Leonard Jefferson was incarcerated in Rhode Island Maximum Security Prison for nearly two decades. From 1973 to 1985 and from 2014 to 2019, he experienced the state’s prison system from the inside, directly encountering problems ranging from staff misconduct to facility issues that put his health at risk.

The mold within the prison was so severe it gave Jefferson asthma and other respiratory difficulties — to the point where “just breathing the air” inside of maximum security was “torture,” he recalled in an interview with The Herald.

While J.R. Ventura, Rhode Island Department of Corrections chief of information and public relations officer, maintains that the operations and facilities of maximum security are safe and secure, many of the individuals living inside the prison tell a different story. On Aug. 22, individuals incarcerated in maximum security organized a hunger strike to protest their living conditions. Joseph Shepard, who took part in the strike, told The Herald that he estimated that over half of the maximum security population participated.

But RIDOC officials dispute that a strike occurred. “There have been no actions to indicate a hunger strike inside our facility, and no reports of inmates declaring to be on one,” Ventura wrote in an email to The Herald.

“Everyone here has either come out to eat or (has) chosen to stay in their rooms and eat the commissary food they have purchased to keep in their cells,” he added.

Activists and people incarcerated in maximum security told The Herald that the RIDOC’s failure to acknowledge the strike has made it harder to prompt change. As a result, the same adverse conditions within maximum security remain, making a future strike inevitable, according to Shepard.

‘The closest thing to hell on earth’: Life inside maximum security, demands for change

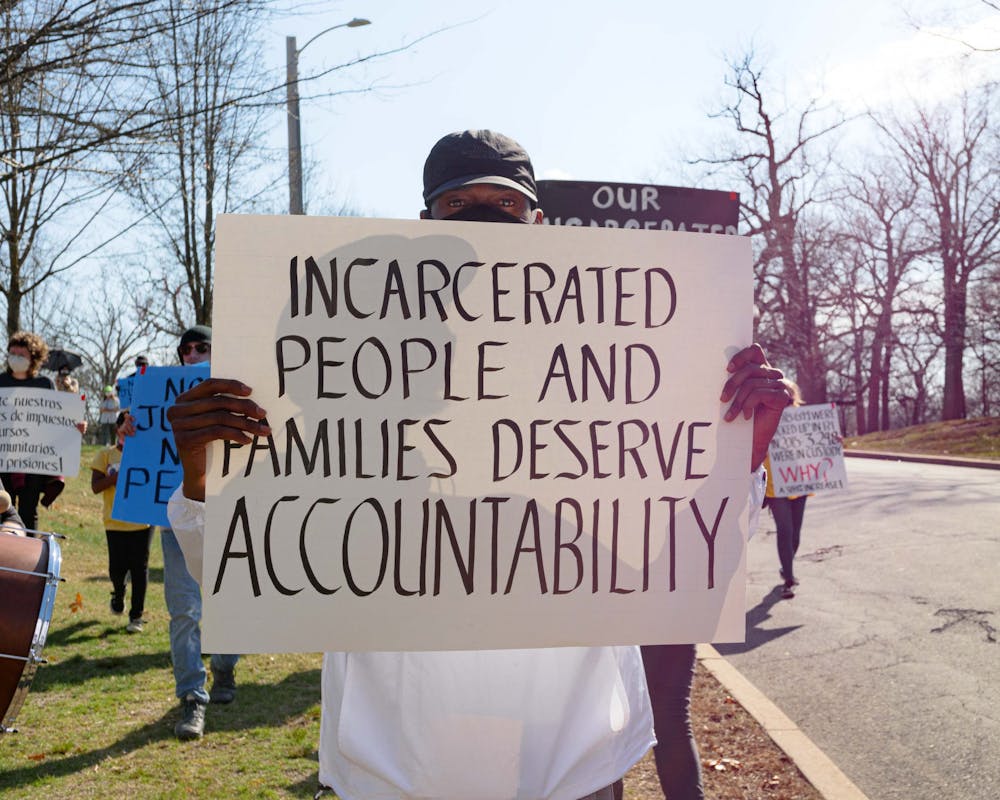

Strike participants demanded several changes to the conditions and operations of maximum security, according to Anush Alles, staff organizer at Direct Action for Rights and Equality, a Providence organization dedicated to organizing low-income families for social, economic and political justice. The incarcerated individuals who organized the strike reached out to DARE for external support, she added.

These demands included distributing fans to all incarcerated individuals in the prison, increasing recreational time to 8.5 hours per day, increasing wages for those who are incarcerated, expanding access to the facility’s educational building, creating a disciplinary process for incarcerated individuals in which they can present evidence and call witnesses when accused of misbehavior by officers, expanding vocational training programs and firing Captain Walter Duffy, who several inmates accused of hostility and misconduct, DARE told The Providence Journal.

Alles told The Herald that the strike was spurred by people in maximum security suffering due to a mid-August heatwave, which was exacerbated by inadequate access to air conditioning and ventilation issues within the prison.

Shepard participated at the start of the strike but was transferred to the John J. Moran Medium Security Facility eight days after it began, he told The Herald during a phone call interview from the medium security facility.

“The circumstances of (maximum security) are completely depressing,” he said. “You feel hopeless. You feel caved in. You feel like you’re already dead.”

Jefferson alleged that mold in his cell has led to ongoing respiratory health concerns throughout his time in maximum security. “My throat felt like it was filled with glue,” he said.

When inside maximum security, “you ask yourself if you have died already and (if) this is hell because this is the closest thing to hell on earth,” Shepard said.

Shepard also noted that low wages for work within maximum security exacerbate the effects of facility issues on incarcerated individuals who cannot afford the cost of living associated with accessing hygiene products, medication and outside visits to health facilities.

Ventura disputed criticisms of maximum security’s physical living conditions. Maximum security “is clean, safe and secure for everyone who is housed there as well as those who work inside,” he wrote. “The facility is exceptionally well run.”

But “the building is 144 years old. … It is not a very efficient building to run, and it is costing us more money in the long run than building a new, modern facility,” he added. “We absolutely need a new maximum-security facility in Rhode Island.”

While Jefferson explained that he was not incarcerated in maximum security during the heatwave and hunger strike, he and Alles wrote an Aug. 30 op-ed for the Providence Journal which called for the institution’s closure, spurred by the harm the heatwave inflicted upon incarcerated individuals.

Problems with prison personnel

Beyond facility concerns, activists who spoke with The Herald voiced concerns about the treatment of individuals incarcerated in maximum security by the prison’s staff. Shepard alleged that Duffy — a correctional officer captain at maximum security whose firing was demanded during the strike — at times took away individuals’ food and used degrading language toward them, referring to them as “rats.”

In response to allegations of mistreatment and the use of degrading language within maximum security, Ventura wrote that Max is “a safe, secure and constitutional agency.”

“While we are (a) prison and there are little luxuries here,” he added, “people housed inside our facilities are safe (and) treated humanely and in accordance with state and federal guidelines, as well as in full compliance with the Constitution of the United States.”

“Captain Duffy is a professional correctional officer with a great record of accomplishments and a distinguished career in public service,” he continued.

According to Shepard, “absolutely nothing” came from the strike except for increased hostility toward incarcerated individuals from those in power at maximum security. Combined with their living conditions, this can “make people who are trying to change their souls” feel “hopeless,” he said.

Shepard felt that correctional officers and public officials “don't want people to be rehabilitated or have an opportunity to never come back to prison,” because they profit off of the institution of mass incarceration.

In response to criticism surrounding the officers’ treatment of incarcerated individuals in maximum security, Ventura wrote that “correctional officers are authority figures and many people who have issues with authority, not surprisingly, end up in prison and say things that are not true.”

“As a matter of policy, any and all allegations against RIDOC employees are taken seriously and thoroughly investigated,” he added. “We hold ourselves to a higher standard and we have no tolerance for those who violate our Code of Professional Conduct or bring discredit to our profession.”

The future of maximum security prison in RI

Hunger strikes are sometimes referred to as “weapons of the weak,” according to David Skarbek, associate professor of political science. Because “incarcerated people have very few resources” and lack economic and political support, they often turn to alternative methods of protest, he said.

Skarbek described strikes that were similar to that at maximum security that occurred at California’s Pelican Bay State Prison in 2011 and 2013. While the strike in 2011 was ultimately unsuccessful, it led to another protest only two years later that effectively prompted change.

The success of the later protest lies with the number of participants and their solidarity, Skarbek said. There were “too many people for too long that it couldn’t be ignored,” he said, adding that support from “legitimate and influential supporters,” such as Amnesty International, a global human rights organization, also helped bring attention to the issue.

Shepard said that he feels frustrated by maximum security officials’ denial of the hunger strike. Being in prison, “I’m already looked at as someone who is not credible,” he explained.

Alles suggested that one reason the strike was unsuccessful was the lack of media attention it received while it was happening. The prison’s physical walls prevent people from seeing the true conditions on the inside, she added, and officials’ denial is another “wall of silence around what's happening inside the prison.”

Officers in maximum security censor mail and block certain phone numbers, she added, further separating people inside the prison from the outside world. Ventura did not comment on these specific claims.

Shepard said that he wants someone to take accountability for the conditions at maximum security and acknowledge that the prison is primarily a business rather than a rehabilitation center. He also emphasized that the prison system disproportionately affects people of color, whereas correctional officers tend to be white.

For Shepard, there is a distinct “generational incarceration” present in the U.S. that speaks to a greater need to change the rehabilitation system on a national scale.

“I was in jail with my father. People are in here with their fathers and grandfathers and brothers and cousins — constantly, and for generations,” he said. “When? When is that over?”

Correction: A previous version of this story misstated Leonard Jefferson's last name on one mention. The Herald regrets the error.

Elysée is a writer for metro, a producer for the Bruno Brief podcast and an aspiring card game creator. She is a second-year student studying International and Public Affairs on the Policy and Governance Track.