business hours and on weekends, according to Forrester. Women with childcare responsibilities who are unable to work such hours are paid significantly less.

The child penalty also accounts for a “large share of the variation in gender income gaps across places,” Professor of Economics and International and Public Affairs and Chair of the Economics Department John Friedman wrote in an email to The Herald.

Causes of the gender wage gap have changed over time. “Historically, there have been differences in educational attainment by gender and that played a role in explaining the gap,” Aizer wrote. “But that is no longer the case as more women are graduating from college than men.”

The disparities in education and experiences between men and women have shrunk significantly over the last 50 years, according to Forrester, while technological improvements have made completing household tasks a more efficient process. Better maternal healthcare resources and advanced contraceptives have allowed women to delay pregnancy or have fewer children, Forrester said. These factors have narrowed the gap by allowing more women to pursue education and enter the labor market outside of the domestic realm.

Still, the time flexibility required for childcare can limit a woman’s ability to increase her earnings, according to Assistant Professor of Economics Lorenzo Lagos.

“It’s hard to get rid of it because (the systemic aspect) is something that is very pervasive,” he said. Workplace structure, social norms around interactions and harassment in the workplace provide additional barriers to the gap’s convergence, Lagos added.

Disparities in the gender gap between women of different races have additional contributing factors, wrote Professor of American History Robert Self in an email to The Herald.

The gap has historical roots in “the legacies of slavery and Jim Crow, which explains why Black women’s labor is undervalued,” Self wrote. Additionally, the gap is impacted by the “‘dual labor market’ that developed in the 19th century, in which white labor was priced at one level and the labor of people of color” at a lower one, he added.

Professors generally did not expect the gap to narrow anytime soon, although several offered ways to address it. It “has not closed recently, so it’s not clear that it will in the future,” Aizer wrote. “Remote work might help — though it's not clear — and of course more funding for child care would also likely help, as well as greater flexibility in work schedules.”

According to Forrester, men taking on more childcare responsibilities could help close the gap. To encourage this, firms would have to accommodate flexible hours by restructuring business relationships and resetting expectations for professional meeting hours, she explained.

While gender differences across occupations do not account for the largest part of the gap, “thinking more intentionally about how to encourage women to enter higher paying occupations” could also decrease the gap, Forrester added.

“I’d like to be hopeful, but I think it’s very hard to address the factors that are driving this.” Lagos said. He pointed to his research on labor unions in Brazil that prioritized female-centric policies in bargaining and were able to improve workplace conditions for women, suggesting that similar efforts could drive change in the US.

With regards to cultural shifts, “if young people are interested in these issues … then maybe some of these things will change,” Lagos concluded.