A team of University researchers is testing the use of noninvasive low-intensity ultrasound to treat mental health disorders such as depression and anxiety.

Funded by the National Institutes of Health, this five year study at the Providence Veterans Affairs Medical Center is a first-in-human study, meaning that this treatment is being tested for the first time ever in a patient population.

Noninvasive brain stimulation techniques use targeted radiation to alter the activity of the brain from the outside of the skull, said Noah Philip, professor of psychiatry and human behavior and principal investigator.

Although existing noninvasive brain stimulation techniques can be used to treat psychiatric disorders such as anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder, they are limited by their inability to target specific brain regions, Philip added.

“In a lot of psychiatric disorders, there are a variety of different brain structures involved in maintaining and promoting illness,” said Amanda Arulpragasam, a postdoctoral researcher in Philip’s lab. But current techniques only allow researchers to target the cerebral cortex, which can then impact other parts of the brain, she added.

With this new ultrasound technology, the researchers are hoping to directly modulate areas of the brain implicated in psychiatric disorders, Arulpragasam said.

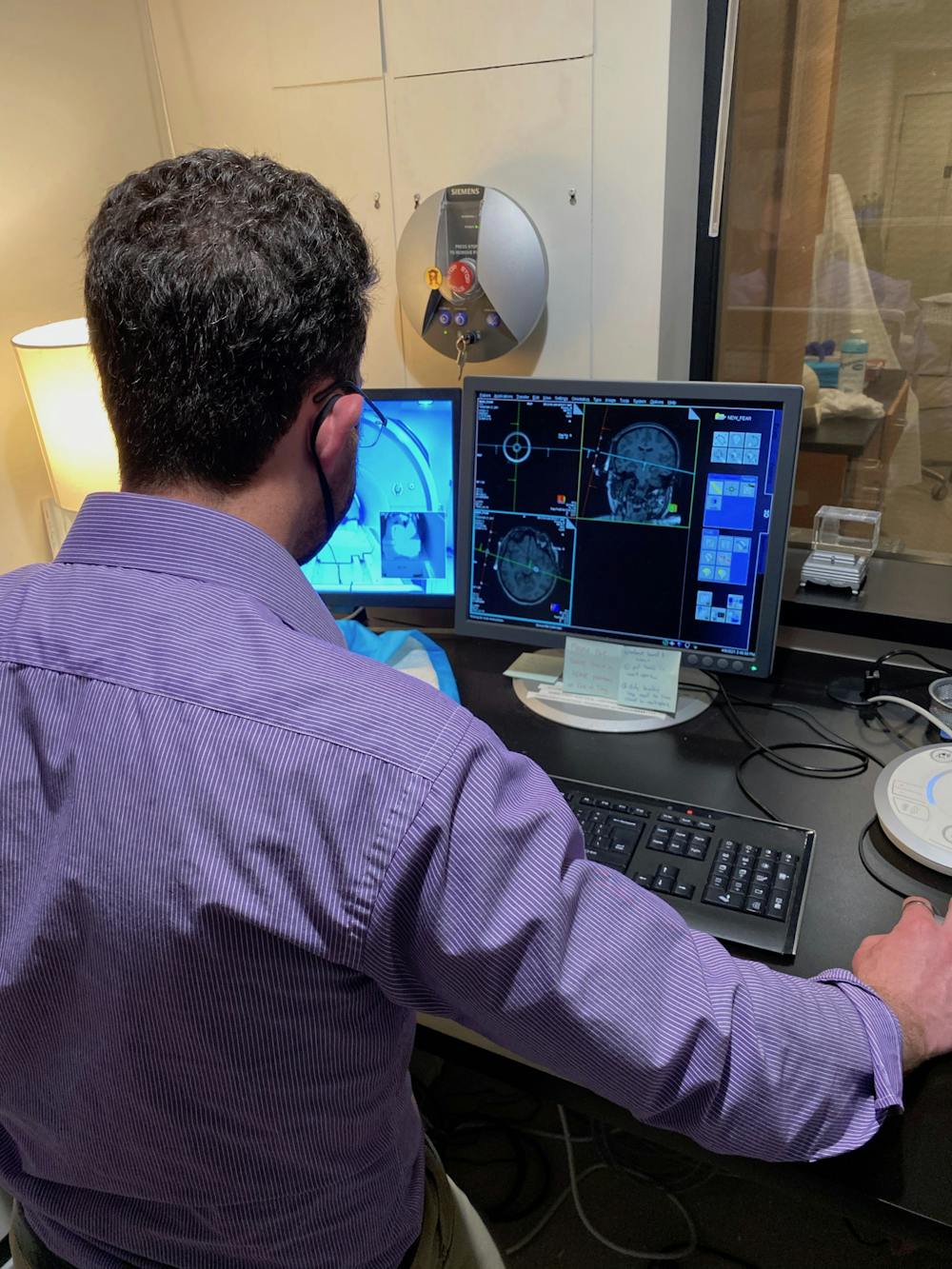

A device called a transducer emits low-intensity ultrasound waves that converge at a specific focal point, similar to how a magnifying glass causes light waves to converge, explained Mascha van 't Wout, associate professor of psychiatry and human behavior. Using MRI technology, the researchers can visualize the patient’s internal brain structure and position the transducer so that the focal point is located on the structure they want to modulate.

Ideally, these low-intensity ultrasound waves decrease the activity of the desired brain region without affecting nearby areas, she added.

For this study, Philip and his team are targeting the amygdala, a region deep in the brain that detects fearful and threatening stimuli and activates the body’s fight or flight system. Overactivity of the amygdala is believed to contribute to symptoms of anxiety, depression and PTSD by increasing perception of negative stimuli, Philip said.

The researchers use functional MRI to track changes in brain activity while the ultrasound is being administered, said Christina Faucher ’19, who began her research in Philip’s lab as an undergraduate and is now a staff researcher. Study participants also undergo regular neuropsychological assessments to make sure their cognitive processes like memory and learning are not affected, and that the treatment isn’t worsening their psychological symptoms.

“Since this is a first-in-human style study, our main aims are to test for safety and tolerability,” Arulpragasam said. “So we’re making sure that this device isn’t causing any major side effects for our participants, and that it is engaging this target area and actually modulating the amygdala like we want it to.”

Although the study is ongoing, Philip said that the initial results are promising.

“What we have seen is that the ultrasound is modulating the amygdala,” Philip said. “And if you look even a couple of millimeters away from where the ultrasound beam is going, there's no effect. So it really is working at the millimeter precision level that we want it to be working.”

He added that the scientists have not observed any clinical side effects.

The researchers plan to publish their initial findings in a case report at some point later this year.

Ultimately, the goal is to “broaden the toolbox” clinicians can use to treat psychiatric illness, said Faucher. “We see a lot of patients who have a relapse of symptoms, or who continue to have some degree of symptoms, despite existing treatments. … We’re finding new ways and new tools that we can offer to patients, either in addition to or in lieu of prior treatments.”

“Every doctor's office in this country has an ultrasound device,” Philip said. And unlike many other technology-based interventions in psychiatry, “This is a technology that's very portable, very scalable and has the potential to be easily deployed to … places that have a difficult time accessing other ways to treat psychiatric illness.”

The technology would also provide researchers with a new noninvasive tool to study how different areas of the brain respond to modulation, with implications for both basic science research and researchers developing treatments for neurological diseases.

“The potential and the excitement around this technology is very, very high,” Philip said. “If we can show that this technology is safe, … it opens up just a tremendous floodgate of opportunities for patients and for further brain-based research.”