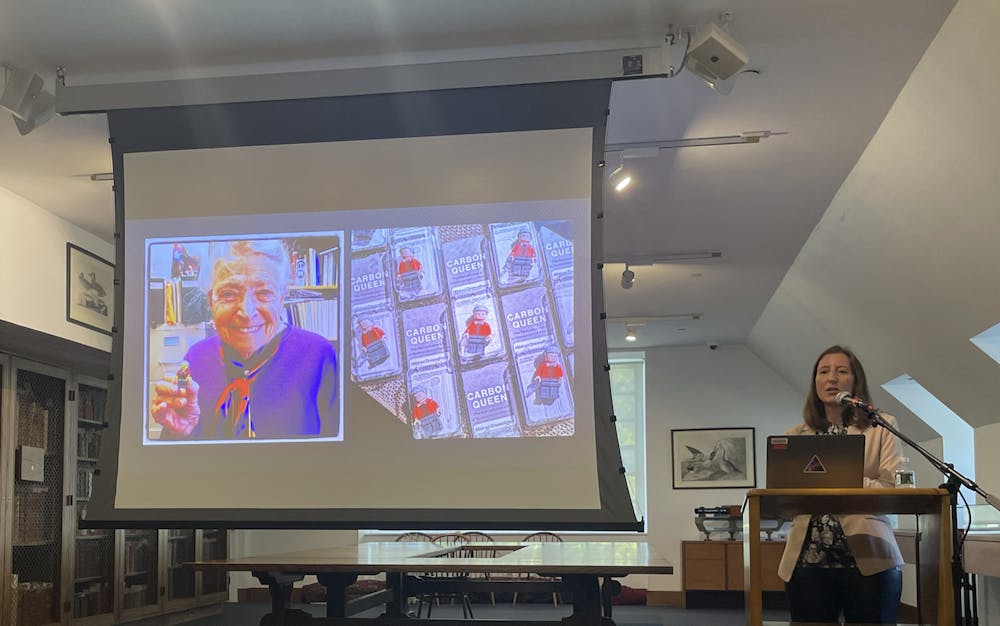

On Ada Lovelace Day — a day to celebrate women in STEM fields — Maia Weinstock ’99, discussed her latest book, “Carbon Queen: The Remarkable Life of Nanoscience Pioneer Mildred Dresselhaus,” elaborating on the life and work of the titular figure before a book signing and reception at the John Hay Library.

Dresselhaus was an “extraordinary physicist and electrical engineer and material scientist,” said Amanda Strauss, associate University librarian for special collections and director of the John Hay Library. “She defied expectations and forged a career in solid state physics, made highly influential discoveries about the properties of carbon and other materials and socially helped reshape our world in countless ways.”

Weinstock first described Dresselhaus’s life, including her journey overcoming poverty and sexism. Dresselhaus was born to immigrant parents during the Great Depression, when her family struggled to put food on the table, Weinstock said. “That was an early lesson for (Dresselhaus) in basically pulling up your bootstraps and making life work no matter what your challenges are.”

After self-studying from books checked out from the New York Public Library, Dresselhaus aced the entrance exam of the one academically-strong high school that was open to girls, Hunter College High School, Weinstock said.

At Hunter College High School, “she became really well known for being a math tutor,” a role that brought in income to help support her family, Weinstock said. Weinstock displayed Dresselhaus’s yearbook photo, next to which is written, “Equations she can solve, any problem she can resolve, Mildred equals wit, brains plus fun, in math and science she's second to none.”

During this time, Dresselhaus crossed paths with Rosalyn Yalow, who was an adjunct professor at Hunter but would go on to win a Nobel Prize in 1977, Weinstock said. Weinstock described how Yalow took Dresselhaus under her wing as a mentor and encouraged her to pursue science as a career.

Yalow warned Dresselhaus about harassment and discrimination as a woman in the field, Weinstock said, but encouraged her to persist, telling her that had what it took to become a scientist.

Dresselhaus worked at Massachusetts Institute of Technology for almost 60 years. She became the institution’s first fully-tenured female professor and the first female president of the American Physical Society, according to Weinstock. She was also awarded the 2012 Kavli Prize in nanoscience "for her pioneering contributions to the study of phonons, electron-phonon interactions and thermal transport in nanostructures,” according to the award website.

One of Dresselhaus’s key contributions to the field was her discovery that changing the placement and configuration of carbon atoms in nanotubes could result in changing the properties of the nanotubes themselves, allowing them to be used in different applications, Weinstock explained. Carbon nanotubes — atoms of carbon shaped as a tube — are used today in a variety of fields, including industrial engineering, sporting goods and the automotive and space industries.

“The number of applications (of carbon nanotubes) has skyrocketed since her career, especially since … the (1980s) and certainly since the early 2000s,” Weinstock said.

Dresselhaus was also “highly influential” in the field of graphene — a single layer of carbon atoms that are arranged as repeating hexagons — Weinstock said. Dresselhaus’s work played a significant role in influencing two Nobel Prize awardees in 2010, whose work focused on experiments on graphene and who mentioned her influence in their speech, Weinstock added.

Dresselhaus received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Barack Obama in 2014. The medal “was for a lifetime of achievement in both her field of solid state physics … but also (for her) great strides in expanding the participation of women and other underrepresented groups in STEM,” Weinstock said.

“I know (Dresselhaus) as a huge figure for women in science,” said Cristina López-Fagundo, a postdoctoral research associate who attended the talk. López-Fagundo, who completed her PhD on graphite, said she frequently cites Dresselhaus’s talks, which is what drew her to the event.

Weinstock graduated from Brown with a concentration in human biology focusing on the evolution of gender. She had originally been interested in pursuing graphic design until she was misplaced during her internship with Scholastic. “I realized that actually I really enjoyed writing and editing science articles for children (during my internship),” she said in an interview with The Herald, explaining her pivot from biology to science journalism.

Strauss, who previously worked with Weinstock on increasing the representation of women in Wikipedia articles, arranged Tuesday’s talk. “This was a wonderful opportunity to showcase both an alum’s work and foreground the History of Science collection at the Hay,” Strauss said.