In the 1960s, the women of Pembroke College were subject to strict rules. They adhered to curfews and conformed to dress codes under the parietal rules enforced at the time.

But in 1965, one doctor in University health services made waves by doing what was unthinkable at the time — prescribing birth control pills to unmarried women.

“Previous to this era, women could not get birth control on campus,” said Pembroke Center Archivist Mary Murphy. “You had to live off campus, and you could, I think, go through campus health care if you were engaged.”

The Herald broke the news Sept. 28, 1965, reporting that Dr. Roswell Johnson said he was prescribing these pills to women over 21 based on “simply my own, private orientation.” He estimated the number of women using pills prescribed by health services as being “very, very, very small” — about one or two.

The Herald additionally published an editorial entitled “A Bitter Pill” praising Johnson’s actions. “Given the realities of the world and of college students, the Health Service’s approach at the women’s college is practical and far-sighted,” the editorial read.

The editorial primarily criticized the then-Pembroke dean for her refusal to admit whether she had sanctioned or had knowledge of the practice of distributing birth control pills, calling this action hypocritical in light of the strict parietal rules to which women were subjected and describing the birth control revelation as “one of the darkest moments in the Pembroke Deanery tenure of Rosemary Pierrel.”

The news that University medical services prescribed birth control to unmarried women was picked up by national media, sparking public outcry.

Johnson had thoroughly considered the cases of the two women who sought birth control, who were both over 21, before prescribing the pill. In a 1989 interview with The Herald, he explained that the initial leak to The Herald came when a 19-year-old woman reporter asked for the pill, and Johnson told her to come back when she was 21.

Johnson explained to reporters at the time of the controversy that he would not have prescribed birth control without parental consent and "a great deal of soul searching."

"I want to feel I'm contributing to a solid relationship and not contributing to unmitigated promiscuity," he said.

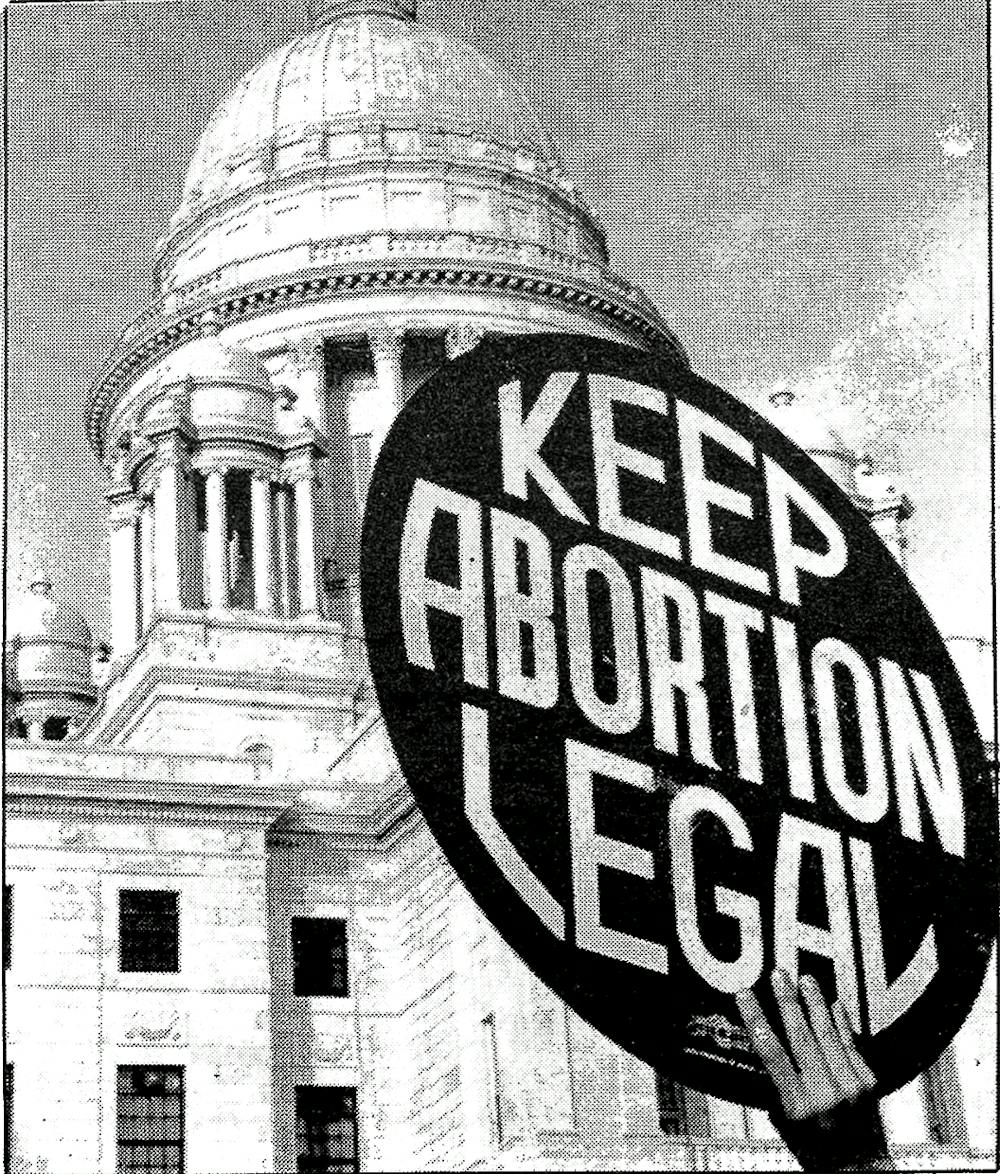

This controversy was the beginning of a long history of discussion, activism and protest around reproductive rights on campus, one that has continued today as students react to and begin activism in response to the overturn of Roe v. Wade’s protection of abortion rights nationwide.

“The first step,” Murphy explained, “was getting access to birth control.”

History of reproductive activism at Brown

Amidst protests regarding issues such as the Open Curriculum, civil rights and the Vietnam War, the second-wave feminist movement also took campus by storm beginning in the early ’70s.

Women of Brown United was the most prominent group fighting for women’s issues and reproductive rights at the time. Mimi Pichey ’72 compiled a history of the organization, which details several efforts specifically around abortion, birth control and sexual politics for women.

The 1970s were “the first time women had gotten out and taken over the streets and started to formulate demands,” Pichey said in a 2015 interview. “This (was) the first time ‘abortion’ … was actually spoken out loud. People did not talk about this; it was whispered.”

“We do have evidence throughout oral histories that women were ‘passing the hat’ or fundraising for each other on their campus floors, so the women could get illegal abortions,” Murphy said.

WBU started an abortion-rights focused subgroup in 1970, which would contribute to the Rhode Island Coalition to Repeal Abortion Laws. Rhode Island’s strong Catholic culture had long contributed to strict anti-abortion legislation, including a requirement that women get death certificates for aborted fetuses.

After Roe v. Wade was decided in 1973, WBU continued its activism, calling for a change in Rhode Island’s abortion laws. In the years to follow, WBU also “established a service to escort patients seeking abortions (to) safely enter the Women’s Medical Center through groups of anti-abortion protesters,” according to Pichey’s history.

The Sarah Doyle Center opened in 1975 and was also a resource for students on campus.

“Our center’s early history is rooted in student activism and particularly the feminist movement, which prioritized reproductive health care and advocacy alongside other issues of gender equity,” said Felicia Salinas-Moniz MA'06 PhD'13, director of the Sarah Doyle Center for Women and Gender.

“Its founding was largely due to the efforts of Women of Brown United, a women's liberation group on campus who first drafted the proposal for a center and through the working group on the Status of Women at Brown, which included 45 faculty, staff, alumni, graduate and undergraduate students who met to discuss the center's formation,” she said.

The Herald reported on WBU’s escort service Feb. 14, 1986, when student members walked with abortion patients from their cars to the clinic. “Six anti-abortionists gathered around the sedan, screaming at the woman inside. Two Brown students approached, green sashes across their coats, and helped the woman out of her car,” The Herald reported.

While activism in favor of abortion continued throughout the 1980s and ’90s, anti-abortion work also gained some visibility on campus. In the early 2000s, Students for Life emphasized that beyond abortion, they also took stances on the death penalty and euthenasia in line with their values.

The bigger picture: the Dobbs decision

Many academics and activists agreed that the overturn of Roe was long in the making.

“I think that the dismantling of Roe is something that has been happening for decades with the federal adoption of the Hyde Amendment in 1977, which prohibited the use of federal funds for abortion except for when a pregnant person's life was at stake,” said Salinas-Moniz. Abortion restrictions based on state legislations also created barriers both for people in need of services and for providers, she continued.

Sarah Williams, visiting assistant professor of anthropology and gender studies, explained that legally, Roe was not a strong protection of abortion rights to begin with.

“It was what some scholars have called a negative right — you don't have the right to have an abortion, you have the right for the government not to intervene in that decision,” she explained.

“Looking at women's history, this has been a project in the making of the far right and the United States for 50 years. It's part of a larger project, to divide citizens through the control of women's bodies,” Murphy said.

The fall of Roe and the Dobbs decision has led to a “pulling apart of the state's long neo-confederate lines,” she added. “Women have always been used as tools of war, and we see that here within our own country.”

Hannah Fernandez ’23, a member of the e-board for Planned Parenthood Advocates at Brown, said that despite anticipating the overturn of Roe when the draft opinion was leaked, it still felt like a gut-punch.

“It was really just so overwhelming for me that I had to take space from social media,” she said.

She added that reproductive healthcare extends well beyond abortion rights amid threats to other reproductive rights and national efforts to roll back other facets of healthcare.

Kyle Nunes ’24, vice president of Students for Life, described a different reaction to the Dobbs decision. “We're definitely thrilled about the decision,” he said. “I think it's probably … the opposite way for most Brown students.”

“I'm hoping that we'll look back in 50 years, maybe, and say, ‘boy, we had that wrong for a while, and that's that was a shameful period in our history, where we were okay with ending the life of an unborn child,’” Nunes added.

Activism, reproductive justice and the future

While the Reproductive Privacy Act, which protects abortion rights in Rhode Island, was passed in 2019, people with all political viewpoints remain attuned to this issue and what the future will look like.

Fernandez explained that members of Planned Parenthood Advocates continue to volunteer at clinics and bring visibility to the issue in addition to supporting specific state legislation.

“There's a bill that's come up a couple times in the Rhode Island State House that still hasn't been passed yet called the Equality in Abortion Coverage Act,” Fernandez said. “What that would do is that would expand state funded insurance to also cover abortion and a lot of other maternal health care.”

The Womxn Project, formed in 2016, advocated for the RPA and now advocates for the Equality in Abortion Coverage Act.

“We protected the right for people to have abortions, and those are predominantly folks who have private insurance,” said Jocelyn Foye, co-founder and executive director of The Womxn Project. “Now what does it look like for the people who need it across the board?”

Pro-choice advocates said they were determined to gain momentum and start looking beyond just abortion rights.

Nunes explained that he hopes Students for Life will take a more holistic approach to its message and outreach. “If a woman's going into this feeling like (abortion) is her only option, and she really can't support a child, we should focus on that, too,” he said. “How can we help her to the point where she feels like she could?”

Nunes added that the club will attend a pro-life conference in the coming months and attend the March for Life. “It's not the case that just because we don't support abortion, we don't support women or don't care about women. We care a lot,” he said. “People will go to the clinics and just scream at people, and it's not good. But we're not all like that.”

For Foye, the issue extends well beyond abortion itself. “It's not just about a medical procedure. It's about bodily safety and dignity and people being able to choose when they're ready to have a family,” she said.

Williams explained that reproductive justice, as opposed to other feminist or reproductive movements, has a greater focus on racial, class and other forms of social justice in addition to advocating for reproductive rights.

“Reproductive justice reminds us that reproductive rights (and) reproductive health (are) not possible if you're not also working towards equality and equity in other areas as well,” she explained.

Fernandez also emphasized the need for a bigger picture view of abortion and birth control, especially as people everywhere, including at the University, still need access to reproductive care. “People always try to say that public health is not political and medicine is separate from politics,” she said. “But at this point in the way that things have devolved, everything is politics — public health is politics.”

Williams added that we can learn from other countries and cultures about how to manage reproductive healthcare.

“In Mexico, there are very deep and long-standing abortion networks,” she said. “Up to about 12 weeks of pregnancy, you can do a medication abortion with misoprostol and mifepristone.”

These underground networks “are really about community members who educate themselves about self-managed abortion and then become a phone number or text line or something that a pregnant person can contact,” Williams explained. “They send the pills and then are there as a friend, a guide, either sometimes in person, often over the phone or text, guiding them through the abortion.”

Fernandez emphasized that the fight continues, and that she hopes for larger change in the future.

“There are so many people who are so passionate about these issues, and who are literally raising hell,” she said. “Real structural change is our best option.”

Katy Pickens was the managing editor of newsroom and vice president of The Brown Daily Herald's 133rd Editorial Board. She previously served as a Metro section editor covering College Hill, Fox Point and the Jewelry District, housing & campus footprint and activism, all while maintaining a passion for knitting tiny hats.