June 6, 2008 was the first time I saw an iPhone. I was sitting in a Jewish deli next to the hospital where my mother was in labor with my brother. At the time, I only knew the flip phones I saw in movies and the Blackberries my parents used, which solely piqued my interest when they let me borrow one to play Brick Breaker. But this new phone had everything. I marveled at its camera, an app I could click on with my finger, that opened and closed with a swirling motion. Instead of just Brick Breaker, you could put whatever games you wanted on it by downloading them from an “App Store.”

Gen Z is the first generation to grow up with smartphone technology at our fingertips; the technology grows with us. People born at the beginning of the millennium aren’t young enough to have been iPad babies, but by middle school, we were hooked on every app from Tiny Wings to Twitter. Big tech companies at that time were just beginning to discover how the interest they created could transform into addiction. This contemporary tech was new, so we experienced many glitches; we’re essentially a generation of guinea pigs.

I joined Snapchat in 2011, the year it was created, and Instagram soon after, without even having the term “social media” in my vocabulary. When I made an Instagram account on my iPod Touch at age 11, I didn’t have to ask for my parents’ permission—it was free on the App Store, and neither them nor I knew what it was. I heard it was a place to share photos with your friends–one photo at a time, in a square, with one of four filters applied to it. That was all the app was capable of doing.

As I grew up, I watched Instagram, Snapchat, and other similar applications and technologies fumble with new features and adapt into what they are today, nonchalantly signing over my data and my time for the promise of strengthened online friendships. The rapid expansion of these platforms was overwhelming to a growing teenager like myself, especially given that it was unclear which were fads and which would stay. Vine came and went, as did House Party (with a stunning resurgence during the beginning of the COVID lockdown). Facebook faded, Musical.ly became TikTok and caused a new boom, and though I no longer maintain Snapchat streaks, I still depend on Instagram, and many rely on Twitter.

I don’t have many physical copies of photos from my childhood or any “home videos” taken on real cameras, but I was born too soon for it all to be documented via iPhone. I was six when the first iPhone came out. Even by the time I got one seven years later, the technology was not advanced enough to store all your memories in iCloud without losing some every now and then. At the time that iCloud was introduced, no one really understood what it was or trusted it entirely. I became skeptical of its capabilities one day in middle school when my phone crashed randomly, and my backup external hard drive broke—I lost almost all of the photos from the past few years.

I matured in a strictly tangible sense, which is perhaps why I obsessively hold onto mementos like ticket stubs, postcards, and birthday notes, and why I refuse to purchase a Kindle and insist on only reading physical copies of books. Simultaneously, my virtual self-image was just beginning to develop. My parents documented my early childhood via digital cameras, but they rarely printed out any of the photos to store in physical photo albums, the way people of the previous generation did with film photography. Many of my unseen childhood memories lie on random SD cards strewn about my house, likely to not be uncovered any time soon. The “Glitch Generation” lies somewhere in between the film and digital ages—where the data stored on new fancy devices ran the risk of vanishing, yet was simultaneously available to broadcast widely and instantly.

What does that mean for memory, and what does that mean for art? My questions, posed amongst a group of my Glitch Generation friends, recall a concept explored by Walter Benjamin, a German Jewish philosopher and cultural critic, in his 1935 essay, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” Benjamin proposes that the mechanical reproduction of anything automatically devalues the aura of the objet d’art (a small, ornamental work of art). He believes that in the absence of any ritualistic and traditional value assigned to an object, “the authenticity of a thing is the essence of all that is transmissible from its beginning, ranging from its substantive duration to its testimony to the history which it has experienced.” His concept emerged during the Nazi regime, but his introduction of the aestheticization of politics (i.e. a spectacle that enables the masses to express themselves without affecting ownership relations) into our cultural vernacular transcends time.

Do digital art and memorabilia inherently hold less value in their auras than certain physical objects and mementos? To me, tangibility certainly enhances emotional value, regardless of an object’s monetary value. The essence of a handwritten note from my grandfather or a portrait my friend painted of me contain testimony, history, lived experience that a photo of neither item could ever replicate.

What would Benjamin make of a Snapchat, a photo, or video message that disappears permanently after it is opened, or Banksy’s infamous $1.4 million painting that shredded itself at a Sotheby’s auction in 2018 and later sold in 2021 for $24.5 million at another auction, despite its physical form being destroyed?

How about art created by our newest toy, artificial intelligence like DALL-E 2? Robots might be capable of creating art that looks like it could have been made by a talented human, but to what extent does any of it hold authentic value or cultural authority? Likely, Benjamin would argue it does not contain much meaning, because, as he states, even the mere existence of a copy of anything diminishes the value of the original. If anyone can conjure the same piece of digital art within seconds, the item no longer possesses the unique singularity that made it meaningful.

I would assert that a journal kept in the iPhone notes app would eventually hold less emotional value than one documented in a physical notebook in someone’s handwriting on a page they touched. A printed photograph taken on a film camera might hold more sentimental value than one on an Instagram feed that has been curated to present a specific, typically less than truthful self-image. There is a distance between who you present yourself to be and who you really are.

Glitch Generation kids have somewhat caught on to this; we’re experiencing a film revival that is meant to be nostalgic, even though we weren’t alive when it was first popular. Disposable cameras are used at parties, perhaps as an aesthetic trend, but also as a means to grasp something physical. A stuffed animal, a drawing, and an annotated copy of a favorite novel are all items that reflect a person’s true self. They cannot be FaceTuned or filtered, and even if you lose them, they will never truly vanish.

I often wonder if Instagram will last forever or if it’s just an elongated fad. I can’t imagine my children one day scrolling through my hundreds of posts to see what my online persona was like when I was their age, but perhaps that is the destiny of our digital footprints.

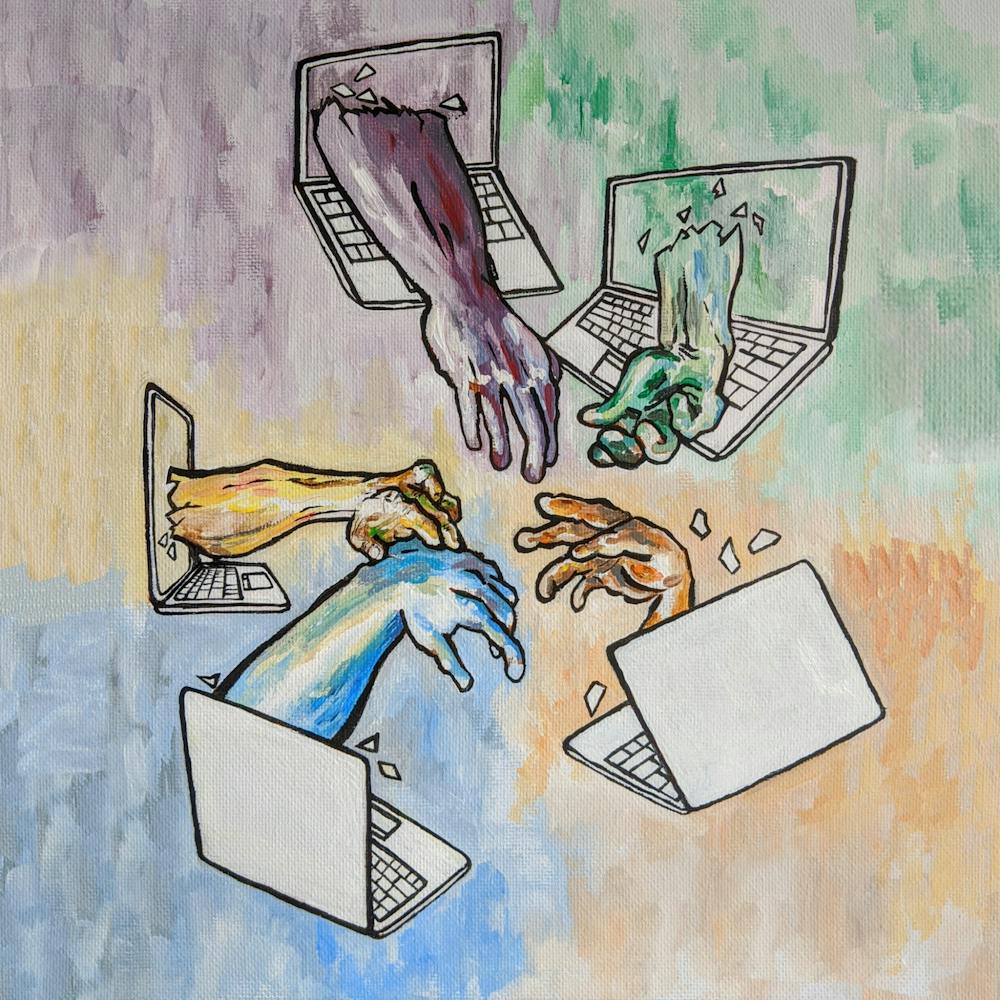

Given that we continue to experience myriad glitches as society rapidly invents and adapts, there is no way of knowing whether any tech is permanent. Conceivably one day soon it will all disappear before we can print any of it for a photo album; people still sometimes get permanently locked out of their Instagram accounts and must start over. Being born into the Glitch Generation is exciting and creates an instant convenience my parents didn’t have, but gone is the ephemerality and the emotion. We’re all just searching for something to grasp.