Tears, laughter, and joy spill across the strings of Taylor Swift’s guitar. This is the Taylor I know and love. She is the one who always listens, the one who got me through middle school, the one who makes me jump and shout with glee—all with a mere click on Spotify. This Taylor disappeared with the release of Reputation, but her later album, Lover, is more complex: It lingers in the liminal, then bounces continually from majestic to awful and back again. Lover has moments of breathtaking beauty, sadness, triumph, and then some embarrassingly bad songs. After listening to the album for the first time, I could not decide how I felt about it. My indecision was not the passive kind that marinates in the back of your brain while you go swimming and eat watermelon in the summer sun; instead, it was the kind that followed me everywhere, the pros and cons frustrating me at every step. I simply could not come to a conclusion. Finally, I decided the only way to get it out of my head was to write about it: This piece is the story of my confusion, and what it might reveal about the way we see our greatest stars.

The beginning of Lover left me craving something to rid my mouth of the bitter taste of disappointment. The old Taylor is strangled by electronic beats and an overly-enthusiastic drum kit. “I Forgot that You Existed,” the album’s first track, sets the tone with robotic pounds and claps that swallow her voice. There is no narrative; her distinctive tenderness and depth disappear into a chasm of empty “oooh’s” and “aaah’s.” This is nothing compared to “ME!”, in which Taylor takes her cringe-inducing high register to a new level that is neither catchy nor substantive. The only sound available to mask her vocal wandering is an aggressive drum, pounding listeners’ ears into submission.

After “Cruel Summer” comes “Lover,” the title track. The opening chord made my heart soar, and I was hopeful once more for the Taylor who had been so therapeutic to me in the past. The song begins with the line, “We could leave the Christmas lights up 'til January / This is our place, we make the rules.” Suddenly, I jumped to my feet, clinging to the remnants of the old Taylor Swift resonating through the line. From the outset, she establishes a clear and unique setting, a throughline present in all her greatest hits. The lyric mirrors lines that have been burned into my mind through years of lip syncing into the foggy bathroom mirror; lines like, “There's somethin' bout the way / The street looks when it's just rained / There's a glow off the pavement,” from the first song on her second album, Fearless. In “Lover,” her guitar resurfaces on the track as well as in the imagery. She sings, “Ladies and gentlemen, will you please stand? / With every guitar string scar on my hand,” an acknowledgment of the history and the power of her guitar. The next song, “The Man,” shines a light on Taylor’s dark side, thrusting the parts of her I have tried to avoid—in order to remain an unquestioning superfan—into the open: the shortcomings of her politics. I have no qualms with the message of the song (in “The Man,” she sings about the double standards between men and women) but I do protest the way in which she expresses these messages. Instead of singing about raw emotional pain, she shies away from reality and uses lines that are catchy and convenient. There is no vulnerability in the lines, “What's it like to brag about raking in dollars / And getting bitches and models? / And it's all good if you're bad / And it's okay if you're mad.” Here, her feminist critique is imagining a world in which women can say “bitches,” and be bad. The commentary itself is certainly invaluable. However, the lyrics are nonetheless shallow because they stop there. For an artist known for baring her innermost pain and emotion to the world, her political lyrics are confoundingly hollow.

Taylor also has a history of stealing from other cultures when it is convenient to her career—including a soft impression of Beychella’s radical Black aesthetics at the Billboard Music Awards in 2019—and unfortunately, Lover is no exception. For example, “You Need to Calm Down” is a more contemporary example of her habit of appropriating another culture without interrogating her relationship to it. As one of her few political songs other than “The Man,” this song and its performance is another example of Swift trying to address her lack of political action. “You Need to Calm Down,” a song released during Pride Month, implicitly compares Taylor’s own experience with Twitter trolls to the struggles of victims of transphobia and homophobia. In the first verse, she sings, “Say it in the street, that's a knock-out / But you say it in a Tweet, that's a cop-out / And I'm just like, ‘Hey, are you okay?’” Swifties who have been following her music and career for years are familiar with her struggle with Twitter trolls; however, in the next verse, she suddenly jumps to hate speech, framing it as another iteration of “trolling”: “Sunshine on the street at the parade / But you would rather be in the dark age / Just makin' that sign must've taken all night.” Without her typical Swiftian narrative arc, the first verse and the second verse simply stand next to each other. There is no empathetic journey to follow as a listener; instead, we are left with a simple false equivalence.

The music video for “You Need to Calm Down” illustrates this fallacy through her connection to the LGBTQ+ community as an ally in a narrative and complex way. The video features Taylor walking down a road arm in arm with LGBTQ+ identifying celebrities while singing using the pronoun “we.” In the climax of the video, she brings the focus back to Twitter trolls and online beef. Taylor has been engaged in a notorious feud with Katy Perry for years. At the end of the music video, Taylor and Katy share a passionate embrace (Katy wearing a hamburger costume and Taylor wearing a french fry costume). The embrace rings true with what we already know about Taylor Swift: that she loves tying her narratives up with a bow. However, once again there is no arc: there is only juxtaposition of things with no clear relationship—from food costumes to Twitter to LGBTQ+ activists.

For Lover to be an ambiguous album, Taylor had to follow “You Need to Calm Down” with something huge: an epiphany of sorts. “The Archer” is exactly what I was waiting for; it is a piece of intensive introspection that digs deeper than Twitter. In the chorus, Taylor sings, “I’ve been the archer/I’ve been the prey.” This song is a hauntingly beautiful expression of a basic concept: hurt people hurt people. This recognition is a step towards a Taylor who can sing about heartbreak and hatred and also about the pain she may inflict on others, pain she is not a victim of. “The Archer” narrates a journey towards self-awareness while soaring through chilling melodies. This is the Taylor I love: the one who blends pain, sorrow, and healing into musical magic and story.

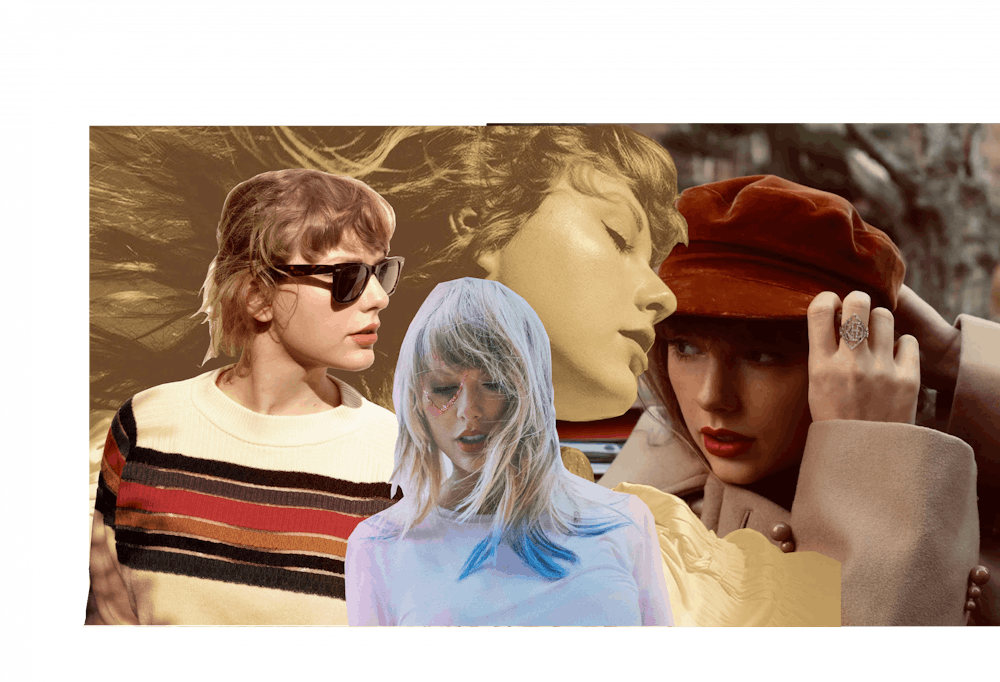

If “The Archer” is Swift’s epiphany song, her reckoning with heroes and villains not being binary categories but a dialectic we are always moving between, my listener and superfan epiphany came when I heard False God. The chorus ends with the lines, “Even if it's a false god / We'd still worship this love,” and as soon as I heard this, I realized the gravity of my error, and the reason why my indecision about Lover had tortured me so. People are never just “fans” of Taylor Swift. The “fans” I know would categorize themselves as “obsessed.” Obsession is a dangerous thing; it surpasses admiration and approaches worship. I had been worshiping Taylor since middle school, and in doing so I raised her to a level of divinity she could never reach. I doomed myself to perpetual disappointment by refusing to acknowledge her humanity. If she could recognize that her flaws and her successes are both integral parts of who she is in “The Archer,” why couldn’t I? Old Taylor is forever encapsulated in albums like Fearless and 1989; I can always go back and listen to them when I want to experience the beauty and complexity of old Taylor, for they are “timeless.” But, I refused to acknowledge that Taylor is human, and she is not an omniscient being designed to solve all my problems. As long as I pretend that she is, I am doing her a great disservice by denying her the space to err, move on, and grow, as all people must do.

Taylor loves happy endings: the music video for “You Belong With Me” ends with the narrator finding out her crush loves her too; “Love Story” ends with a triumphant verse in which “Romeo” proposes to “Juliette”; in “How You Get the Girl,” the final chorus changes from “how you get the girl” to “how you got the girl.” I hungered for that happy ending in Lover, and was left vexed when I discovered it was so much more complex than that. I still have not come to a conclusion about whether Lover is a “good” or “bad” album, but I have learned that I must not reduce Taylor’s narrative to what I want it to be; otherwise, I am just as guilty of dehumanization as she. When I lift her to the divine plane, I deny her the human experience that makes her an artist.