Over the past sixty years, affirmative action and race-conscious college admissions have been the subject of extensive debate across the country — especially on university campuses.

For proponents, the practice is crucial for building a diverse student body. Opponents claim it offers few benefits and overlooks other measures of diversity not encompassed in race.

By this June, the Supreme Court will likely issue a ruling on the future of race-conscious admissions in two cases brought against Harvard and the University of North Carolina by Students for Fair Admissions.

But the recent challenges are not novel: Including the Harvard and University of North Carolina cases, race-conscious admissions have faced scrutiny in over half a dozen Supreme Court lawsuits since the late 1970s. And since the 1960s, Brown community members have demonstrated longstanding support for race-conscious admissions, with administrators contributing to amicus briefs and students demanding change from the University while voicing their opinions in op-eds published in The Herald.

The Herald compiled a timeline of student engagement with affirmative action, using witness testimony, Herald news articles and opinions submissions and interviews with expert historians.

1960s: ‘We will leave the campus until Brown University commits itself to our demands’

The first nationwide initiative on affirmative action came in an executive order from President John F. Kennedy in 1961, which aimed to ensure “equal opportunity in employment” by the federal government. Over the next five years, institutions of higher education began to adapt the ideas from Kennedy’s executive order as “a form of recompense for shutting black people out of the economy and out of education,” said Stefan Bradley, professor of Black studies and history at Amherst College.

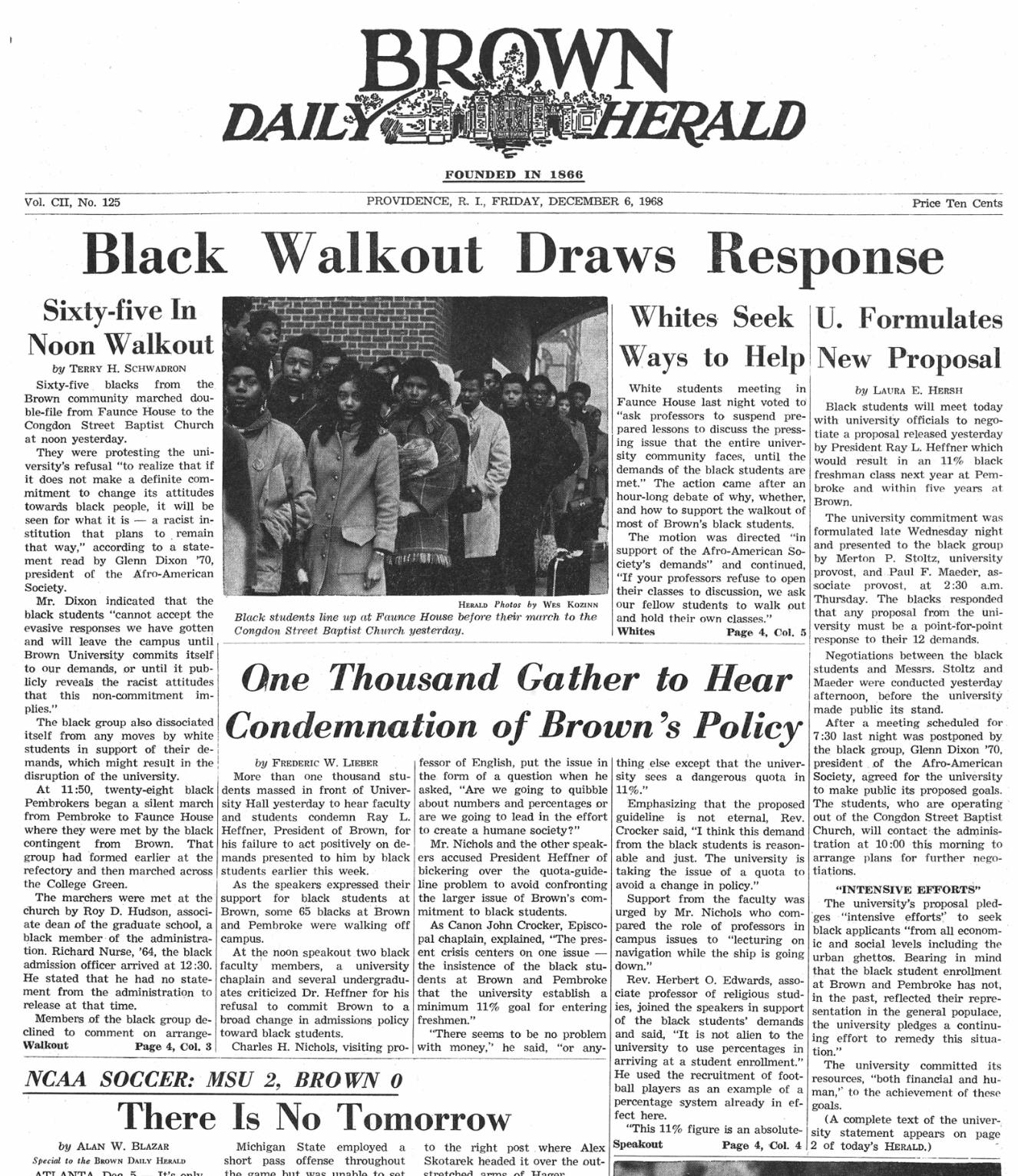

In December 1968, 65 Black students on Brown’s campus staged a walkout to protest the University’s lack of diversity in admissions, attracting more than 1,000 non-Black supporters, The Herald previously reported. With only 2.3% of Brown students at the time identifying as Black, community members demanded the University increase its Black student population to 11%, in order to reflect the demographics of the national population.

Glenn Dixon ’70, a leader of the movement, said at the time that Black students “cannot accept the evasive responses we have gotten and we will leave the campus until Brown University commits itself to our demands.”

After the students spent three days at Congdon Street Baptist Church following the walkout, the University pledged $1.2 million to recruit more Black students and work with the protestors towards reaching their proposed goals for the admission of Black students, The Herald reported at the time.

That night, 2,000 students signed a petition in support of the pro-affirmative action advocates — though representatives for the protestors said they were “in no way satisfied with these concessions,” which they called “racist in nature.”

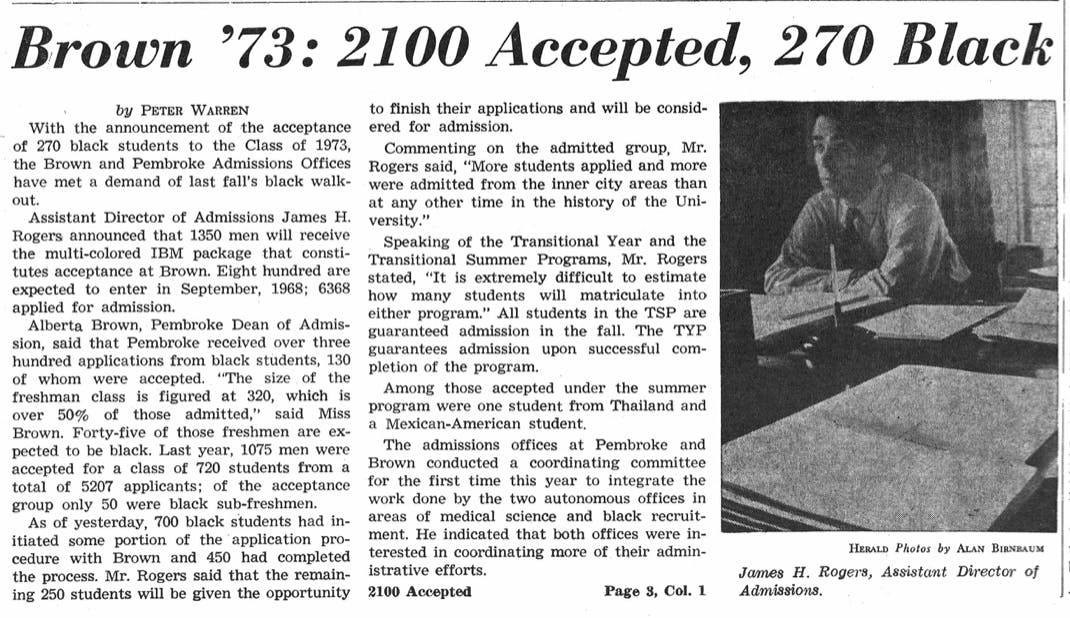

The University saw an increase of roughly 300% in applications from Black students in the following admissions cycle — 450 in total. When admissions decisions were released in the spring of 1969, 270 of the 2,100 accepted applicants were Black.

1970s: Affirmative action sees first major legal challenge

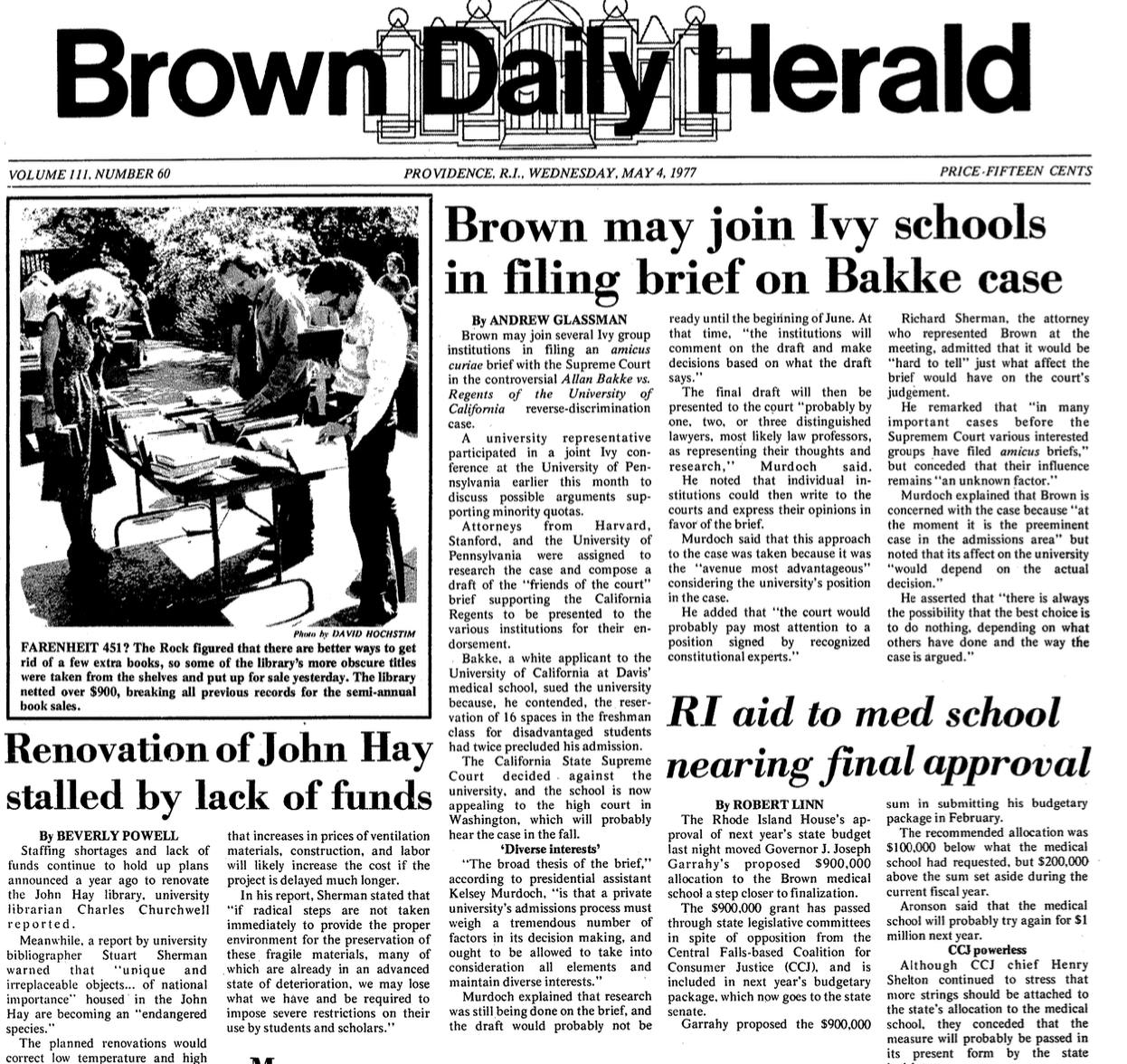

The 1970s saw the first significant challenges to race-conscious admissions in the justice system. In the Supreme Court case against the University of California at Davis, a white student, Allan Bakke, claimed that he was denied admission to Davis’ medical school on account of a racial quota.

In May 1977, a Brown representative attended a conference in which attorneys from various Ivy League schools discussed filing an amicus brief with the Supreme Court in support of maintaining a “minority quota” in college admissions. But Brown did not ultimately file an amicus brief in support of UC Davis.

On campuses, student engagement with affirmative action advocacy was “becoming increasingly popular,” Bradley said.

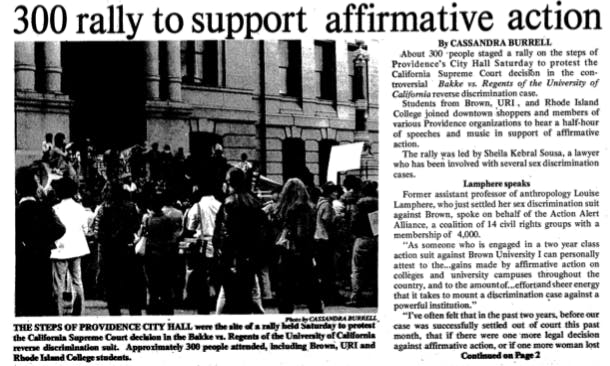

On Oct. 8, 1977, hundreds of students from Brown and local universities — including the University of Rhode Island and Rhode Island College — gathered outside of Providence City Hall to express their support for affirmative action, according to an Oct. 11, 1977 article by The Herald.

And one month before the Bakke decision in June 1978, David Egilman ’74 MD ’78 published an op-ed while serving on the medical school admissions committee discussing the lack of diversity in the medical school applicant pool.

“The average person on an admissions committee (was) looking for the platonic ideal of themselves — white,” Egilman said in an interview with The Herald.

“I was … making the arguments (for minority students) from inside the room,” he said. “But we would (often) lose.”

The Supreme Court partially sided with UC Davis in 1978, permitting race to be used as a factor in admissions, but also ruled that using quotas in the admission of minority students was unconstitutional.

Following the decision, Brown reassessed its practices to ensure that it was not using quotas in its admissions process, according to the Center at Brown for the Study of Slavery and Justice.

By 1989, 8% of the admitted class identified as Black, lower than the goal the University set 20 years earlier, according to Encyclopedia Brunoniana.

2000s, 2010s: From on-campus advocacy to legal support

In 2003, two cases brought against the University of Michigan — Gratz v. Bollinger and Grutter v. Bollinger — reached the Supreme Court, challenging Michigan’s race-conscious admission practices. Brown and 7 other Ivy-plus institutions joined Michigan in an amicus brief, supporting the use of race as a factor in admissions.

Such legal involvement signified a pivot for affirmative action advocacy. According to Bradley, in the early 2000s, “litigation became the way of protesting.”

“Rather than protesting on campus, (advocacy) went to court,” he said. While demonstrations on Brown’s campus had subsided, the University’s commitment transformed into legal action.

Following these two decisions, the court upheld affirmative action but substantially narrowed its scope — eliminating the use of points systems for admissions that used race as a factor alone, but allowing schools to consider race in a “narrowly tailored” manner.

In 2007, a Herald poll found that a majority of students — 53% — supported race-conscious admission practices. In a follow-up article, then Dean of Admission James Miller ’73 said that “in the admissions process, we’re looking at a dozen or more variables for each applicant. (Race) is not ever the sole factor.”

Around this time, two students — Jason Carr ’09 and Neil Vangala ’09 — founded “Asian Equality in Admissions,” a student group on campus that aimed to investigate Brown’s admission policies out of concern that they discriminated against Asian applicants.

The response to AEA was cold from 26 students — many of whom led affinity groups for Asian and Asian-American students — who signed an op-ed that spring. The AEA “did not form organically as a response to community concerns,” the op-ed claimed, adding that it came as “no surprise that it has not received support from any Asian or Asian-American student groups at Brown.”

In 2013 and 2016, Brown continued to legally advocate for affirmative action. In two cases against the University of Texas, one decided in 2013 and the other in 2016, Brown filed additional amicus briefs along with other top-ranked colleges to affirm its commitment to race-conscious admissions. The Court maintained its precedent of supporting race as a factor in admissions.

Today: ‘Not just sitting on our hands waiting for the decision to come down’

As it did for cases in the 2000s, the University has filed amicus briefs alongside other top colleges to express its support for affirmative action in both current cases. With the current court’s conservative lean, the future of affirmative action in college admissions is uncertain.

Several students told The Herald they believe affirmative action should be maintained to account for the institutional inequality present in the broader education system.

“There have been many centuries of oppression and marginalization of communities of color,” Willow Stewart ’26 said. “There is nothing equal about the system as a whole.”

“Everyone has the potential to be where they want to be,” said Dawood Olaniyi ’26, a QuestBridge scholar. “But that doesn’t mean that everyone is at the same starting point.”

But student concerns about a potential ruling against affirmative action have not spurred them into action. “I don’t think there’s anyone actually advocating as much as there is normal conversation about it,” said Cannon Caspar ’25.

Student opinions also may not necessarily line up with the opinions of the broader American public — 73% of which believes that colleges should not consider race in admissions, according to a Pew Research Center poll.

Stewart added that more students should go “on offense” in describing how they benefit from affirmative action — while noting that the policy is still the “least” colleges and universities could have done for Black students after centuries of discrimination.

Bradley added that institutions of higher education that “seriously believe in diversity” should also go “on offense.”

“If they truly believe in racial diversity, then put things in motion to increase diversity and increase the retention of these students,” he said.

The University is preparing for a decision overturning affirmative action, The Herald previously reported. Logan Powell, associate provost for enrollment, said in this month’s faculty meeting that Brown is “not just sitting on our hands waiting for the decision to come down. We’re doing anything and everything that we possibly can.”

This includes expanded outreach to applicants of color: The University plans to go on a recruitment trip with Howard University, a historically Black university, by visiting 15 cities in the south and southwest, according to the article.

Affirmative action, Bradley noted, “has benefited white students, faculty, staff and institutions much more than people of color.”

Those groups, he said, “get the opportunity to learn from people that they wouldn't normally learn from,” he added. “In that way, diversity has worked to benefit them the most.”

The Supreme Court is expected to rule on affirmative action in June 2023.

Owen Dahlkamp is the managing editor of newsroom on The Herald's 135th Editorial Board, overseeing the paper's news operations. Hailing from San Diego, CA, he is concentrating in Political Science and Cognitive Neuroscience with an interest in data analytics. In his free time, you can find him making spreadsheets at Coffee Exchange.