Although the forms of Mariana Ramos Ortiz’s art range from prints and sculptures to interactive pieces, most have one basic material in common — almost everything she creates is made out of sand. The interdisciplinary artist visited Brown Monday night to discuss her most recent work.

Ortiz, who works in both Puerto Rico and Providence, is a 2021 graduate of the Rhode Island School of Design’s MFA program. Currently, some of their pieces are displayed downtown at Central Contemporary Arts and will be on view until Dec. 8. Her work mainly seeks to express the “poetic and formal qualities of sand, and how they reflect the fluctuating landscape in Puerto Rico, both politically and physically,” she said at the event. For Ortiz, this reality has been shaped by a distinct impermanence rooted in centuries of colonialism in Puerto Rico.

Ortiz uses sand as a way to embody this impermanence. It has the potential to “allow viewers to realize there’s a possibility of shifting, of undoing and dismantling the structure,” she explained. Ortiz also uses sand for its ubiquity: “Sand occupies everywhere,” they added.

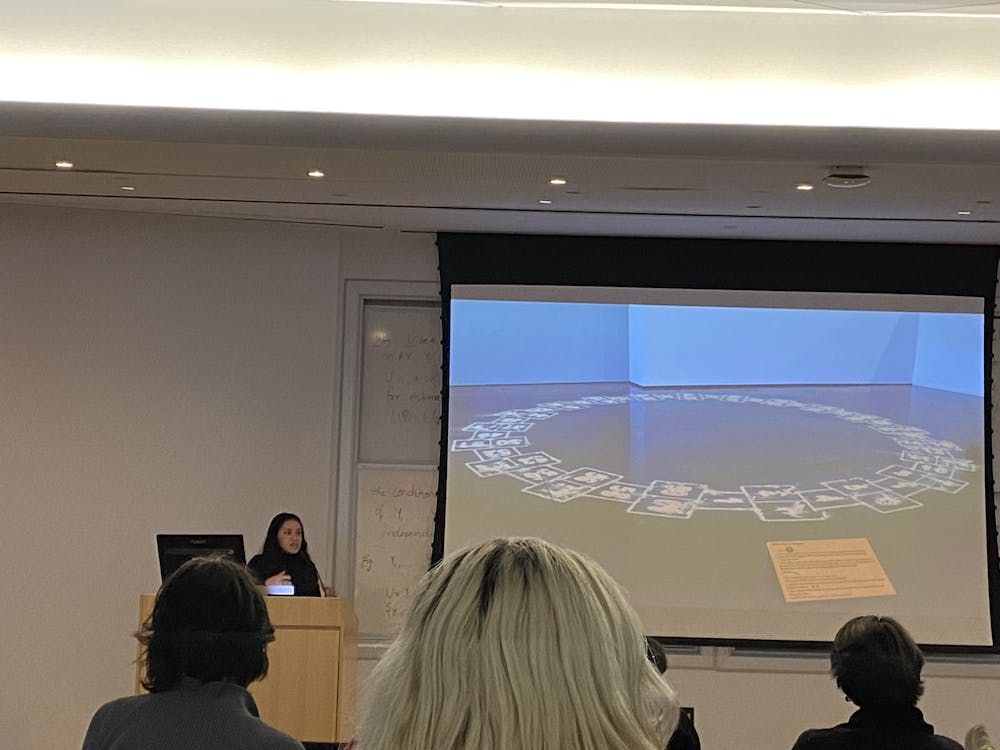

Ortiz takes advantage of these qualities that she finds inherent to sand in pieces such as “La Peregrina,” which translates to hopscotch in some areas of the Caribbean. The piece is a circular version of the game made with stencils and sand. Ortiz considers it an “attempt to consider playful states, fictional action and how they can potentially rebuild relationships, challenge systems at play and then also propose these new realities.” They described the work as “sort of acknowledging the existence of colonial reality but then attempting to challenge those structures.”

Viewers can physically interact with “La Peregrina” by following Ortiz’s instructional booklet to play hopscotch. As more people choose to play, the piece eventually becomes undone, which, as Ortiz explained, is part of why she chose sand as a material.

In regards to all of their work — but especially “La Peregrina” — Ortiz added that they think “people in the U.S. sometimes feel entitled to touch it.” She felt that this was ironic in some ways, for interacting with the art in such a way can be viewed as yet another form of the ongoing U.S. occupation of Puerto Rico and, to a certain extent, of colonialism.

Ortiz also finds an inherent sense of safety in sand due to its relationship to the shore. “A shore is a form of protection, or a buffer to land,” she said. Yet they also pointed out that the shore has historically been a site of incredible susceptibility for colonized communities.

“A lot of invasion that happened in Puerto Rico all happened on the shore,” she said. In this sense, sand is “literally a witness to occupation.”

Recently, Ortiz has been exploring “tormenteras,” which are a type of storm shutter used in Puerto Rico.

“When a storm is coming, usually our neighbors will get together, and younger generations will help older generations set up the heavy tormenteras,” they said. “So there’s this sort of sense of community that I think is intrinsically tied to the idea of feeling protected and safe.”

Ortiz is also interested in ruins, but as a structure of the future, rather than one of the past. She urged the audience to think about “what is speculated by the ruin,” adding that cracks and spaces “can suggest these possible futures that maybe we’re not aware of.”

Ortiz was hosted by Ivan Ramos, assistant professor of theater arts and performance studies, and Leticia Alvarado, associate professor of American and ethnic studies. Ramos commented on the modern relevance of Ortiz’s work. “In the wake of yet another devastating hurricane that had only happened a few weeks before in Puerto Rico, (their work) captures the fragility and resilience of place,” he said.

Ramos also took one of his classes on a field trip to Central Contemporary Arts, allowing his students to experience Ortiz’s work for themselves. Nia Matthews Cox ’26 said that she was “struck by the use of sand as both something that was temporary and permanent” in Ortiz’s work.

Ortiz said she is most intrigued by the crafting of molds, not the structuring of the sand. “Sometimes I’ll spend more time creating the mold than producing the work itself,” they said.

Currently, Ortiz is working on a curatorial project, which she plans to begin displaying next year. Like some of their current work, the exhibition will be centered around “Puerto Rican futurism, speculative-making and world-building as forms of self-determination.” Ortiz added that while the project is still in its initial research stages, she is excited to see where it will end up.

Rya is an Arts & Culture editor from Albany, NY. She is a senior studying English and Literary Arts, and her favorite TV show is Breaking Bad.