Dear Pastor B,

Of you I remember almost nothing. I remember a speech about divine grace you gave before we watched Kung Fu Panda at Bible camp. I remember your spindly fingers and the bumpy blue-gray veins that pulsed down your forearms, and the way you walked with a thumping arrhythmic gait. I remember the call-and-response you used to get us to quiet down: You sang out bum bum buh-dum bum and waited for us to sing back bum bum! I remember your white hair and your hawkish blue eyes. I remember how odd I found it that you—a white man—were the one preaching to a congregation of Chinese children.

The rest of you is captured only in the haziest impressions. I can hardly recall a thing you told me about God. These shattered mirror memories are all I have left of you. Half of my life was spent going to Bible camp and Sunday school but I confess to no longer being Christian. I’m not sure that I ever was.

I write this not as an apology, because I have nothing to apologize for. I write this not as a means to reach you, because I know how unlikely it is that you will ever read this. I write this for myself, and perhaps for my mother, who still quietly worries about the status of my immoral, and unfortunately atheist, soul.

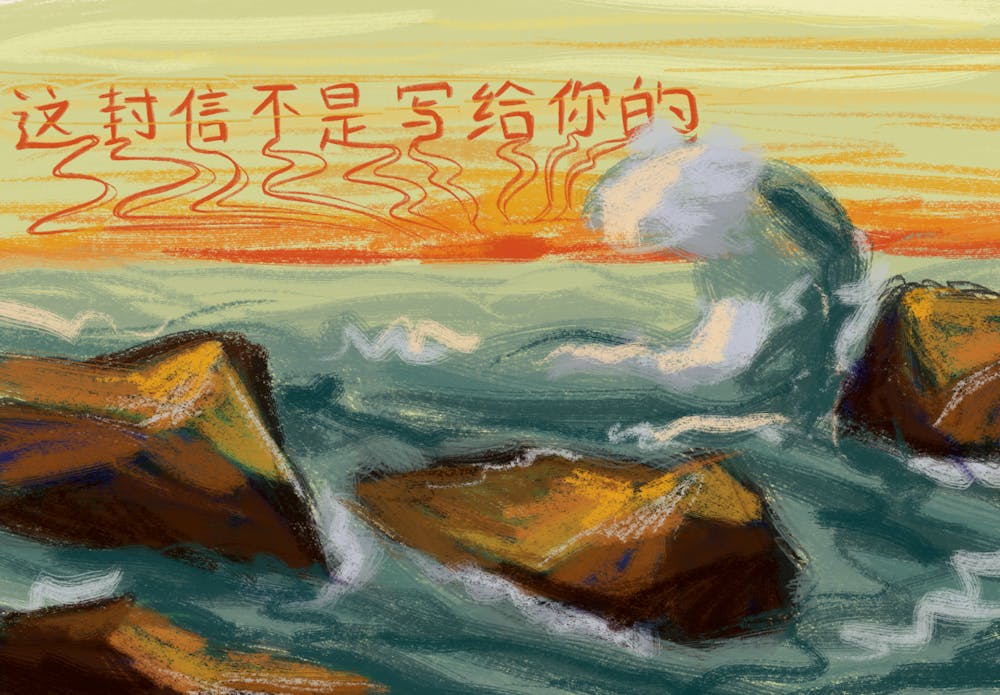

This is not for you.

I remember your wife, Angie, who held me when I cried during Bible camp activities. Do you remember that summer? I suspect you don’t remember it like I do.

In those years, summer came as a thunderstorm. There was not an hour of silence in our months. The cry of the cicadas was upon us during the days; at night it was the drum-beat rumble of thunder.

Before we were born, my mother and all the Chinese mothers in our town found God, and wanted their children to find Him too. This is why the Chinese church in my town doubled as the Chinese school. We learned about God on Sunday mornings, and we practiced our Mandarin on Sunday afternoons.

One mother in my neighborhood distributed pocket Bibles along with Skittles each Halloween. My own mother was never that overtly religious, but she sent me to Bible camp during the summers, just like the other Chinese mothers. For us, the humid summers acquired a divine texture.

At Chinese Bible camp, we learned about Christ through imitation. Do you remember the snack activities? You would stop by our classroom and teach us about a particular episode in the Bible, and we would construct the scene using food.

I remember you came over and complimented me on the Nativity scene I made out of pretzels and graham crackers—the infant Christ represented with a small marshmallow. A few minutes earlier, I’d stolen a handful of Jesus-marshmallows from the bag and furtively stuffed them in my pocket to eat later. I was too worried about you seeing them to properly listen.

I want you to remember the day I cried in the belly of the whale. One of our activities involved acting out Biblical stories. There was a large room in the basement of the church that we would go to for our reenactments.

This was on the day we were reenacting the miracle of Jesus healing the leper. A counselor picked a few of us to act as the lepers. She put fluorescent orange stickers on our skin, marking us as diseased. We were sent off to a corner, exiled as those with leprosy once were.

Do you remember this? The day before, we’d acted out the story of Jonah and the Whale. Jonah is swallowed by a whale and remains in its belly for three days and three nights, praying all the while. The windows in the church basement were still covered with big blue tarps, the darkness simulating the inside of the whale’s belly.

The few of us huddled together, swaddled in the excess tarp which pooled on the ground, in the whale’s belly. One by one, we were called forward to be healed by you. You’d told us how terrible leprosy was, how those with leprosy would be exiled forever, how the illness had been incurable without the touch of Christ. But you weren’t Him. You were only a man, peeling orange stickers off our skin.

I sat in the corner in the dark, and I cried. I didn’t respond when my name was called. You came to me and peeled the stickers off my skin, shushing me and my tears. The leprosy wasn’t real, but I was born sick. Your wife, Angie, collected me in her arms and whispered to me, “It’s not real, it’s not real.”

I tell you this not to blame you. I tell you this because I have no words to describe how I felt other than to just tell you this story.

In our town, summer ends not with thunderstorms, nor with the flight of cicadas, but with the drip of Chinese children returning home from Bible camp.

The Chinese church stood in a zone of perpetual construction. A mountain of earth always stood defiantly in the lot across the street. A dirty yellow bulldozer was always parked next to it.

A few years ago, an apartment complex rose where the mountain used to be. The church itself was renovated, now with a shiny white facade and large windows along the sides. Two new wings now jut out from either side of the church. I can no longer picture the inside of the building. Everything is unfamiliar now.

I have one more thing to say to you.

You preached to us in English. I remember how you told us about the Exodus—Moses leading his people out from Egypt. You asked us to think about what it would mean to live in a place that mistreats us, what it would mean to leave that place, to pack up our lives and cross seas. You asked us this not knowing that we have already been asking ourselves this question since we were born.

What do you know of Exodus? Or rather: What do you know of our exodus? What do you know of being untethered as we are, of being too Chinese for this country but being too American for home? You taught us about the Promised Land, but there is no such concept for us. We are only ever at home in liminal, impermanent places: doorways, school buses, the washed out places where the ocean meets the land, and in the Chinese school-church, where we spent mornings learning the language of God and afternoons learning the language of home.

I realize this sounds accusatory. I try to tell myself that you spoke only in good faith.

You told us that we were all God’s children—that I, too, was a wayward son to be saved. I’ve been thinking about that. I’ve been thinking about what would happen if I had a wayward son of my own.

Should I have a son, I would name him in Chinese after some consultation with my parents. I would name my son the same way that my parents named me: first in Chinese, but also English, with two names.

I would look at my son and tell him that no matter how many generations we stay in this country, we will always be foreigners; we will always be aliens in America. I would not insist that my son go to church or to Bible camp, but I would tell him the truth about this particular “promised land." And I would probably insist he go to Chinese school.

I will look at my son and tell him that this country is a cauldron: bubbling, bubbling, bubbling until our skin is split and our blood is boiled and our bones become the base of the broth that feeds a community.

Because only then, looking at my firstborn son, will I realize why my parents named me in Chinese. Because my parents, my son’s grandparents, left their whole lives behind them to come to this country. I’ll tell my son that every mile his grandparents traveled, they shed more of their skin, sanded down more of their corners, became so small in the soul that they could carry it all in a suitcase, taking with them only their language.

One more time: This is not for you. This is for me. And perhaps my mother.

Yours,

旦一

(Daniel)