The growing popularity of the creative writing degree over the last 50 years has come with a growing critique of the institutionalization of writing. This discourse has often circled back to the same question: Can writing be taught?

Although there never has been and likely never will be a conclusive answer to this question, the practice of teaching writing has continued despite the debate. But, very often, it is those who write that teach. The Department in Literary Arts at Brown has had a faculty of nationally and internationally renowned authors since its establishment in the 1960s by poet, translator, critic and Professor Emeritus of English and comparative literature Edwin Honig.

You can teach writing, said Associate Professor of Literary Arts Karan Mahajan, even if you can’t make someone talented who isn’t talented.

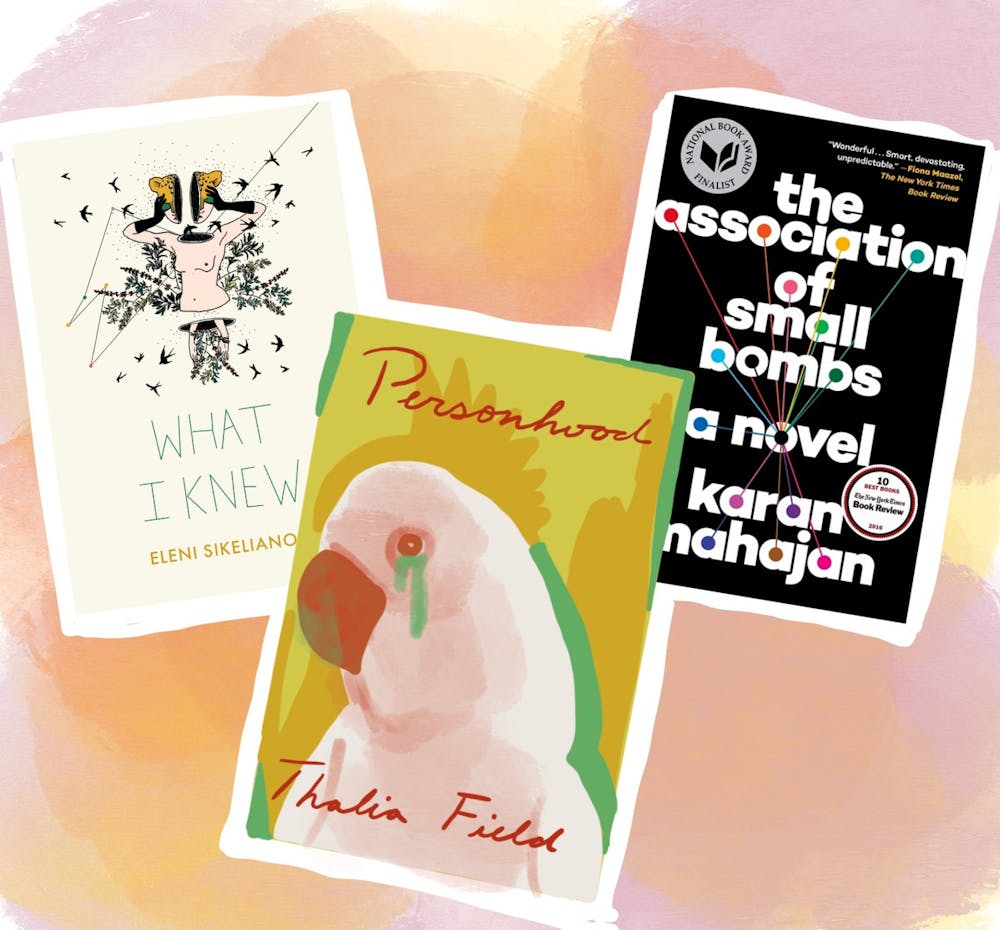

Author of “Family Planning” and “The Association of Small Bombs,” a finalist for the 2016 National Book Awards, Mahajan tries to locate the strengths of the writer and encourage them in that direction. “I think you can teach students to access the most interesting parts of themselves and to show them that they carry within them the germs of interesting stories,” he said.

Professor of Literary Arts Thalia Field ’88 MFA’95 feels “very strongly that creative writing can be taught” but disagrees pedagogically with the standard “workshop model,” she said. Field is the author of several innovative and experimental books, the most recent of which is “Personhood,” published in 2021.

The workshop format “conflates teaching with editing,” she said, “and it ignores (the) creative process, which to me is at the heart of learning how to be a sustainably productive and healthy artist in the world.”

“I see a lot of paralysis and a lot of young artists getting stuck in their practice, because creative process is not at the heart of the pedagogy in most creative writing workshops,” Field said. She believes that most people need coaching and support until they begin to learn their own creative process.

Field also teaches very interdisciplinarily so writers in her classes can engage with multiple forms. Her teaching style mirrors her writing practice and her experimental work, she explained.

“I've always worked at the intersection of creative nonfiction and more imaginative writing,” she said. “I find a very important place where the two can create opportunities to think through questions that are difficult to do in any other way.”

The experimental nature of her work was one of the many reasons Field decided to teach in addition to writing. “I didn’t want to put the pressure on my books to have to make money in that way,” she said. But she has also always been interested in “the dynamics of pedagogy” and began teaching in different forms soon after college.

Professor of Literary Arts Eleni Sikelianos is the author of two hybrid memoirs and several poems, collections and chapbooks, including a book-length poem, “What I Knew,” published in 2019. Her own research as an artist has influenced what she teaches, she said.

“Poetry for me in particular is an impulse toward freedom, and that can be freedom from syntax, freedom from the ways that we expect language to make meaning — it can mean all kinds of freedom,” Sikelianos added. “That's something that I always want to think about when I'm teaching: How can I help my students feel liberated in various ways, and how can we have adventures together?”

Mahajan also likes talking to students about what it’s “actually like to be a writer,” he said, which involves looking at the lives of writers and considering not only how they came into the profession but also how they sustain it.

For many literary arts professors, the practice of teaching impacts the art of writing just as writing influences teaching.

Teaching has made Mahajan a better writer by virtue of making him a better reader and thinker, he said. As a professor, he has to carefully reread books he has read before, which helps him extract new value from them.

“And your students show you new ways of looking at these texts,” he added.

Since writing is a solitary practice, he likes the balance of having time to himself and meeting with students. “I’m always energized when I come out of one of my classes,” he added.

“I’m learning from my students all the time, as well as the texts we’re reading together,” Sikelianos said. Her past students have also frequently become collaborators after she taught them.

But she also acknowledged that teaching can inhibit her writing in some ways. “You’re trying to put frames on ways of thinking to be able to hand it over to others,” Sikelianos said. These frameworks may not be the most fruitful approach for her own writing. The time constraints pose an additional challenge, she added.

Field is currently on leave to focus on her own work. “It requires having time when I am not teaching in order to really do the deeper, more dream-like, more research-based aspects of the process,” Field said. “There are parts of my creative process that are easier to do while I'm teaching and parts that are really impossible.”

Still, Field finds teaching to be very inspiring. “I love working with students and young artists, and so it doesn't harm me in any way,” she said.

The professors also had words of advice for aspiring writers and students of literary arts.

“I think the people who become writers are people who keep doing it, who are willing to take risks with their writing, who are willing to tell the truth about things that are difficult to talk about otherwise,” Mahajan said.

But he stressed that writing is not for everyone — it is a difficult and lonely profession which might make some people unhappy in the long run. “I think there’s a kind of romance associated with writing that I think it’s our duty as professors to dispel and to expose students to the difficulties that you experience in a career as a writer,” he said.

Field emphasized the importance of deepening the relationship a writer has with their own work so it remains “genuine, authentic, radical and unique.” “The relationship with your work is a primary, evolving, dynamic relationship, and it's not always easy and it's not always linear,” she said.

Sikelianos, on the other hand, spoke of the importance of finding a community of other writers. “That doesn't have to be a living community,” she said. “It can be a community of poets and writers who died centuries ago. But it's finding those things that inspire you.”