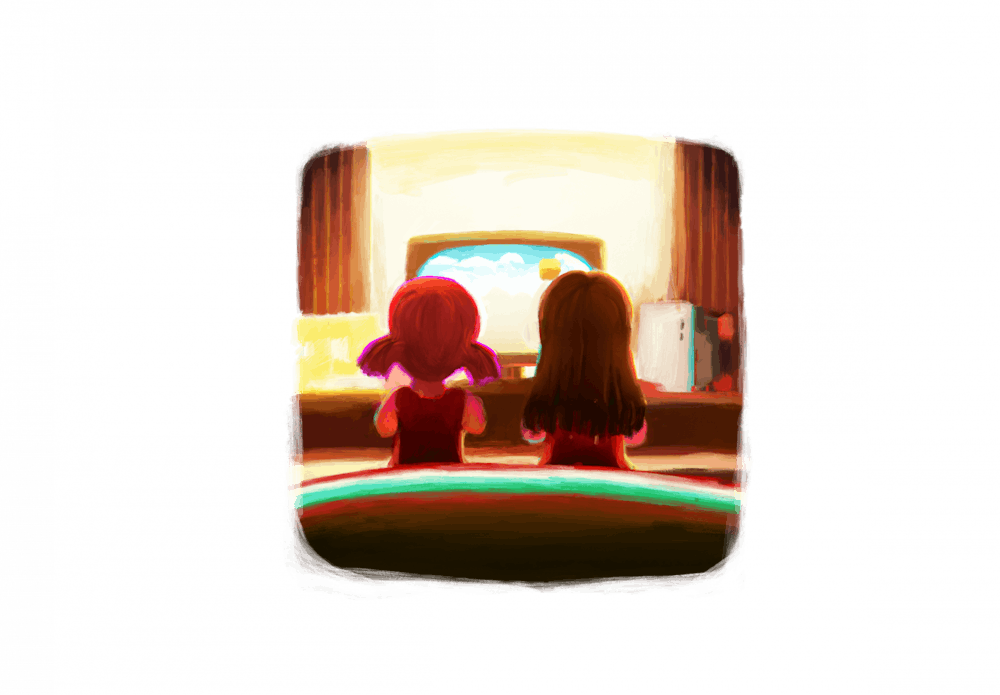

My childhood best friend Lilah once discovered a copy of Super Mario Bros. on the hallway floor of our middle school and stole it. Neither her conscience nor mine stopped us from taking it to her house after school and immediately plugging it into her pink Nintendo DS. For the next few months, every time I went over to Lilah's for a sleepover, we constructed an elaborate pillow fort on the floor of her room and huddled around her DS, taking turns playing Super Mario Bros. She taught me how to climb the walls without stairs by ninja jumping. I showed her a green warp pipe that I found underwater, which sent Mario into a secret realm full of gold coins and venus flytraps. When I ran out of lives, it was Lilah's turn; when she ran out of lives, it was mine. I started to develop a Pavlovian rush of excitement in response to that Mario death sound effect, because it meant it was finally my turn to play. We passed the DS back and forth until either we or the DS ran out of energy—whichever came first. On particularly treacherous stretches of terrain, we whisper-sang a spirited rendition of Dory's "Just Keep Swimming" from Finding Nemo, which was frequently cut short by the sound of her dad's footsteps pounding up the stairs as he rushed to reprimand us for being awake past our bedtime. Lilah would quickly stash the DS behind her pillow and we would pretend to sleep, squeezing each other's hands to keep from laughing.

Eventually, Lilah lost the charger to her DS, and our midnight adventures through Mario's pixelated kingdom came to an abrupt end. But we didn't mind, because we had found a game to take its place: Webkinz, a virtual world in which we could take care of pets that had real-life stuffed animal counterparts. On Webkinz, Lilah and I cultivated online families together, looking after our pets like they were our own children: We fed them fruits and vegetables, celebrated their birthdays, furnished their homes with toys and rocking horses, and dressed them in matching outfits. We each had bought the same golden retriever from Hallmark; I named mine Charlie and she named hers Sophie. After some thought, we realized that the only logical way to unify our disparate Webkinz families was for Charlie and Sophie to marry; that way, all of our other pets—her heart-covered frog, her turtle, Michael, and my red robin, Alex—could be half-siblings, with Sophie and Charlie as loving parents. So, on the day of their union, we logged into the website and positioned Sophie and Charlie so that they were both standing in Lilah's Webkinz backyard under an animated white trellis and assembled our other pets around them. Simultaneously, in the real world, we held a ceremony on the floor of my parents' bedroom, in which we lined all of our Webkinz stuffed animals in rows, Charlie and Sophie positioned at the front of the room. Once the two animals had said their heartfelt vows and their union was sealed, Lilah and I held an hour-long Miley Cyrus dance party—partly to end the wedding but mostly to celebrate the fact that, now that our videogame children were married, we were technically sisters.

Every day after Lilah's mom picked us up from school, we ran straight to the desktop computer in her dad's office to play Webkinz. She sat in his big black swivel chair and I perched on its arm, waiting eagerly for her to log into her account. Just as we had done when we played Super Mario Bros, we traded off game-for-game. It was like a choreographed dance; both of our eyes stayed glued on the screen, leaning forward, tongues poking out, then an exasperated sigh and we changed positions. But we never grew tired of playing this way. It was a familiar cadence, the rhythm that defined our friendship.

Because of my relationship with Lilah, I found comfort and familiarity in Gabrielle Zevin's novel Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow, which tells the story of Sadie and Sam, two friends who meet as children, grow apart, and then meet again in college, ultimately deciding to go into the game-designing business together. Zevin uses a story about video games to highlight more universal aspects of the human experience: the unpredictability of life and the intimacy of friendship.

Sadie and Sam meet for the first time at 11 years old in the kids' rec room of a hospital and bond over Super Mario Bros.—just like Lilah and me—and slowly open up to one another as they continue to play. Sam is recovering from a car accident which crushed his foot, and Sadie is in the hospital visiting her 13-year-old sister, who has cancer. When Sadie tells Sam she'll wait to play until his character is dead, she realizes that she may have come off as insensitive to Sam's condition. Sam, still playing, says, "This being the world, everyone's dying." He then hands her the controller: "Here. My thumbs are tired anyway." For these children, who each bear heavy burdens in their personal lives, it is easier to plunge into a virtual world, to immerse themselves in the rhythm of the gameplay, rather than express themselves explicitly. I found parallels to my own relationship with Lilah in Sadie's relationship to Sam. Particularly when we were young, it felt more natural to channel our social energy into an external task than to focus it on one another. We learned about each other through our unique styles of playing and choices rather than through conversation: Lilah could play the same game for hours without getting bored or giving up, and she found everything cute—monsters, animated sunflowers, Mario's exclamations ("Let's-a go!", "Mario number one!")—and she was always one to save her in-game currency, whereas I was always bordering on broke.

It's been 10 years since Lilah and I lay on the floor of her room with her DS, but we still play Super Mario Bros. on my older brother's Nintendo Switch when I see her once a year. Something about that unified focus on a task has a neutralizing effect, turning back the clock until we're back to chanting just keep swimming, as if we'll have to scramble to turn off the game as soon as we hear her dad's footsteps coming up the stairs. Zevin's story addresses the notion that friendships which begin in early childhood almost always drift apart—sometimes for a few years, sometimes for many. Sam and Sadie's childhood friendship ends at age 12 and then rekindles in college, when they decide to start making video games together. Their paths remain intertwined as they work as business and creative partners together until their thirties, when Sadie moves to Boston and Sam remains in Los Angeles. When Sadie and Sam finally see one another again after years apart—first in college and then later in middle adulthood—they are still able to connect with one another, slipping back into that back-and-forth rhythm of gameplay. Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow is a reminder that the routine and the invariability of gaming worlds can be a blissful escape from the real world, where relationships are messy and turbulent, where stories get cut short.

At the end of fourth grade, Lilah moved to Oklahoma. When she left, Lilah gave me her username and password to Webkinz, and when I missed her, I would log onto her account. Our friendship taught me that when you experience art with someone—whether it be a movie or a song or a video game—the memory of them is crystallized in it; the art becomes a way to access them. Sometimes, I knew she'd logged on recently too because I could see that the Wheel of Wow had been spun, the daily gem had been mined at the Curio Shop, and Vinny the heart-covered frog had recently been fed his favorite food (candied rose petals). In those moments, I could picture her, wild blond hair pushed behind a pink headband, eyes laser-focused on the screen in front of us. Momentarily, I found myself next to her again, waiting for her game to end so that we could switch places and I could play. There was something so comforting about the immortality of that online world. Even if you let your avatars go unfed for years, they never died. Their house was always just as you left it, your progress was saved, the graphics were never updated. It was a relief to return to a world where everything stays the same.