New York University President Andrew Hamilton visited Brown Thursday to give a lecture on a subject not a part of his usual topics of conversation as a university president: organic chemistry.

Hamilton discussed his over 40 years of research experience in a talk titled “Recognition at the Molecular Level” for the chemistry department’s annual John Howard Appleton Lecture. The event marked the 100th anniversary of the lecture program, according to Lai-Sheng Wang, professor of chemistry and department chair.

“Over the past 100 years, we have had world-renowned chemists and physicists as Appleton lecturers to share their knowledge and wisdom with us,” Wang said. He added that 15 Appleton lecturers have won Nobel Prizes.

Professor of Chemistry Paul Williard introduced Hamilton, noting his “remarkable career” as both a university president and chemist. Williard highlighted Hamilton's administrative skills and his body of research, which totals over 500 scientific publications.

Hamilton’s research operates “at the interface of organic and biological chemistry,” he wrote in an email to The Herald.

At Hamilton’s lab, “we use the techniques of organic synthesis and molecular design to create entirely artificial chemical compounds,” Hamilton wrote. The artificial compounds mimic nature and possess properties associated with DNA and proteins.

Studying these compounds provides insights into “complex biological processes” such as recognition and catalysis in addition to potentially helping researchers “interfere with (abnormal) cellular behavior that occurs in diseases such as cancer and Alzheimer's disease,” he wrote.

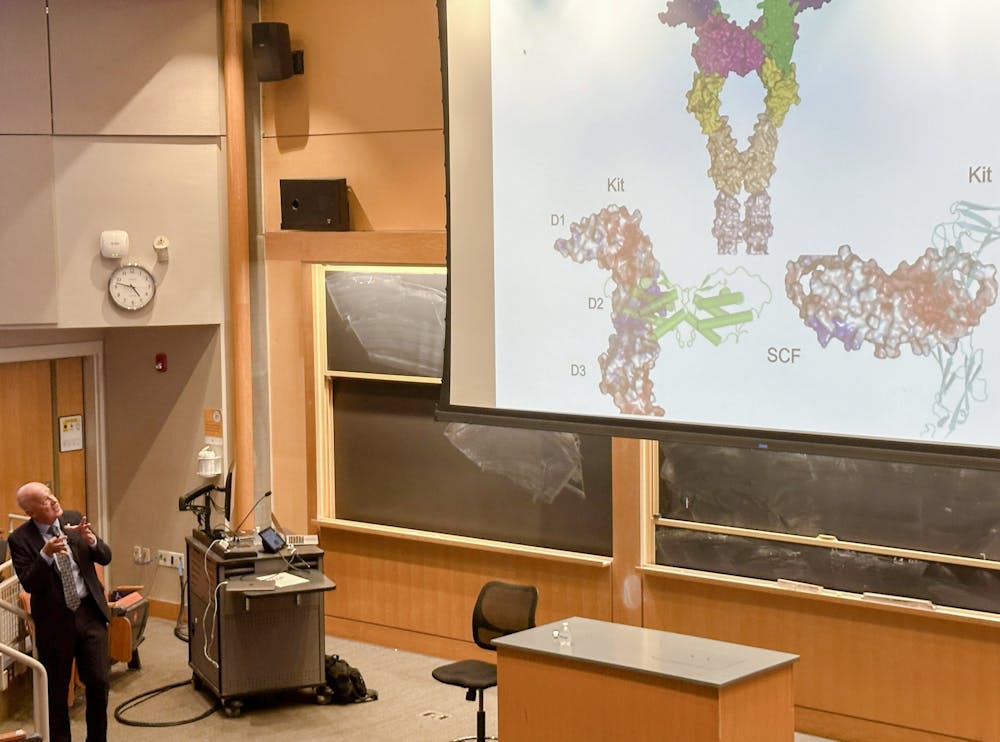

During the lecture, Hamilton discussed the evolution of his research over the last 40 years, specifically noting “the role that chemistry can play in controlling biological processes” through selective recognition — a process in which a compound binds with a complementary counterpart through a series of interactions.

Hamilton said that the artificial compounds he worked on throughout his career exemplify how “molecular design and synthesis can be used both to modulate recognition and … control the behavior of” proteins.

Hamilton reflected on early research from his group that demonstrated the importance of non-covalent interactions in molecular recognition. In subsequent years, the group simplified these early models and applied them to the study of organic solvents.

Over time, Hamilton and his team were able to study the chemistry of recognition in systems that more closely resembled cellular conditions, allowing for biological applications. In addition, the molecules that he synthesized became increasingly more complex.

Toward the end of the talk, Hamilton touched on a medically-relevant class of proteins known as intrinsically disordered proteins. These proteins have no stable structure and are associated with human diseases such as Alzheimer’s, he said.

Hamilton’s team was able to utilize principles of molecular recognition to block the process of amyloid formation, which can cause cellular damage.

Hamilton will speak to students and faculty again at the departmental Chemistry Colloquium with a lecture on Friday entitled “Synthetic Mimics of Protein Structure and Function.”

Ryan Doherty is the managing editor of digital content and vice president of The Herald's 135th editorial board. He is a junior from Carmel, NY who is concentrating in chemistry and economics. He previously served as a university news and science & research editor, covering faculty and higher education.