On Friday, the Bell and Cohen Galleries unveiled the traveling exhibition “Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration,” which features artists who have either been or are incarcerated, as well as those whose work aims to shed light on the realities of incarceration.

A panel kicked off the exhibition featuring artists Jared Owens, Mark Loughney and Mary Enoch Elizabeth Baxter. Nicole Fleetwood, curator and professor of media, culture and communication at New York University, moderated. The exhibition was hosted by the Brown Arts Institute in collaboration with the Department of Africana Studies and Rites and Reason Theatre.

Owens is a self-taught, multi-disciplinary artist who spent more than 18 years of his life in prison. His works range from portraits and shadow boxes to mixed-media pieces, all of which involve what he called a “practice of discovery.”

The process is about “discovering new ways to express what I experienced inside of prison,” Owens said during the panel. “I’m constantly looking for threads — narrow threads — that I stitch together inside the works.”

One of Owens’s pieces on display, entitled “Ellapsium: master & Helm,” superimposes a slave ship over a federal prison. The piece spans three large panels and emphasizes that slavery, though technically an abolished instutition, permeates through contemporary mass incarceration.

“We take for granted that people who are locked up are sustenance for a whole legal system,” Owens said. He explained that the profit received by courts and the criminal justice system from mass incarceration often goes overlooked.

Baxter, a Philadelphia-based film, music and visual artist whose work pays special attention to the plight of incarcerated women of color, discussed her work next. She has been out of prison for more than a decade and has since confronted incarceration through both her art and her involvement in public policy.

Baxter elaborated on her work as an activist. Since the beginning of mass incarceration in the U.S., “issues that particularly pertain to women — pregnancy, and things of that nature — weren’t really thought about,” she said.

To better advocate for these historically neglected perspectives, Baxter co-founded the Dignity Act Now Collective. The collective’s mission is “art activism,” particularly pertaining to incarcerated Black women, trans and non-binary people, she said.

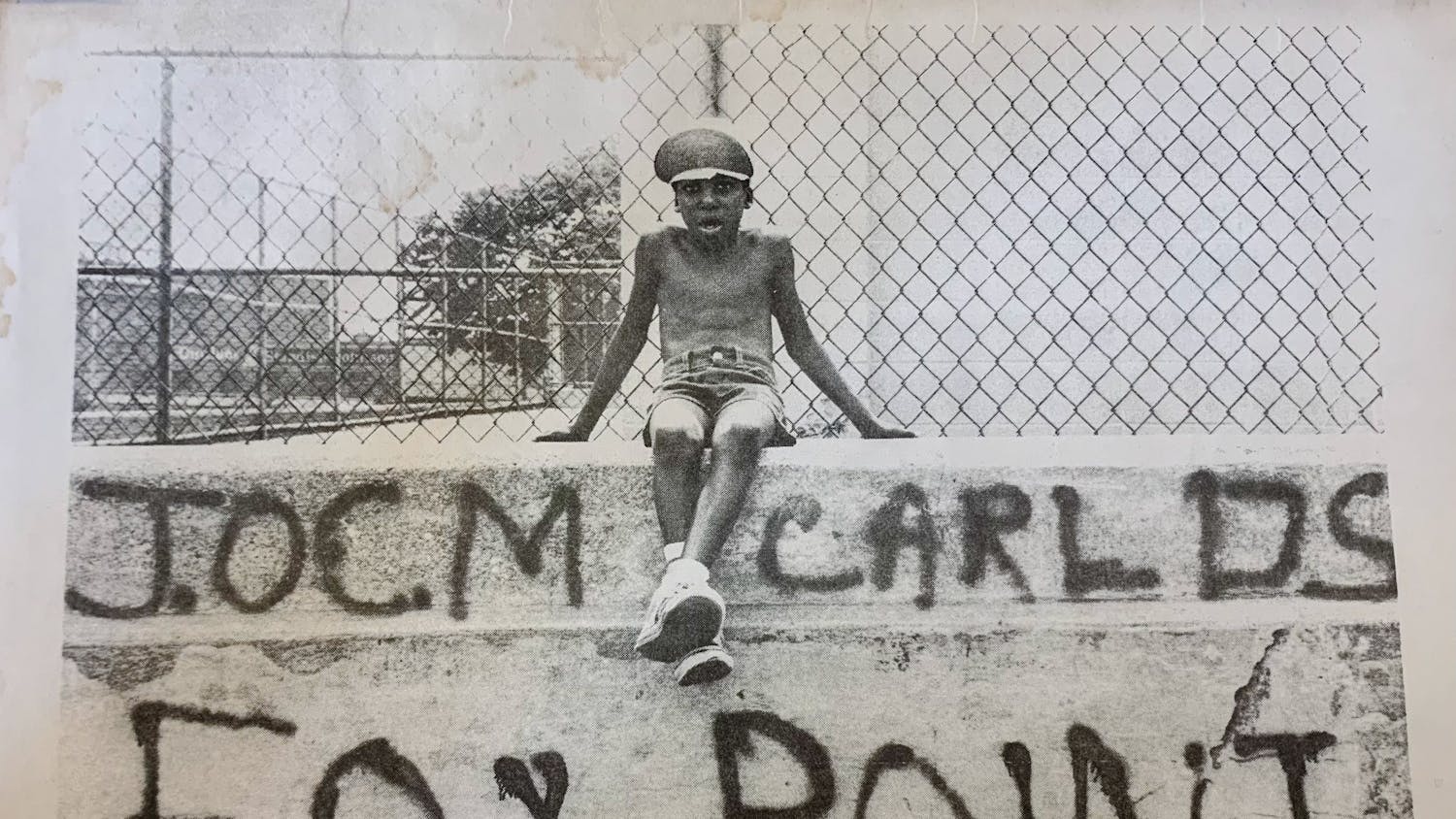

One of Baxter’s pieces on display seeks to challenge the “adultification bias” of young Black girls, or the racist perception that Black girls mature faster than other youth. After discovering pornographic images taken by Thomas Eakins in 1882 — which were available in the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts’s digital collections until summer 2021 — she superimposed herself on these photos. Although the resulting counter-narrative piece, entitled “Consecration to Mary,” prompted PAFA to remove the photos from their online database, it never issued a public apology for displaying them.

Mark Loughney was last to introduce himself. Having been released only a few months ago, Loughney completed all of his displayed work in prison.

Loughney’s art consists mainly of drawings and paintings with an emphasis on portraiture. “Most of my work reflects, in one way or another, the stagnating and regimentation of bodies and figures in space,” he said.

He also stressed the importance of incorporating absurdity into some of his pieces. “You have to be real flexible with your sanity,” he said, referring to the ten years he spent in a Pennsylvania prison. “If you’re too rigid with your grasp on reality, you’re gonna shatter.”

What Loughney considers his “magnum opus” occupies an entire wall of the Bell Gallery. The project, entitled “Pyrrhic Defeat,” consists entirely of portraits of incarcerated individuals, all done in pencil on nine-by-12-inch pieces of paper. Each took only 15 to 20 minutes to complete.

After each artist was given a chance to speak, the conversation turned towards a Q and A with the audience.

“Being an artist is, like, the craziest thing you can decide to do when you come home from prison,” Owens said. All three artists stressed the incredible support the people behind “Marking Time” and other projects have offered them.

Owens, Baxter and Loughney alike noted their work aims to illuminate the unjust realities and consequences of mass incarceration to elicit understanding and action.

Baxter explained that her goal when teaching is to show students “mainly how to use art, how to reimagine your own stories to empower yourself to rewrite a different narrative.”

“A big part of (the work) is humanizing people who are mass-incarcerated, and taking the stigma off of them,” Owens said.

Loughney emphasized the importance of discourse within art related to mass incarceration and systemic racism. He described a pair of chairs he had passed on campus earlier that day. “That’s kind of all we can hope to do, is to place two chairs and open a discussion,” he explained. “So that’s what I feel like I’m doing — I’m putting those chairs out there.”

The exhibition will remain on display until Dec. 18.

Rya is an arts & culture section editor from Albany, NY. She is a junior studying English and Literary Arts, and her favorite TV show is Breaking Bad.